Unhoused community in L.A. face more challenges since COVID-19

August 26, 2020

For several years, Los Angeles has had one of the biggest populations of unhoused people in the country. A 2020 report by the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development found that in 2019, while homelessness declined in most states, it increased by 16.4% in California.

66,436 people in L.A. County are currently unhoused, according to a recent report by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. The report found that 59% of those people cited economic hardship as the reason for being unhoused.

Gov. Gavin Newsom warned at the beginning of the pandemic that the large unhoused population in L.A. would be among the most at risk for catching COVID-19. In order to try and mitigate the spread, the state of California launched Project Roomkey, a $150 million project to house 15,000 unhoused people who are at a high risk for COVID-19.

As of Aug. 25, 4,180 people are currently enrolled in Project Roomkey, according to LAHSA. Project Roomkey has 705 clients in the San Fernando Valley as of Aug. 25, according to an update from the L.A. Emergency Operations Center.

In spite of the county’s mitigation efforts, several shelters in the L.A. area had COVID-19 outbreaks, including dozens of cases at the Union Rescue Mission — a program on Skid Row and one of the largest homeless shelters in L.A. County.

L.A. County recorded 33 COVID-19 deaths and 1,498 laboratory-confirmed cases among the unhoused population as of Aug. 25, according to the L.A. County Department of Health Services.

Cases in the San Fernando Valley, where LAHSA reported that 9,274 people are unhoused, are not as high as in other parts of Los Angeles like south and downtown L.A., but staff from shelters in the San Fernando Valley said that keeping COVID-19 out of shelters and housing has been an ongoing effort.

Spaced out beds, difficult quarantine logistics, abandoned common areas, canceled Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, limited visitations and daily temperature checks are just a few of the scenes described by staff at three San Fernando Valley programs. Staff also expressed concerns about guests’ mental health and sobriety.

Cassie Leon, program coordinator at the San Fernando Valley Rescue Mission, a family shelter program in Northridge, said the shelter normally takes in 10 to 20 families per month, but currently, only eight families are in residence and the shelter can only take in four families per month.

“It’s hard because the need is there, but we can’t meet it because of restrictions,” Leon said.

Incoming residents at San Fernando Valley Rescue Mission must quarantine for two weeks in a separate building, only leaving for fresh air. Leon said that the isolation has been so tough for some that they quit even before beginning the shelter’s 90-day program.

“It’s hard when you can’t even go to the grocery store — that’s what I do when I need to escape,” Leon said.

Leon expressed concerns that distance learning will be a problem for her clients with children. LAUSD began distance learning this week, but students experiencing homelessness experience particular disadvantages. Leon said that the program has set up a distance learning classroom, equipped with Wi-Fi, computers and school supplies, but even with these resources, she said it will be a difficult year.

“Distance learning is tough! It’s hard for kids to stay focused for long periods of time on Zoom,” Leon said. This was echoed by Laura Harwood, Director of Residential Programs at Hope Of The Valley, who oversees three family shelters that house about twenty-five families overall. “I can’t imagine being five years old and having to do online schooling,” she said. “I think there’s going to be a lot of grades falling, a lot of kids behind.”

Bitsy is one of those living in the shelters who is dealing with the added stress and frustration to an already difficult year. Bitsy lost her housing last year after a long struggle with immigration drained her finances and a difficult pregnancy left her unable to work. She has been living at the Shepherd’s House, a Hope of the Valley program, since January. Through the pandemic, she has been taking care of her four children while taking classes to get a degree.

Bitsy said that she wants to do the best with what she has, but it isn’t easy. Even arriving at the Shepherd’s House was stressful – she was hopping from couch to couch, being placed on waiting lists, and not getting help she desperately needed. “We’re getting all these funds to help the homelessness, but we’re not really being helped like the government makes it look like,” she said.

A few times, Bitsy had to pause, battling tears. “It’s like putting an anchor on your foot and throwing you in the ocean,” she said.

In the beginning of the pandemic, Bitsy said her and her children had to stay in their shared room all day. “I have zero time to study,” she said. “My only time to study is in the middle of the night.” She said her children struggled to adjust to the new reality. “Kids go crazy when they’re locked up in a room, there was a lot of arguing in the beginning…this is really difficult on children. They just want to be kids.”

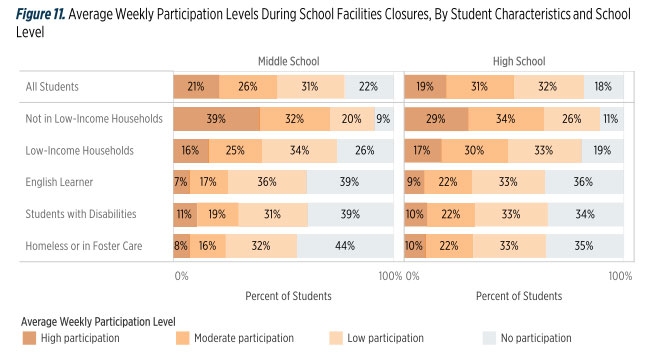

A Los Angeles Unified School District report, found that about 66% of unhoused middle school students participated in distance learning on a weekly basis since LAUSD schools closed on March 13. By comparison, 91% of middle schoolers who were not in low income participated in distance learning on a weekly basis.

Jackie Chavez, executive director of Community Bridge Housing, a recovery home in Sylmar, says they have completely stopped admissions because of their existing at-risk population.

“We want to take care of the people we have,” she said.

Chavez said that the shelter normally holds Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings, but those have stopped.

“My residents are struggling and it’s difficult for them to maintain sobriety,” Chavez said.

Chavez said Community Bridge Housing has had two COVID-19 cases since March.

Both Leon and Chavez expressed concerns that economic hardships will continue to exacerbate the number of unhoused people, even though some of their residents are going back to work.

Leon said that some residents returning to work while others stayed behind caused frustrations for her guests. “Most of the families were at home with nowhere to go … that caused tensions for a while, some of our guests were able to go back to work because they worked in grocery (stores.)” Harwood said that allowing residents to rejoin the workforce has been difficult – any COVID-19 case in a house puts all of the residents in quarantine, and there have been two outbreaks at houses already.

Even with the uncertainty and day-to-day changes the pandemic has brought to shelters, it has also provided a well-needed change in perspective, according to Leon.

“It’s caused [the residents] to really grow together and be a tight knit group … if they hadn’t had these frustrations in the beginning, it wouldn’t have allowed them to dig deeper and connect,” Leon said. “It allows us to replan, restructure and make sure we can meet the needs of the community as it’s changing.”

Health officials have lauded their efforts to assist the unhoused population during the pandemic — L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer praised Project Roomkey as a “comprehensive response,” but Leon and Chavez felt differently.

“The city isn’t doing enough,” Chavez said. “There’s way too many homeless people in Los Angeles to test and track everyone.”