Latino families in Los Angeles share their worries, fears on reopening schools

April 23, 2021

San Fernando Valley Latino parents are unsure of Assembly Bill 86, a plan recently approved by California lawmakers to reopen schools by the end of April.

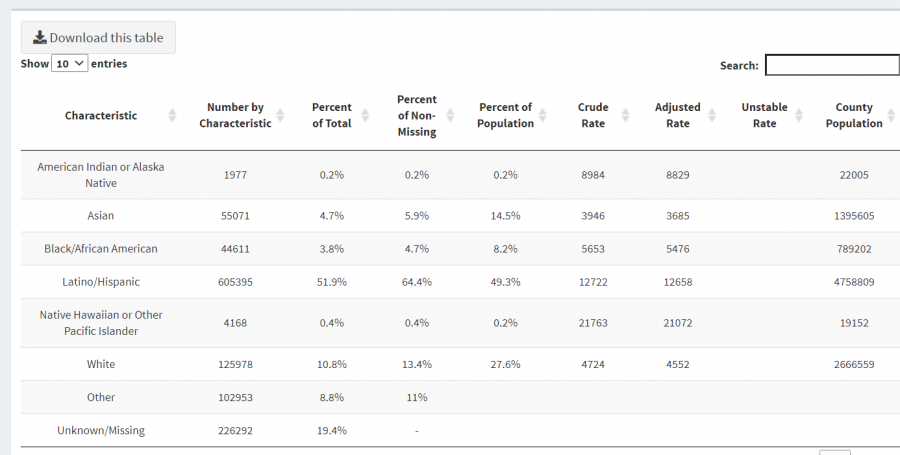

Some Latino parents share similar fears about their children contracting COVID-19 when schools reopen. Their fear stems from the fact that infection rates remain high in the Latino community, as the community accounts for half of the COVID-19 cases in Los Angeles County.

The risk of exposure for Latinos is often tied to their jobs. The Los Angeles Times found that Latinos make up a majority of the workforce in essential jobs, such as food service workers, retail salespeople and construction workers. Workers in such jobs face a higher risk of exposure to the virus.

Some Latino families are eager to have their children return back to school, however, other parents are afraid to put their children at risk of exposure.

Cassandra Garcia, 35, a mother of two girls and a cosmetic associate at Macy’s, is hesitant to send her daughters back to school. Her eldest daughter, Layla, 13, is currently a seventh-grader at Patrick Henry Middle School and Lola, 7, is in first grade at Lashon Academy. Both of her daughters are doing remote learning.

Her husband Juan Garcia, 37, worked in construction before the pandemic. After schools closed, he decided to stay home to help his daughters with their online classes. He explained how remote learning was a struggle in the beginning but admitted that he came to enjoy it.

“I know what they are doing and what they need to improve on in school. I get to spend more time with my daughters,” he said.

Garcia’s main concern is how school staff and teachers will make sure students follow simple new guidelines, such as social distancing or mask-wearing. She is afraid that Lola won’t keep her mask on or wash her hands. Garcia said she can’t imagine Lola being able to manage any safety procedures by herself and she doubts Layla will either.

The Garcias said the new plans to reopen schools are not clear enough for them to send their daughters back to school. Kids will be required to wear their masks, sanitize their hands and maintain social distance from their friends and teachers.

“It’s like sending my kid into a war zone,” Garcia said.

The Garcias hope that it will be safe for their daughters to go back to school one day. They want them to have a normal childhood. However, she would rather have her daughters go back to school when everything goes back to normal, without the need for safety precautions.

The Garcias are not alone. Jackie Huerta has similar worries about her son taking social distancing protocols seriously.

Huerta is a single mother who currently works at Home Depot. Her son, Christopher, 11, attends Woodland Hills Academy. While Huerta works, her mother takes care of Christopher.

“Cases are going down but there’re still so many people that need to be vaccinated,” Huerta said. “Kids like to play. They like to be with their friends, close up, and I feel like they’re not so aware of social distancing.”

“I would want Christopher to go back to school so he could get to interact with other classmates but I do feel like it’s too early for him to go back to school,” Huerta said.

Huerta also said that if Christopher went to school for less than eight hours, it would be difficult for her to pick him off and drop him off at school because of her work schedule.

While some parents worry their kids won’t follow safety protocols, the Magaña family fears that sending their daughters back to school will compromise their health.

Maribel Magaña, 39, is a mother of two daughters. Candy is a third-grader at Carlos Santana Arts Academy and Kimberly is a 12th-grader at James Monroe High School in North Hills.

She manages a local McDonald’s restaurant where her husband, Bartolo, 41, also works as a cook. Their work schedules are the opposite of each other’s — when Maribel gets off of work, Bartolo clocks in.

The Magaña family is hesitant to send their daughters back to school, especially Kimberly. When Kimberly was 7, one of her kidneys failed and it changed their lives completely. In order to keep her healthy, Kimberly had dietary restrictions and had to follow strict treatment.

Kimberly received a kidney transplant in 2016. She needs to go to the hospital for frequent monitoring of her kidney function. Unfortunately, the pandemic has made their hospital visits challenging.

Before the pandemic, Maribel and Kimberly would take the Metro from North Hollywood to the Los Angeles Children Hospital. But with COVID-19, Maribel needs to protect Kimberly from contracting the virus. Maribel decided it was best to drive Kimberly to the hospital to reduce her chances of being exposed to the public.

“We don’t know how her body would react if Kimberly would get COVID-19. She could lose her kidney and that’s not a risk we can’t take” Maribel said.

Additionally, the Magañas struggles to find someone who could watch Candy since the hospital only allows one parent and one child. “If Kimberly gets COVID-19, it can be very crucial to her health. I can’t afford any of our family members getting sick” Maribel said.

On the other hand, the Altamirano family has different concerns. Rebecca Altamirano, 29, has concerns about the health measures as well as her son’s life in school.

Altamirano is a single mother and a college student who is currently unemployed. She’s currently living in her boyfriend’s family home.

She lost her job at Moorpark College when the campus closed due to the pandemic. Her son, Sebastian, 6, is a first-grader at Granada Hills Charter Elementary School. Before the pandemic, Sebastian was bullied by a classmate, who would take Sebastian’s belongings. Altamirano said the classmate once took Sebastian’s water bottle and drank from it. It turned out that the classmate had stomach flu, which spread to Sebastian via the shared water bottle.

Altamirano spoke to the teacher and school staff about the problem, but it didn’t stop the bullying. “If the school couldn’t have control over the bullying, how will they make sure the kids will keep their masks on?” Altamirano said.

She fears not only about her son contacting COVID-19 from other people in school but she worries Sebastian will be bullied again. Sebastian told his mother that he doesn’t want to go back to school.

These families want more information about how their kids can be kept safe. The information is still unclear to them about how in-person learning will be, leaving parents with questions.

Latino parents don’t want their kids to be victims of COVID-19. They want their kids to get back to school and enjoy their childhood in the safest way possible.