Op-Ed: Why Does California Need AB-1460 (Ethnic Studies Requirement)?

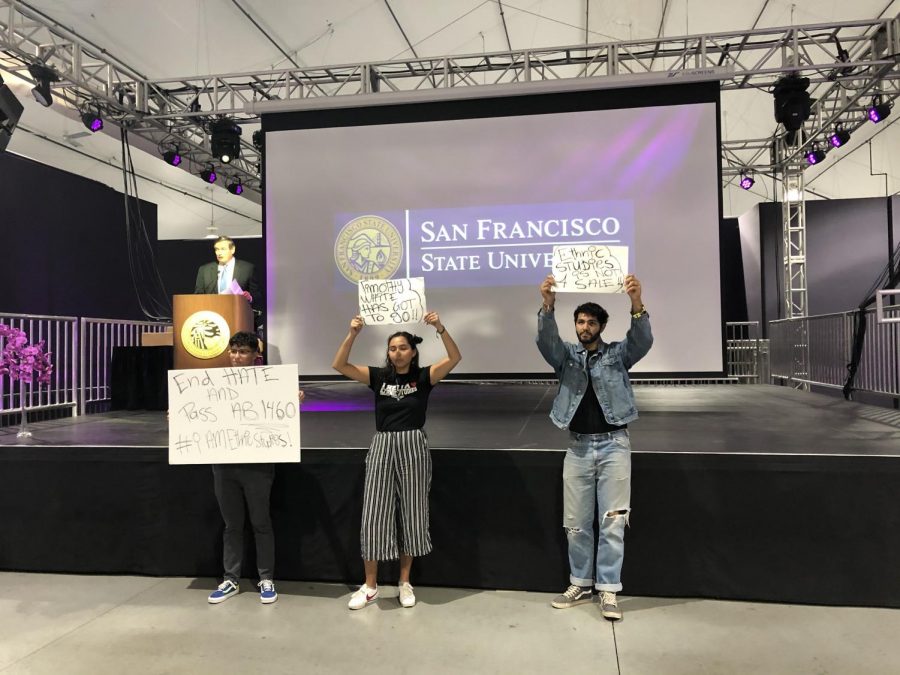

Courtesy of Stevie Ruiz

Students protest against CSU Chancellor Timothy White at the 50th Anniversary of Ethnic Studies at SFSU in 2019.

July 8, 2020

When the California State Senate voted in favor (30-5) of Assemblymember Shirley Weber’s bill AB-1460 — a state law that will require every California State University (CSU) undergraduate to take an Ethnic Studies course in Black Studies, Chicanx/Latinx Studies, Asian American Studies, or American Indian Studies, I was ecstatic because it was one step to put the CSU on the path to redress racial inequity.

The CSU is the largest public serving institution with the largest achievement gap between white students and Black, Latinx, American Indian, and low-income students. Countless studies have proven Ethnic Studies puts students on the path towards graduation, while at the same time it redresses the pain, grief, and suffering that students experience due to poverty, criminalization, war, and houselesness.

Ethnic Studies taps into the cultural and historical knowledge that all students come into university with in order to energize their interests about race relations, class inequity, and social justice. One obstacle that faculty and students have encountered has come from one administrative office: CSU Office of the Chancellor.

When it came to support for AB-1460, Ethnic Studies faculty and students knew Chancellor Timothy White’s Office would try to kill the bill. In each subcommittee hearing in the California State Assembly and Senate, the Chancellor’s Office tried its very best to undermine the voices of students, faculty, and community members.

He appointed representatives to testify about the sanctity of so-called faculty governance, legislative intrusion, and his proposal to use a multicultural requirement in lieu of Ethnic Studies to try to squash calls for AB-1460. White and Executive Vice Chancellor Loren Blanchard have a proven track record of implementing policies that undermine the fidelity of Ethnic Studies.

In 2017, for example, White implemented Executive Orders 1100R and 1110, which tried to dismantle Ethnic Studies requirements in the CSU (without faculty consultation) (Faculty Senate Resolution, October 26, 2017). At the California State University Northridge (CSUN), for example, its cross cultural competency requirement housed under general education was gutted.

