Camilo Mejia is enjoying civilian life. He recently moved to a modest house in North Miami that he will share with his 7-year-old daughter, Samantha. He’s still working on furnishing and stocking the new home; the living room is empty other than two lounge chairs, wine glasses are used for water, and once the cable installation guys leave, he’ll have some entertainment. He says he chose this house because it is close to where Samantha lives with her mother, Camilo’s mother and stepfather’s home.

Mejia, 32, stands in his backyard dressed in cargo shorts, a loose-fitting white shirt and flip-flops; perfect for mid-January Miami weather. The garden is ample and green, reminiscent of Mejia’s native Nicaragua. Here, he’ll be able to enjoy raising Samantha, work on the many books he is looking forward to writing and continue his education and efforts as a peace activist.

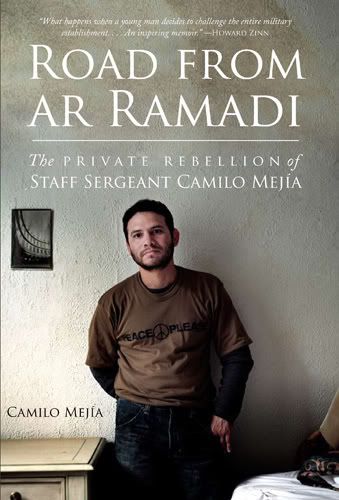

His first book, a memoir entitled, “The Road from Ar Ramadi: The Private Rebellion of Staff Sergeant Camilo Mejia,” reveals his life and long journey to his current state of peace.

“I actually thought he was the surfer type when I first met him,” said Mejia’s landlord, Sean Woods. “He has that sort of laid back attitude.” It was that same attitude that led Woods to sell the house to Mejia.

“He seemed like a smart guy, very calm and reserved,” said Woods. “Just by talking to him you can tell that he is a very honest and trustworthy person.”

In his young life, Mejia has endured many obstacles to find peace. His awesome story takes place in four countries, where his life experiences have molded him into who he is today.

Mejia was born in Managua, Nicaragua in 1975, a few years prior to the triumph of the Sandinista revolution over the repressive Somoza regime. His mother is from Costa Rica and his father, Carlos Mejia-Godoy, is a famous folk singer from Nicaragua whose activist songs garnered international attention. His parents were both committed to the resistance against Somoza’s regime, before and during the Sandinista triumph. This allowed Mejia and his brother, Carlos, to enjoy a cushy lifestyle in Costa Rica and Nicaragua.

“I grew up a pretty shallow kid, I didn’t question where things came from,” said Mejia. “But I did absorb what was happening at the time.”

At 18, Mejia moved to the United States. After living in luxury in Nicaragua for most of his childhood, Mejia had to work at a fast-food restaurant while finishing high school in Florida. After graduating, Mejia attended a community college until he ran out of money. That is what led him to enlist in the army.

“The military seemed to offer that sense of belonging. It seemed like a good way to make friends, to be a part of society. It was something that I needed,” he said, adding that isolation also influenced his decision to join the military.

Mejia spent three-and-a-half years in active duty, mostly in Georgia and Texas. He said his time in the army wasn’t difficult to adjust to because of his nomadic lifestyle prior to enlisting.

Mejia excelled in the army. He easily made friends and won conduct awards.

After completing what he thought was the end of his contract, Mejia found he had actually enlisted for eight years, not three. He decided to finish his duty with the Florida National Guard while going to school.

In the National Guard, he lived more as a civilian than a soldier. Mejia said the expectations were the same, and going out on missions and training often conflicted with his personal life. As a result, he missed Samantha’s first and second birthdays. During this time, Mejia began feeling disillusioned with the military.

“I started to realize, for the first time, that the military acts as if they own you and you don’t have rights,” he said, adding the National Guard was just as bad. He was motivated that his contract with the military would end soon and he was completing a bachelor’s degree in psychology. “Or so I thought,” said Mejia. In early 2003, a few months before graduation and the end of his contract, his unit was called to Iraq.

“It was pretty difficult to think that your whole plan, your whole idea of who you are going to be, where you are going in life is shattered, crumbled, right before your eyes,” he said.

As he wrote in his book, Mejia witnessed atrocities during his five-month stint in Iraq. Torture and abuse of prisoners and civilians and lack of proper protection of his men on, what he calls, “senseless missions” were some of the issues Mejia had problems with.

“There is no one word that can encompass everything I saw,” said Mejia. “It was very unpredictable?it was a constant guessing game.”

From the beginning, Mejia used his immigrant status to avoid going to Iraq (legal residents who haven’t applied for citizenship can only serve a total of eight years in the military) and was finally allowed a two-week leave of absence to fix legal matters back at home. He never returned to Iraq.

Although he went through a period of inner conflict before making his ultimate decision, one that disappointed and angered members of his squad, Mejia felt it was something he had to do.

“I had to step outside of that (criticism) and make my own decision,” said Mejia.

Knowing the consequences of desertion, Mejia went into hiding for five months in New York. He gave several clandestine interviews with media outlets about the situation in Iraq, worked with organizations like Citizen Soldier to prepare his eventual surrender and inevitable desertion case and began writing his conscientious objector claim.

