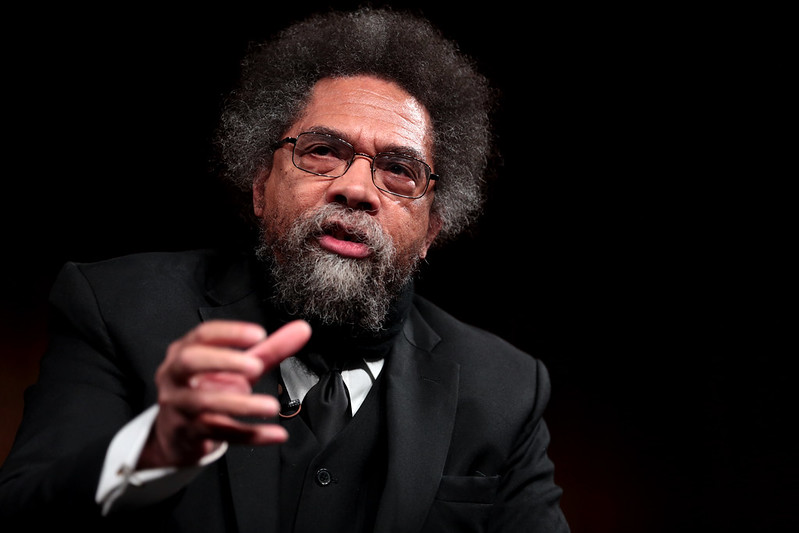

Walking the tightrope of racial battle fatigue with Cornel West

March 9, 2021

Finding the balance between fighting for social justice and maintaining one’s well being is like walking on a tightrope. As the fight against injustice takes a mental and physical toll on the people pushing for change, how can they continue to demand justice without sacrificing their own health?

Students, faculty and staff had a candid and enlightening Q&A with philosopher, author and social critic Cornel West about the challenges of racial battle fatigue in “Walking the Tight Rope: Addressing Racial Battle Fatigue” on Feb. 26.

Where racial fatigue comes from

The conversation addressed America’s ongoing struggle to tackle racism and inequity, which created what some call racial battle fatigue. The term, originally coined in 2008 by critical race theorist William Smith from the University of Utah, is used to describe the negative and racially-charged experiences of people of color, particularly Black people.

West, a professor at Union Theological Seminary, defined racial battle fatigue as “the ways in which Black people can be overwhelmed by the sheer insanity and absurdity of white supremacy bombardment” and the misinformation told about the Black community.

He added that it includes “all the lies told about Black people, that we’re less beautiful and less intelligent. All the crimes committed to Black people, day in and day out for 400 years.”

In order to address racial battle fatigue, everyone must first understand what went into shaping and molding our society, according to West.

“That’s the beginning; we have to have a sense of who we are, in our identities. Whatever it is, racial, gender, sexual orientation, it has got to be grounded in moral and spiritual integrity and global solidarity,” he said.

The summer of racial reckoning that occured after the consecutive deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd ignited a national movement to confront racialized trauma and institutional racism.

In addition, systemic racism has created an additional pandemic within the COVID-19 pandemic as Black, Indigenious and people of color are disproportionately impacted by the coronavirus. A recent study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention revealed that since the coronavirus outbreak, Black Americans’ life expectancy dropped by nearly three years while Latino Americans’ life expectancy dropped by nearly two years.

People of color — as well as the poor and working class — are taking the brunt of the pandemic.

In a post-pandemic United States, West’s priorities for advocacy are poverty, lack of quality education and healthcare. He said people cannot talk about Black freedom without eliminating the class divide within the country. While his beliefs may seem far-fetched to some, he believes that having an awareness of the class divide is a good place to start.

“We need to know what the standards are, and how far away we are, so we don’t end up rationalizing to ourselves to think these are great breakthroughs for progress, when in fact they are very small steps,” West added.

In response to a question about the Biden-Harris administration, West said that the administration should address racial inequity through the 14 Policy Priorities from the Poor People’s Campaign, which drafted 14 policies aimed to eliminate poverty and systemic racism and empower marginalized groups. The Poor People’s Campaign is rooted in the teachings and goals of Martin Luther King Jr., who was planning a large demonstration in Washington D.C. to unite and fight poverty weeks before his assassination.

Disentangling racism from the fabric that is America

In his 1993 book, “Race Matters,” West argues that society needs to understand that racism is interwoven into the fabric of America. Racism cannot be eradicated until the country understands that “race matters” in everything we consider “American.”

As such, the Black community needs to unlearn their own biases and stereotypes that are rooted in white supremacy in order to battle racial bigotry, according to West. He said it’s impossible for a person, no matter their color, to grow up in a civilization deeply rooted in white supremacy and not be affected by it.

