Local activists fight for immigration legislation beyond DACA

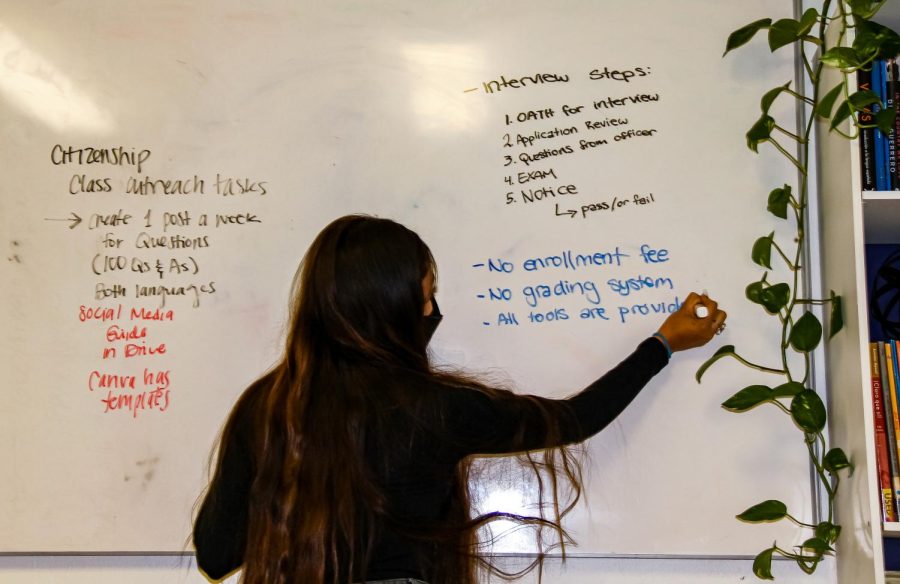

Dreams to be Heard President Zeltsin Herrera teaches a citizenship class on Jan. 22, 2022, in Los Angeles, Calif.

March 14, 2022

Chants of “America First” and “wait in line” were shouted during an anti-illegal immigration rally in 2010 led by then-city council member and former mayor of Santa Clarita Bob Keller, who proclaimed himself as a “proud racist” after advocating for “one flag and one language.”

Over a decade later, viral clips surfaced of the U.S. Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert shouting “build the wall” during President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address on March 1.

Phrases like these, along with constant questions like “how come they can’t come here the right way,” are things Patricia Robledo hears more often than she would like. After coming to the United States at the age of 1, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals recipient considers it the only place she would call home.

Robledo, along with her sister, were thrust into adulthood at an early age after her parents were taken away by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, a day that is forever locked in her memory. She is now an advocate for the legal citizenship of all undocumented immigrants through her work as a community organizing director at Immigo LA, an organization that often collaborates with CSUN activist groups such as Dreams to be Heard and Colored Minds.

Immigo LA is an organization founded by Magybet Mendez, an undocumented immigrant and community activist. Her organization, whose motto is, “Building power not paranoia,” focuses on supporting undocumented communities all around Los Angeles. Immigo LA provides services like legal consultations and green card assistance. She recently led a workshop called “Know Your Rights” which sought to educate undocumented immigrants who may have been victims of domestic abuse.

“I want to kindly remind everyone that this country was built off of immigrants,” Robledo said. “It’s not as easy as it sounds like ‘wait in line.’ These visas are not easy to obtain … if you are a victim of violence or there are problems within your own country, even asylum is not easy.”

A report from the University of Syracuse found that as of 2020, about 70% of asylum seekers end up having their claims denied. In order to qualify for asylum, the individual must prove that they are from a country that may persecute them or have a “well-founded fear of persecution” based on factors like race, religion or political affiliation, according to U.S. law.

The U.S. Department of State, which is the agency responsible for issuing visas for permanent residence, takes factors like financial status and criminal history into account when determining eligibility.

“If you are going to do it the ‘right’ way, you are going to end up waiting for 20 to 30 years in many cases,” Robledo said. “So when my parents came, they had to resort to other methods.”

Zeltsin Herrera, a CSUN student and the president of the club Dreams To Be Heard , believes that legislation should be passed that goes above and beyond DACA. Dreams To Be Heard is an organization that advocates for a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. Current paths for citizenship are limited to very specific avenues such as marrying a U.S. citizen.

Herrera teaches free citizenship classes to Spanish speakers, and her club also hosts fundraisers in order to support undocumented CSUN students.

Undocumented immigrants are still expected to pay taxes, and those who are not DACA recipents may struggle to find work as they have no work permit or social security number.

For Herrera it’s the small events in her daily life that make her feel tied down, whether it is being overly cautious at a red light, or something as simple as trying to create a GoFundMe page for a family friend who has died. Other members of Dreams to be Heard equate being undocumented to the feeling of panic a person gets when losing their wallet.

Certain crowdsourcing campaigns like GoFundMe require a social security number which many immigrants don’t have. Herrera explained that the reality for many undocumented immigrants is that one tiny mistake can change their whole life as they know it.

Herrera and Robledo both emphasized that the one restriction that affects them the most is not being able to see their families back home. Herrera’s mother had to experience a funeral over Zoom for her son who had died in Mexico. Returning to Mexico would have likely been a one-way ticket.

Many undocumented immigrants are currently being protected by DACA. This policy grants temporary protection to immigrants who entered the United States while under the age of 16. It also grants the recipient access to a temporary work permit. Recipients must renew their applications every two years, which costs $495. DACA does not, however, provide a pathway to citizenship.

There are several requirements when it comes to qualifying for DACA. According to the Department of Homeland Security, immigrants applying for DACA must have been under the age of 31 as of June 15, 2012, come to the United States while under the age of 16, and currently be enrolled in school, have completed high school, obtained a GE or been honorably discharged from the military. Qualifiers must also not have been convicted of a felony or significant misdemeanor.

DACA was created during former President Barack Obama’s administration in 2012. This program was put into law by an executive memorandum after legislation like the Dream Act failed to pass several times in Congress. The Dream Act was a proposed legislation that went further than DACA. The bill would have protected qualified individuals from deportation and would have also provided a pathway to citizenship.

Biden recently announced during his State of the Union address that his administration supports immigration reform and wants to provide a “pathway to citizenship for Dreamers,” a term often used for DACA recipients. This comes after his administration continued the Trump-era Title 42 public health policy, which was responsible for the expulsion of over 1 million migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“I just don’t get excited anymore,” Herrera said about immigration reform. “Just another one of their talks that’s going to get shut down. You contribute, you pay your taxes, why wouldn’t you want to give citizenship when that’s going to go right back into the economy?”

For her, one of the major roadblocks was that her family did not own a certain amount of land or property in Mexico. Herrea believes they were denied visas because officials did not believe that they had “something to go back to.” She advocates for citizenship for all as well as an easier path into this country.

“Why don’t we just come here legally? It’s definitely not because we’re trying to become criminals, it’s not because we’re trying to do anything illegally,” Robledo said. “It is because our families depend on it. It is because our parents are trying to seek a better future.”