“That time helped me understand and articulate my experience in Iraq,” he said. “It was crucial in my preparation for surrender and dealing with my fear.”

Finally, on March 15, 2004, Mejia surrendered to the military. He was no longer afraid.

“I understood that it was something I had to do in order to live with myself and that what happened to me would not be that bad.”

During the three day trial that started about a month later, Mejia’s defense team was not allowed to bring up what they thought were the real issues of the case: the legality of the war, his conscientious objector and immigrant status; they were limited to painting Mejia as a good soldier who made a bad decision.

In the end, Mejia was found guilty of desertion. His sentence included a bad conduct discharge from the military and a year in prison. Instead of feeling trapped while in prison, Mejia said he felt free. He has no animosity or regrets about his decision.

“Going through everything I went through made me who I am,” Mejia said. “It has become a tool for activism and gave me this platform to be able to speak out and create awareness.”

The nine months he served in jail “(were) very peaceful for me,” he said. “For a long time I had not had any time to think or to be with myself, or to read.”

Since his released from prison, Mejia is appealing his bad conduct dismissal and continues waiting on his conscientious objector status, hoping it will help others in similar situations.

While in prison, Mejia was visited by Daniel Ellsberg, the infamous leak of the Pentagon Papers, to join a budding organization, Iraq Veterans against the War. He is now the chair of the organization.

“I’m glad that Camilo was put in that position because he has extraordinary leadership,” said Jabbar Magruder, co-chair of IVAW and president of the organization’s Los Angeles chapter. “Some people are best suited for certain things, and Camilo has great vision.”

Despite being on opposite sides of the country, Mejia and Magruder keep in close contact to maintain consensus among other board members.

“I know that all I have to do is pick up the phone and Camilo’s going to be on the other end, and that is very refreshing,” said Magruder, who is a biomedical physics major at CSUN.

Mejia travels all over the country for IVAW and works with other organizations like Vet

erans for Peace.

“He is very focused when he does work with IVAW, even though he is involved with other groups,” said Magruder.

With only one semester left to receive his bachelor’s degree, Mejia went back to school and finished college at 27. Though he became disillusioned with the educational system while in the military, Mejia now plans on studying political science instead of continuing in the field of psychology, but vows he has no interest in going becoming a politician.

Mejia is currently working on a second memoir about his jail experience and wants to delve into the genre of fiction writing.

Although he hasn’t actually read the final copy of his book, he says the writing was cathartic. “Having to get all those things to the surface and putting them on paper was a very positive thing,” says Mejia. “It helped a great deal in my healing process.”

This also included rebuilding his relationship with his daughter, who now stays with him every other weekend. Mejia was afraid his time in Iraq would affect his ability to raise Samantha, but today he sees it as a learning experience for both of them.

“It takes strength to be the daughter of a war resister,” he said.

*Photo courtesy of The New Press

*Photo courtesy of The New Press

“The recruiter didn’t really have to work hard to get me to sign the treacherous contract?My visit to the recruiters’ office wasn’t to decide whether I wanted to join, but to decide what military branch and specialty I would choose, which turned out to be the army’s infantry.”

“My feelings about the military had changed radically by the end of 2002? I knew the lifestyle, the food, the mentality, the discipline, even the sense of humor. But I was disappointed in the system. It preyed on the vulnerability of people, exploiting their lack of options to get them to sign up, and subsequently tied them into service with the constant promise of benefits that were just around the corner.”

“Looking across this magnificent landscape, I reflected on the contrast between the beauty of the country and the convulsive violence we were meeting every day. It saddened me. Not for the first time I felt a connection with the Iraqi people. I had already seen the pain and suffering in their eyes too often for comfort. I wanted to help them rebuild their crumbled ancient nation, bombed-out remains of a biblical land. If only we could bring peace to these people, not as foreign soldiers, but as fellow human beings, as citizens without borders.”

“After thinking I was about to get out of the army and the war, a sense of impotence took possession of my inner self. How could it be? I had to go back to Iraq, brutalize the people, rape the land, and possibly die there, all against my conscience? I had to find a way not to lose myself in the war, to return home still human so I could be a father to my daughter.”

“This would be, first and foremost, a war waged, within myself, one where my fears and doubts would come face to face with my conscience, a war to reclaim my humanity and my spiritual freedom. It would also be a war against the system I had come from, a battle against the military machine, the imperial dragon that devours its own soldiers and Iraqi civilians alike for the sake of profits. I knew that somehow I had to turn my words into weapons, that speaking out was now my only way to fight.”

“Yet the maneuverings and tricks of the military in the two months between my surrender and my trial would pale in comparison to the blatant violation of its own regulations that occurred during the trial itself. I had figured the military penal code was highly biased, but the injustice I would witness in the three days of my court-martial proved to go beyond anything I had ever imagined.”

“Though I was handcuffed as I walked down the steps of the courthouse to the police vehicle, that was the moment that I gained my freedom. I understood then that freedom is not something physical, but a condition of the mind and of the heart. On that day I learned that there is no greater freedom than the freedom to follow one’s conscience. That say I was free, in a way I had never been before.”