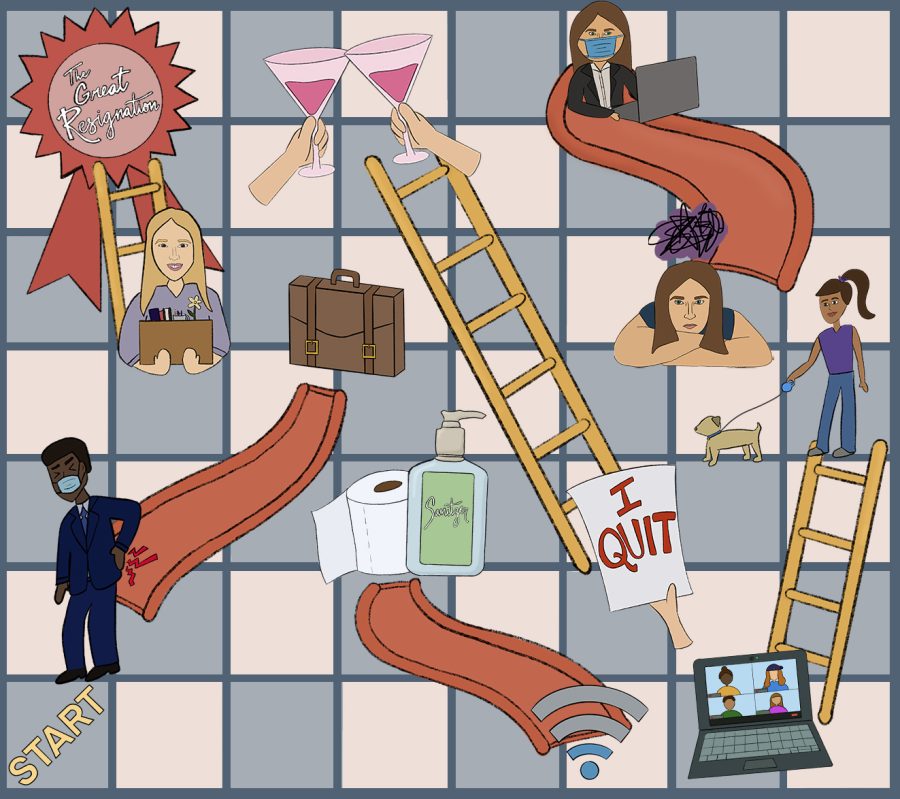

The Great Resignation makes waves in Northridge

September 20, 2021

Joyce’s Coffee Shop sits nestled between a printing store and comics shop, with bright yellow benches posted outside the cafe and the clinking of glassware bleeding onto Reseda. White, red and orange papers plastered on the front-facing windows ask customers to wear their masks in the store and enter around the back, but the faded “Help Wanted” signs stand out in both size and severity. It alludes to the struggle small and mid-sized businesses across the country have experienced throughout the last two years as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. With the danger of a highly-transmissible virus and various lockdowns, businesses like Joyce’s Coffee Shop have had to double down on retaining both their customers and employees.

“Thank God for the community because the community came and ordered from us,” said Michelle Blake Castro, the owner of Joyce’s Coffee Shop who took over almost three years ago.

The pandemic caused one of the worst recessions in U.S. history and completely transformed how we work. Where we once sat in cubicles and conference rooms, now we attend our meetings and classes from home.

Phrases like “Zoom in,” “socially distance” and “essential worker” flooded our everyday lives starting in March 2020. With the introduction of the Delta variant, a new problem arose: the wave of individuals quitting their jobs.

RELATED ARTICLE: 818 Night Market: Pandemic passion projects turned into local businesses

Dubbed “The Great Resignation” by Texas A&M professor Anthony Klotz in 2019, this trend of people leaving — or looking to leave — their jobs will have a notable impact on the economy, with small and mid-sized businesses feeling it the most. The U.S. Department of Labor recorded a total of 11.5 million workers who had quit their jobs in April, May and June 2021 alone. Microsoft’s recent Work Trend Index found that over 40% of the global workforce was considering leaving their employer, with out-of-touch leaders, exhaustion and a yearning to have flexible work being some of the proposed reasons for this voluntary exodus.

The pandemic left Joyce’s Coffee Shop without a consistent pool of employees, requiring Castro and her husband to run the ‘50s-themed restaurant with a small crew every day except Christmas. During the first mandatory lockdown in California that shut down indoor dining in restaurants across the state, the Castros paid employees $100 a day and gave them free lunch if they came in to help with indoor renovations that could otherwise not be completed while customers were in the building. However, most of the team did not return to assist with the renovation process. Even while following COVID safety measures, utilizing social media and implementing new changes to the menu as well as extended restaurant hours on select days, the diner has yet to hire a full crew.

“Nobody even called to say ‘are you back open?’” Castro said. “We’ve gone through eight or nine employees within the last month. It’s really frustrating.”

For business owners, “The Great Resignation” spells trouble. Workers, however, are using this time to find better work opportunities. Some people were able to work from home as businesses temporarily closed their offices to decrease the spread of COVID, which led many to realize that they could accomplish just as much in the convenience of their home. It allows them to save time that they would have otherwise spent on commuting and money on things like gas or lunch. Workers with children were also able to spend more time with them and engage in familial activities, while those without found it easier for them to take breaks for their health.

Essential workers experienced a much harsher reality. From long hours to unruly customers and COVID outbreaks, essential workers — many of whom continued to earn minimum wage in environments inadequate for protecting them from the virus — were faced with burnout and unsupportive management. This resulted in the departure of 650,000 retail workers in April 2021, according to data from the U.S. Department of Labor. Even as millions of these people lost emergency benefits on Labor Day, there is much reluctance toward returning to the workforce.

“[My job] was very demanding, and we were always staying late due to a shortage of workers and the tons of products that needed to be shipped out every day or stored,” said Sergio Ramirez, Jr., a second-year at CSUN who worked a warehouse job during the height of the pandemic last year.

In spite of the COVID-19 safety measures in place, the fear of contracting the virus still lingers in workers’ minds. “Working now is much different than at the height of the pandemic. For instance, even though masks are required, we still need to help guests who come in without them,” said Adrian Hawthorne, a fourth-year CSUN student that worked in the food industry in July 2020.

In the Northridge area, jobs are in no short stock. “Help Wanted” signs are plastered on local eateries while job hunting websites like Indeed bring up hundreds of open positions for part and full-time work. The resurgence of students on campus may help ease some of the burden these small and mid-sized businesses feel as a result of “The Great Resignation,” but the holidays are also approaching. Seasonal employees are now just as sought after as permanent ones, which means some businesses will have two times the amount of employees to hire before October, November and December. The holidays may mean more stress for store managers and owners, however, it also presents a new opportunity for increased business.

“This is hard work,” said Castro. “[But] we’re fighters [and] all we can do is give [people] a chance.”