Majority of police reform bills struggle to pass California Legislature

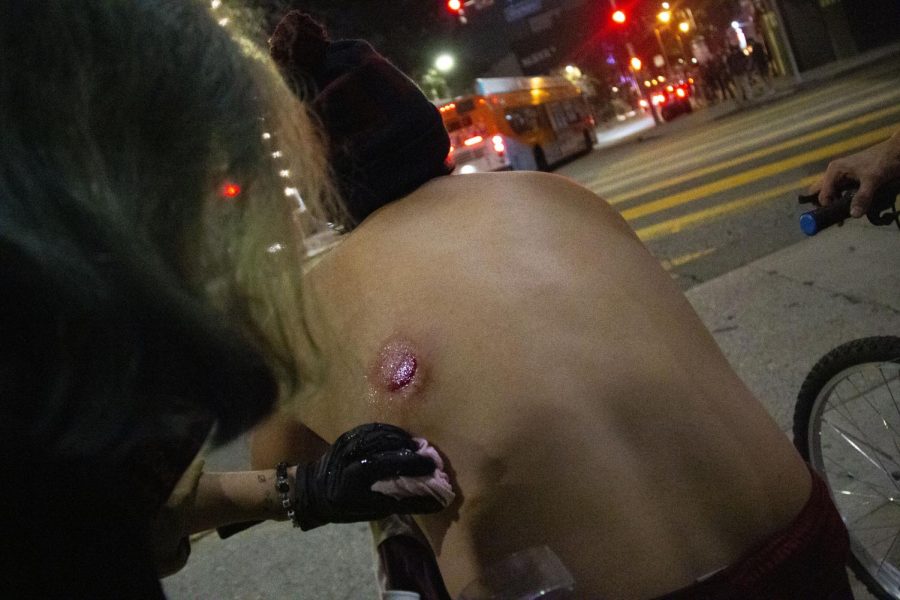

An LAPD officer raises his less-than-lethal weapon as protesters begin throwing debris at police during a protest in downtown Los Angeles on May 29.

September 14, 2020

Here’s what you need to know:

- The California State Legislature attempted to pass several bills related to police reforms on their last day before the recess, on Aug. 31.

- Several bills related to regulating the use of tear gas and rubber bullets, investigating fatal officer-involved incidents and decertifying officers found guilty of misconduct were on the floor.

- Although activists are pushing for strong police reforms across the country, California lawmakers are struggling to make those reforms a reality.

During the final day before recess in the California State Legislature, lawmakers scrambled to vote on dozens of bills on Aug. 31.

California senators and Assembly members grew impatient throughout the night due to technology issues and scuffles between lawmakers. Over a dozen police reform bills were on the agenda that night.

Protesters across the country have been demanding reforms in policing in the wake of cases of police violence, such as bans on chokeholds and the restrictions of “less-than-lethal” weapons like tear gas and rubber bullets.

However, many of these reforms are failing to pass at local and state levels.

Assembly Bill 66, authored by Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D-San Diego) was aimed at minimizing the use of “kinetic energy projectiles or chemical agents” to disperse crowds at protests or gatherings, and ordered law enforcement agencies to report any use of such weapons that resulted in an injury.

AB 66 did not pass.

The Los Angeles Police Protective League is the union for Los Angeles Police Department officers. Dustin DeRollo, a spokesperson for the LAPPL said that the union needs “alternatives to lethal force” to protect officers.

“It’s a fact that we’ve had officers who are suffering things like frozen water bottles [and] bricks to the head, [and] laser pointers,” DeRollo said. “There’s got to be options for what officers can use.”

The LAPD is currently involved in a class action lawsuit brought by the Los Angeles chapter of the National Lawyers Guild and Black Lives Matter Los Angeles, accusing officers of exposing protesters to the coronavirus and using excessive amounts of force at protests.

Shaun Rundle, deputy director of the California Peace Officers’ Association, said that although the organization supports limiting the use of less-than-lethals, AB 66 would have prevented officers from using those weapons in other incidents like barricades, which he believes is a safety concern.

“When things go awry, we want to make sure that tools aren’t taken from their toolboxes to keep the crowd safe,” he said.

Senate Bill 731, authored by Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena) also failed to pass. SB 731 would have established a decertification process of police officers fired for misconduct, meaning that an officer could not continue their employment in another state.

A poll by UC Berkeley’s Institute for Governmental Studies showed that 80% of respondents favored laws that would prosecute officers who use excessive force and 70% favored the right to sue officers for misconduct and excessive use of force.

Although SB 731 was supported by BLM-L.A. and the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, staffers for Bradford and Assemblymember Kevin McCarty said that police reform bills faced immense pushback from police unions and law enforcement groups.

Multiple police unions, including the LAPPL and CPOA, said they felt that language in the recent bills was too vague and complex, and that the legislation was unfair.

Bradford’s office disagreed. “They felt the process [of decertification] was unfair to officers. We didn’t believe that,” said a staffer for the senator.

The LAPPL has publicly expressed disdain for SB 731. DeRollo confirmed that the organization openly lobbied lawmakers not to pass the bill.

“It’s a horrible bill,” DeRollo said. “Top to bottom, it was poorly written, it was done in haste, it was done behind closed doors. It was unique in that the bill’s author would not meet with anybody from law enforcement.”

DeRollo said that the LAPPL requested to meet with Bradford about the bill and their request was denied. A staffer for Bradford’s office said that to their knowledge, the LAPPL did not reach out to their office to make an appointment.

AB 1506, authored by Assemblymember McCarty, would create a separate department within state government to review and investigate all use-of-force incidents that result in the death of an unarmed citizen. The bill would have also required the Attorney General to publish reports about these incidents.

AB 1506 passed.

The day before the California State Legislature met, Dijon Kizzee, a 29-year-old Black man, was fatally shot by two L.A. County sheriff’s deputies.

“These bills are common sense reform,” McCarty said.

Rundle said that the CPOA supports holding officers accountable, but AB 1506 would have put financial strain on smaller agencies and created logistical problems.

“It’s not that we don’t want those records released,” Rundle said. “It’s a fiscal impact on an agency on a shoestring budget.”

Lawmakers expressed hope that the bills that did pass, such as AB 1506, will be a significant step towards creating tangible police reforms.

“The goal of these bills is to restore transparency and accountability in police departments and local law enforcement,” McCarty said. “My hope is that they can help begin to repair the trust that has been lost between police and the public.”

*Editor’s note: Edited for style and to provide more context in photo captions at 11:58 a.m. on Sept. 15.