Hard-of-hearing Matador stares down challenges on and off the field

April 29, 2022

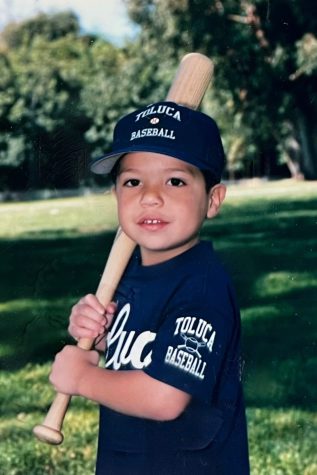

Under the lights on a Friday night in April, CSUN baseball player Gabriel Gonzalez stepped up to the plate in a must-needed run situation against UC Irvine. The home crowd yelled in support of the Anteaters. Gonzalez walked into the batter’s box and took a look at a few pitches until he found the perfect one.

Gonzalez, a redshirt senior, did what he does best: he sent a deep home run to right field to put the Matadors up. As he rounded the bases, he threw up the “I love you” sign in American Sign Language — something he has done every time he hits a home run to show respect to the hard-of-hearing community, which he and many others like myself are a part of.

At 13 years old, Gonzalez lost most of his hearing after being hit on the left side of his head by a baseball while playing in a summer tournament with his friends. The setting sun’s glare obstructed his vision, and when he was up at-bat he saw the pitcher throw, but lost sight of the ball as it approached him.

“I blacked out, but I told the coach that I was okay,” Gonzalez said. “I ran to first base, I threw up and had to go back into the dugout. I had cauliflower in my left ear, it looked like I just got out of a boxing match.”

Gonzalez did not realize that the situation was serious until Christmas of the same year. He tried on a new pair of Beats headphones, but he couldn’t hear a thing out of his right ear.

“On my right ear, I thought the Beats were broken because it sounded quieter,” said Gonzalez.

He was sure that they were broken, but his mom said they were perfectly fine. Gonzalez figured something was wrong, so he went to the doctor.

“At first, it was scary because they thought it could have been a tumor, and being 13 years old hearing you might have a tumor was very scary,” he said.

Although it wasn’t a tumor, he later went to a hearing specialist at CSUN to do a series of audio tests.

These hearing tests are often pretty simple. You are put in a soundproof room and asked to listen to the words coming out of the audiologist’s mouth. When you can hear the sounds, you press the clicker they give you.

Eventually, these sounds get quieter and quieter until it is almost impossible to hear. The hearing test checks how many decibels — which is the measurement that determines a person’s level of hearing — the person is able to register. Most people with hearing impairments, including myself, have taken these tests.

After taking the hearing test at CSUN, it was determined that Gonzalez had lost all hearing in his right ear, even though the ball had hit him on the left side of his head.

Hearing loss is an injury rarely seen in baseball, even from an athlete that plays it more often than others. However, Gonzalez did not let a life-changing moment affect the way he went about doing what he loves.

“So, I felt like [I] had never said, ‘Why him?’ And I got choked up because he was just like, ‘Now what?’” Sonia Smith-Kang, Gonzalez’s mother, said. “That has always been his approach.”

Gonzalez didn’t dwell on his hearing loss. His own sister’s situation wouldn’t let him, providing him with a model for how a person deals with a disability.

Breanne, his older sister, was born with a rare genetic disorder. She had a chromosomal deletion that caused challenges in her everyday life. Gonzalez would take care of her from time to time when he was young, so when he lost his hearing, he knew what to do.

Growing up he was able to help his sister whenever it was needed.

“I felt like he had a blueprint of what somebody who had faced challenges in her own right,” Gonzalez’s mother said. “He helped her out with her in her [Little League Challenger] program, which is a program that helps children who want to play the game of baseball.”

Being that adaptable type of person, he didn’t dwell on what happened and adjusted when school and baseball became a new experience.

“Things could be way worse than they really are. And you just have to adapt, find a way to overcome it,” Gonzalez said.

Before college, he participated in the Individualized Education Program, a program structured to ensure that students with disabilities’ needs are met. Every year, students have a meeting with their teachers to discuss their education plan for how to improve their next school year. Gonzalez would need a note taker, a seat in the front row, and closed captions on videos in his classes.

At CSUN, he is getting the same type of help through its National Center on Deafness, which supports roughly 150 students annually by providing services to hard-of-hearing people on campus.

Gonzalez also has help through technology like his hearing aid. He only wears it for a few hours a day, specifically during his classes or when he is at home. When Gonzalez is in public, he has a little trouble trying to focus on conversations, a situation that many other hard-of-hearing people have to constantly deal with.

“It’s also difficult for me to wear it in restaurants or places where there are a lot of people because you hear everything, you hear conversations from other people, so it’s kind of a struggle,” said Gonzalez. “It helps too much, to hear things that you don’t want to hear.”

Luckily for Gonzalez and so many who are hard of hearing, having a hearing aid allows someone to select what you want to hear. Gonzalez does this through a knob on his hearing aid that allows him to adjust the volume of the noises he receives.

