CTVA Chair recounts personal experiences, highlighting importance of accurate media representation

August 20, 2020

As Dianah Wynter sat in front of her family’s television set as a little girl, a newly aired sitcom transformed the screen into a mirror.

For the first time, Wynter, CSUN’s department of cinema and television arts chair, saw her mom in Diahann Carroll’s character, Julia Baker, in the 1968 NBC series, “Julia.” The show was the first weekly series to depict a middle-class African American woman in a non-stereotypical role on TV.

Like Baker, Wynter’s mom, Lena Wynter, was a nurse. Wynter remembers watching her mom get dressed before she left for her evening shifts at the Brooklyn Jewish Hospital wearing the quintessential nurse uniform —similar to the one worn by Baker in the sitcom.

She said seeing someone in the same profession as her mom on TV had a powerful impact in her household.

“We were very proud of my mom when that show came. I mean we were proud of her no matter what, but that really meant something — it meant that there was television reflecting the lives that we lived,” Wynter said.

The impact the experience had on Wynter, who is also a female Jamaican American director, illustrates the importance of accurate African American portrayals and storytelling in the media.

Wynter said she grew up in a Jamaican American household in Brooklyn, New York, during a time when there was not a lot of television her family could identify with. Much of the characters Black and brown people often played criminal roles on screen, which was not reflective of her reality. Instead, some of her favorite programs to watch on TV included “The Brady Bunch” and “The Partridge Family.”

“We couldn’t relate to criminals, because we didn’t know anybody like that,” she said. “Now, if you’re in a neighborhood where there are criminal characters walking around, then there’s a greater likelihood that those characters on television might stick with you.”

Wynter, who also teaches the media theory and criticism option at CSUN, said misrepresentations of minority groups in the media can have a negative impact on people who are not exposed to diverse communities likely maintaining those attitudes into adulthood.

“Representation in all media tends to be a reflection of the values that are placed on particular people — their status,” she said. “So when people are misrepresented or there are distorted representations or there are no representations, it will affect the societal attitude.”

She said the invisibility of African Americans can be viewed as indifference.

“When a society is indifferent to whole segments of its population, it is something that impairs the society as a whole,” she said.“There has been a great deal of indifference toward African Americans and some scholars would attribute the negative images of Black people in the media to fostering indifference, hostility and even cruelty.”

Wynter said the internet can be used in a way that further perpetuates hate by people reinforcing these harmful ideas with others that share the same beliefs in a virtual echo chamber.

“Imagine watching television that only has one channel and the channel is that and everyone watches it and everyone who’s on it looks exactly like you,” she said. “Then your whole perspective of the world is completely warped and unhealthy. Those individuals are robbing themselves of the real experience of the world and then whipping themselves into very unhealthy activities. Media is powerful, it really is, when there is nothing else balancing it.”

In contrast, she said most people who are surrounded by diverse communities can easily disregard the stereotypes they see on screen because the people in their environment will contradict the common inaccuracies in TV and film.

Wynter’s earliest memory of exposure to African American culture in the media was watching The Supremes guest star on variety shows as a child in the 1960s.

“They represented Black femininity,” she said. “They dressed in couture — the gowns and the hair and the makeup were just so elegant and beautiful. And that was my understanding of Black women. It was nice to see it coming out of the TV set.”

From Wynter’s world view, these images of The Supremes on TV were significant because they were both positive and relatable.

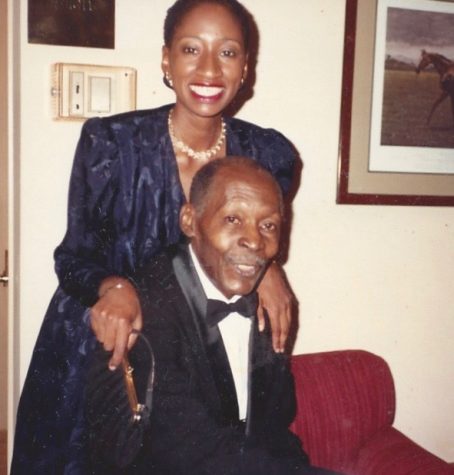

The Black women in her life were unlike a lot of the portrayals of women of color on the screen. So when her mom and fellow nurses formed the Jamaica Nurses Group of New York to raise money for nursing scholarships, they dressed up for the awards banquet; nothing was out of the ordinary.

“They wore these gowns and I was like ‘OK. This is normal,’ but then you turn on the television and Black women are invisible,” Wynter said, adding that Black women on screen were usually either portrayed negatively or the only person of color visible on screen, which was not reflective of her reality.

Wynter said “a great renaissance of Black programming and films” arrived in the 1990s, as shows like “A Different World” — a spin-off of “The Cosby Show” — and “The Fresh Prince of Bel Air” gained popularity.

“It was a time of inclusion, a time of innovation and a time of acceptance,” she said.

Black characters in shows like “The Fresh Prince of Bel Air” — which starred the actor Will Smith as the titular character — were showing Black life in a light that contradicted the norm in mainstream media.

“The whole country was in love with Will Smith — the whole world pretty much. He was so original and so full of the joy of being alive and being himself,” Wynter said. “A very powerful thing to see for anybody, but for young Black individuals, it was very important to see someone who’s in love with life and in love with who he was. You know, we’d be like ‘Oh, “The Fresh Prince Bel Air” is silly,’ but it was more important than you think.”

This period ended during the first decade of the new millennium, according to Wynter said.

The Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artist casting data showed that “African American roles showed the largest drop in proportion to total roles, falling from 14.8% in 2007 to 13.3% in 2008. Each category of production type saw a decrease … In 2008, African Americans constituted 9.5% of low budget roles, which was down 6.5% from 16% of roles reported in 2007.”

“It just stopped like someone put the brakes on,” she said. “Black and brown faces disappeared on television. It was harder for Black filmmakers to get their movies made and it was startlingly apparent. It was just in your face.”

Wynter said Black and brown people telling their own stories is the only way to ensure it’s told in an authentic way.

“It really comes down to who is running the show — who is making the movies — and if we’re not telling our own stories, then they tend to be very distorted,” she said. “And that seems to be a big hurdle that we still have to overcome is African Americans telling African American stories.”

Wynter joined the Director’s Guild of America in 1997. That same year the DGA’s African American Steering Committee hosted “Hollywood’s New Deal: Black Women in the Director’s Chair,” where Wynter was one of the 15 members recognized for their achievements.

At that point in her career, she directed an ABC Afterschool Special called “Daddy’s Girl,” which earned her a Daytime Emmy nomination for Outstanding Directing in a Children’s Special; some of her directing credits include “Getting baby off the bottle,” “The Secret World of Alex Mack,” “Norville and Trudy” and “The Journey of Allen Strange.”

Despite some of the resistance to diversify the industry in years past, today, she said she’s proud when looking at content produced by this generation. She said shows like “Queen Sugar,” “Atlanta” and “Insecure” are bringing Black stories and visibility to the forefront of media.

“I was hoping this would be the landscape I would be coming into 20 or 23 years ago when I first came here,” Wynter said. “But to see it come now, and to have a feeling of almost a knowingness that it’s going to keep improving like this — it’s great.”