Op-Ed: Void for its vagueness: CSU Board of Trustees passes social justice requirement, ethnic studies community stands in support of AB-1460

Courtesy of Professor Tracy Buenavista of the CSUN Asian American Studies department

August 3, 2020

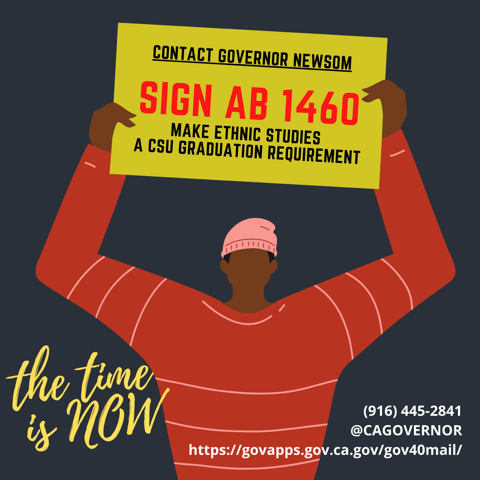

On July 22, 2020, the California State University (CSU) Board of Trustees passed Chancellor Timothy P. White’s “Ethnic Studies and Social Justice” (ESSJ) requirement (Board of Trustees, July 21, 2020). The Chancellor’s Office developed its own proposal that allows undergraduate students to fulfill ESSJ without the completion of Ethnic Studies coursework. At no point did any academic body endorse Chancellor White’s ESSJ proposal, including the Academic Senate of the CSU, Ethnic Studies Taskforce, and Ethnic Studies Council (Board of Trustees, Jan. 21, 2020). Void for its vagueness, ESSJ mandates a social justice requirement without having to take classes that address race and racism.

All Ethnic Studies departments in the CSU support AB-1460, a bill sponsored by assemblymember Dr. Shirley Weber who served as chair of Africana Studies at San Diego State University, that mandates all undergraduates to complete a course that covers the racialized experiences of African Americans, Asian Americans, American Indians, and Chicanx/Latinx populations. Five members of the Board of Trustees who included Silas Abrego, Lateefah Simon, Maryana Khames, Hugo Morales, and California State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, bravely stood in agreement that Ethnic Studies courses should be mandated in an Ethnic Studies requirement.

In an open meeting, 13 trustees were locked in their position to pass ESSJ despite over 150 community members who called to weigh in support of AB-1460 since May 2020. Trustee Rebecca Eisen was bold enough to claim White’s proposal was “Ethnic Studies plus” because it allowed for greater flexibility to opt out of courses that required a focus on race and racism (Board of Trustees, July 21, 2020). Words used to describe Weber’s bill included too “traditional” and “narrow”, while White’s proposal was presented as “futuristic” and “forward thinking,” language that is commonly used to undermine Black women’s contributions inside academe (Gutierrez, et al., 2012). We take issue with non-experts taking uninformed positions to pass educational policies that help to undermine Ethnic Studies.

In our public opinion piece, we write as two teacher-scholars who each earned a Ph.D. in Ethnic Studies, published extensively in Chicana/o Studies, and teach students new directions in our respective sub-fields: environmental justice and prison abolition. We contest inaccurate statements made by some members of the Board of Trustees and the Office of the Chancellor that Ethnic Studies is a field stuck in “tradition.” Instead, we assert concepts like intersectionality, queer of color critique and women of color feminism emerged out of Ethnic Studies and continue to be the bedrocks of our discipline.

Under ESSJ, students can take a course outside of Ethnic Studies without addressing race and racism. For example, as a Ph.D. student in Ethnic Studies, Dr. Martha D. Escobar enrolled in a course in her campus’ Sociology Department called “Sociology of Gender” where she was required to present on her professor’s book, which maintained that white female financial executives were radically transforming ideas about work and family. Given her expertise in women of color feminism, Escobar questioned whether white women were independently successful. In her rebuttal, she explained that white women (as a group) have historically benefitted from the invisible labor performed by Black and Latinx women. Escobar’s experience is unfortunately a common one shared by many students who take classes in disciplines where faculty are not familiar with debates in Ethnic Studies but who can teach classes that fulfills requirements like ESSJ. Under AB-1460, students will obtain a well rounded education where people of color’s identities are taught in relationship to gender, sexuality, and class from a comparative perspective.

Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and Kumu Hina are just a few examples of transwomen of color who are celebrated in Ethnic Studies. Dr. Stevie Ruiz, for example, teaches “Race, Racism, and the Sciences” in Chicana/o Studies at CSUN where students learn about the experiences of women and queer people of color in the sciences. They learn about the ways in which mahu (third gender persons) are revered as spiritual healers and educators of traditional science among Native Hawaiians; Latinas who fought against forced sterilization in Quilligan v. Madrigal; and Black women who were enslaved were subjected to experimentation in order to advance gynecological science by its founder James Marion Sims. From an institutional perspective, students learn about the comparative and relational nature of race to understand how racism is pervasive in a multitude of institutions that pretend to be objective like medicine, science, law, and education. Rather than “pick” a vague marginality that does little to challenge students’ world views, Ethnic Studies taught by its experts equips students to understand the full capacity of institutional racism and how power functions to classify, stereotype, and discriminate.

Uneducated guesses about whether Ethnic Studies can forgo its commitment to anti-racism is not debatable. In the words of Trustee Simon, it is disingenuous to call ESSJ an Ethnic Studies requirement if Ethnic Studies courses are not required (Board of Trustees, July 22, 2020). After AB-1460 is signed by Governor Newsom, Ethnic Studies faculty hope the California legislature will step in to evaluate the ways in which the Board of Trustees members handled our Ethnic Studies requirement, especially since the entire Ethnic Studies community was upfront about our objections to ESSJ, and stands in full support of AB-1460. As California State Senator Ben Allen stated when giving his public comment in favor of AB-1460, “the approval and appointment of these folks [trustees] who we [the legislature] send to run the UC and Cal State system…maybe that process is too closed and maybe we are not asking enough questions of members to ensure we really trust that they are going to take the kinds of lessons we are discussing to heart when they are making tough decisions at the Board” (California State Senate Floor Session, June 18, 2020).

We recommend for the Board of Trustees to take pause and reflect on unconscious biases that were clearly made visible at the CSU meeting, especially since those faculty who were ignored were 99% people of color by a majority of white trustees. Actions taken by the Board of Trustees to ignore faculty and students of color underscores the urgency for Governor Newsom to sign AB-1460 to help redress the legacy of historical racism that still is pervasive inside the largest public university system. As California voters revisit the harm done by Proposition 209 this coming November, AB-1460 aligns nicely with the future of California’s public education system. Governor Newsom can be a leader in the fight against institutional racism in the CSU to help protect academic freedom and civil rights by signing AB-1460.

Stevie Ruiz is an assistant professor in Chicana/o Studies and Martha Escobar is a professor in Chicana/o Studies at California State University, Northridge.