“The last thing we need is Black people who love everybody but Black people. That’s pathological. That’s sick,” West said. “When you really love the folks around you, by the time you get to the vanilla side of town, you know what love is. It’s not a plaything, it’s not manipulation, it’s heightened vulnerability.”

He said freedom goes beyond just liberating Black people; Class, age, gender, region and other factors play a role in the liberation of all people from oppression.

He added that talks of freedom mean little when these issues of inequity stand in the way locally and globally.

“You can’t talk about Black lives matter and act as if the lives in Pakistan and Afghanistan, the lives in Libya, don’t matter when those drones are dropped,” West said. “You have to raise your voice. But that’s what got me in trouble with brother Barack Obama, right?”

West has a long history of being unapologetically critical of former President Barack Obama for putting corporate interest before the citizens of America when he bailed out Wall Street. While he recognizes the phenomenon behind Obama’s legacy of being the first-Black president elected to the U.S., he argued diversity has to be more than symbolic gestures.

Diversity is about democratizing and sharing power, and more than just placing “tokens” in power for the sake of optics.

According to West, the connection between racial battle fatigue and the increase of social justice movements like Black Lives Matter has allowed young people to put pressure on the establishment and challenge the status quo.

“Young brothers and sisters say ‘We are tired of police brutality and police crimes.’ ‘We are going to organize; we’re going to put our bodies on the line,’” West said. “In the name of truth and in the name of justice.”

Why love is the answer

Following in the footsteps of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement, West said the answer to hate is love.

According to West, taking a nonviolent approach to seek out the truth and speak up against social inequities for all people from all backgrounds is what will move us toward the path of justice.

“Justice,” West said. “is what love looks like in public.” Meaning: love is fair, equal, just and the only way to address hate.

West said that the Black community wants human success and greatness that goes beyond the quest for simple pleasures and materialistic success.

However, a “commodified culture”, a culture that has reduced everything down to success instead of greatness, stands in the way of the BLM movement and the Black community. Superficial success has created a “wave of black peacocks” within the community.

“‘Look at me, look at me, I’m so rich. I’m so smart,'” West mocked. “I can hear grandmama say ‘Peacocks strut because they can’t fly.’ We’ve been a people who have always wanted to fly.”

In order to reduce racial battle fatigue, BLM will have to keep love and justice at the center of the cause, according to West, as a desire for revenge arises when advocates become impatient and exhausted in fighting social justice issues.

He recognized how difficult it is to balance on the tightrope.

“‘Do you get tired?’ Absolutely,” West said. “I’m a bluesman. The heartache is there every morning.”

Yet, he always has a smile on his face because the greats that came before him showed him how to be resilient.

Channeling ancestors for strength

West said that by channeling the strength of the ancestors and the legends who have faced adversity and by applying love, people could move through despair and apathy. He said it gives people distance from the pain not to feel overwhelmed by social justice exhaustion.

West spoke of the bravery of Billie Holiday and how she used her talent, style and technique so that she could sing “Good Morning Heartache” during a time in which he called the “American terrorism” of the “neo-slavery of the Jim and Jane Crow” era. West was inspired by how Holiday sang her way through a historically challenging time in America’s history.

Still, the Black community has faced many different forms of domestic terrorism. West said that despite the amount of trauma directed at the Black community, they have continued to produced freedom fighters like famous anti-slavery author Frederick Douglass and healers such as singer/songwriters John Coltrane, Curtis Mayfield and Marvin Gaye.

West said the question becomes under what conditions can Black people continue to produce the same kind of love, community and joy?

“So that white supremacy is not our point of reference so that the white gaze is not the lens through which we view each other, or ourselves,” West said. “Our gift to the world has been disproportionately influential because we have been willing to be freedom fighters and wounded healers, and then we’ve been hated for 400 years, hated so intensely, and yet we keep dishing out love wardens.”

In order to combat hate, West introduced the Christian ideology of “kenosis,” which he defined as learning to give oneself up to something bigger. But above all else, West encouraged the attendees to practice the art of over-loving.

“Martin [Luther King Jr.] over-loved us, Malcolm [X] over-loved us, Fannie Lou Hamer over-loved us. Irene West and Clifton West, they over-loved me. And all that love is going to keep coming through me,” West said. “It’s not going to stop … because that’s the kind of people that I come from.”

He said that freedom fighters must be prepared to go the distance on the long and winding road to justice. He encouraged the audience to stay rooted in integrity, and choose to serve truth and justice.

At the end of the discussion, he praised the students and faculty of CSUN for their engagement and critical reflections that were “grounded in serious commitment” to the cause to fight social injustice.

“Something mighty is taking place in Northridge and I think that’s very important,” West said.