“Sometimes, I do it to my mom, where I pretend like I can’t hear her when she is calling me to do something,” Gonzalez said while laughing. “If it’s something I don’t want to do I pretend like I didn’t hear her and she can’t get mad at me.”

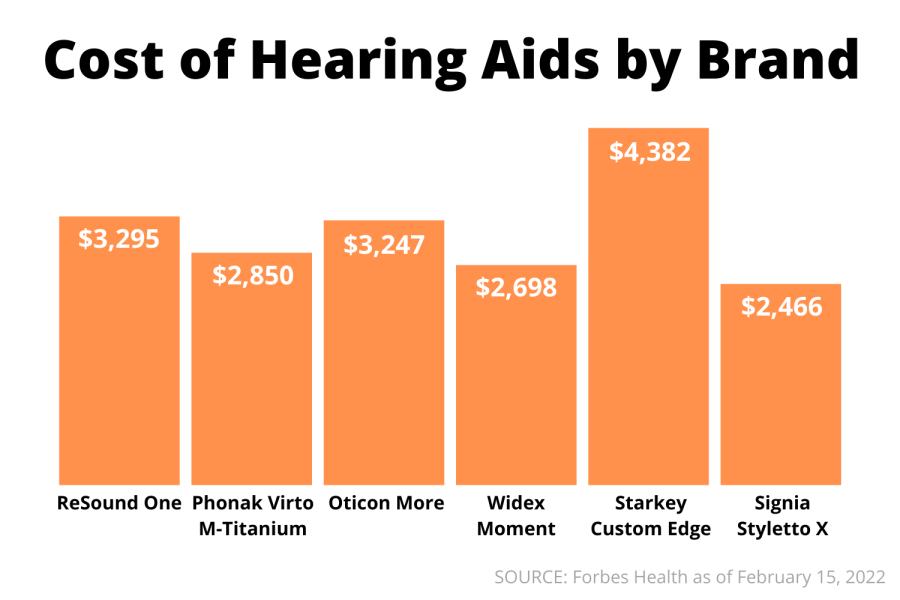

During his baseball games, Gonzalez does not wear his Phonak Hearing Aid since sweat damages the device.

Hearing aids are not cheap. The average cost of a hearing aid in the United States is around $2,000, according to Forbes Health. When purchasing a hearing aid, the price includes the technology as well as the professional services required to fit, maintain and repair the device. The price also depends on which type of hearing aid a person gets, with the bluetooth devices having a higher price.

While the hearing impairment did not affect his game performance, Gonzalez didn’t tell his coaches about it because he did not want to be treated differently, or use his disability as an advantage to get on the team.

Gonzalez’s coach at Los Angeles Mission College, Robert Marcial, found out about his hearing loss at batting practice one day when Gonzalez did not respond to him. For Marcial, it was not hard to adapt because one of his good friends was also deaf. He knew to make sure to speak to Gonzalez in his left ear.

Dave Serrano, head coach of CSUN’s baseball team, said he found out in the most interesting way possible.

Gonzalez missed multiple weight training sessions in the morning because he could not hear his alarm when he slept on his right side. At first, he made up excuses for his tardiness. Eventually the coaches called Gonzalez into the office, where he told them about his hearing impairment.

The coaches understood, then assigned Gonzalez a punishment for being late, like they would for any other player. Despite this, his coaches raved about Gonzalez’s leadership qualities.

Both Marcial and Serrano echoed the same sentiment that he was a leader both on and off the field.

“[He] was not only a leader [in the community], but by his actions. The guys would just follow him and then he would back it up,” Marcial said. “So, as much as he was a good teammate … he also produced on the field [and] off the field.”

Gonzalez’s time at CSUN almost did not happen. He was set on going to Jackson State University until Serrano, who heard about Gonzalez from a former assistant, offered him a tryout for the team.

“And once coach Serrano said, ‘You know what, we could give you a tryout, but I can’t guarantee anything,’ I said, you know what, that’s all I need,” Gonzalez said. “All I need is a chance.”

When Gonzalez made it onto the team, he knew that he had to work hard to earn the trust of his coaches and teammates because there were well-established players already on the team.

“Gabe was one of my favorite players,” Serrano said. “He’s been one of my favorite players since day one. He’s a baseball player, [and] what I mean by that is he knows the game, he’s very savvy in the game.”

During his first season, Gonzalez became injured, but he still learned and participated in any way he could. He was able to be a first-base coach for a couple of games, which got him interested in possibly coaching in the future.

Gonzalez has played 30 games this season as the designated hitter, hitting a clean .255 batting average with nine homers and 27 RBIs.

In his last season as a Matador, Gonzalez has thought about a life outside of baseball after college. He wants to be a firefighter so he can continue helping the community, but he’s not counting baseball out of his future just yet.

“You know, I always have [had] dreams and aspirations to [be] playing in the professional level. But, who knows what’s going to happen, where I’m able to sign in free agency or, you know, who knows?” Gonzalez said. “So, if this is my last year of baseball, I could be happy with that and live with no regret.”