After students walked-out, protested, and boycotted, the Faculty Senate at CSUN voted to reject his executive orders three different times. In 2019, CSUN’s Faculty Senate took a vote of no confidence in White, citing his “failure in his responsibility to demonstrate effective leadership particularly during a time of national crisis where white supremacy, racism, sexism, homophobia, and xenophobia are normalized and enacted” and voted in favor of supporting AB-1460 in February 2020 (CSUN Faculty Senate Resolutions February 20, 2020 and February 14, 2019). Actions taken by faculty to preserve our own autonomy stems from the urgency to pass AB-1460 in order to avoid a second round of violations against faculty governance enacted by the Chancellor’s Office.

After six failed attempts in four subcommittee hearings and two floor votes in the California Senate and State Assembly to try to undermine Weber’s bill, White’s Office is currently proposing a substitute for AB-1460 called “Ethnic Studies and Social Justice” (ESSJ). At a Board of Trustees meeting May 12, 2020, when presenting White’s proposal, Blanchard and CSU Associate Vice Chancellor Alison Wrynn presented an inaccurate portrayal of intersectionality by substituting race for another category that fits within a random marginalized population. In its presentation, White’s Office stated:

“Courses that meet this requirement shall either focus on the intersection of race and ethnicity and describe how resistance, social justice and liberation as experienced by communities of color are relevant to current issues (communal, national and international); or they shall focus on other factors in understanding hierarchy and oppression, such as class, gender, sexuality, religion, spirituality, national origin, immigration status, ability and/or age” (Board of Trustees Meeting, May 2 in 2020).

According to Kimberlé Crenshaw, who founded a sub-field in Ethnic Studies called Critical Race Theory, to use the concept of intersectionality correctly means to examine issues of race and racism as they intersect with gender, sexuality, class, nation, and ableism (Crenshaw, 1991).

White’s proposal undermines the significance of Crenshaw’s foundational concept of intersectionality by substituting race with any form of marginality. On July 21, 2020, the CSU Board of Trustees will consider a second reading of ESSJ and make its decision by voting on it. In a rushed move to try to push ESSJ through the Board of Trustees in order to demonstrate to the California legislature that his proposal is an adequate replacement for AB-1460, White has proven not to uplift the voices of Ethnic Studies experts. Instead, ESSJ has the potential to wreck the foundation of one of the core principals of intersectionality: a focus on race and racism that responds to the needs of Black, Indigenous, Chicanx/Latinx and Asian American women, queer, and gender non-conforming folk.

As the nation steers its interests in favor of redressing historical inequities that help shape systemic racism, Ethnic Studies will help to close the racial divide in the CSU system. AB-1460 puts Ethnic Studies faculty into the driver’s seat to ensure educational equity and anti-racism are a top priority in the CSU. As students walk out onto the streets in protest to demand for social change in light of Black Lives Matter by defunding police on K-12 and college campuses, and the abolition of state-sponsored terrorism propagated by police departments across the U.S., Californians cannot afford to not take race any less seriously. The Trump administration’s war against DACA, its failure to adequately provide guidelines to protect people against COVID-19, the rollback of environmental protections in Flint, Michigan, while watching the institutional crisis of our healthcare system, all point to institutional failures that protect frontline communities. The CSU trains the highest proportion of professionals to work in the public sector. An Ethnic Studies requirement will help to protect civil rights as CSU graduates move into public sectors employed as teachers, doctors, and public health professionals in service of California’s polity.

In the words of novelist James Baldwin, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” As I close my opinion piece, I want to lift up calls for dignity that demand another world must be made possible. AB-1460 is built upon a 52 year legacy of Ethnic Studies that started out of social unrest where students demanded a curriculum that spoke to the experiences of Chicanx/Latinx, Black, American Indian, and Asian American communities. As we look towards the future of how to stop police violence against Black communities, detention and deportation of Chicanx/Latinx families, violation of American Indian sacred sites and contamination of water at Standing Rock, and racist attacks made against Asian Americans and Asian immigrants in the midst of COVID-19, California has an opportunity to create radical change in our public education system. As Governor Gavin Newsom prepares to review Weber’s bill, Californians can speak out against bigotry, intolerance, and racism by asking the Governor to sign AB-1460.

Stevie Ruiz is an assistant professor in the Chicana/o Studies Department at California State University, Northridge. He holds a Ph.D. in ethnic studies from the University of California, San Diego.