20 years after Northridge earthquake, CSUN is ‘not just back, better’

FILE PHOTO – The 1994 Earthquake has destroyed Parking Structure C on Jan. 17, 1994 in Northridge, Calif.

January 17, 2014

It was 4:30 a.m., a time when most are sound asleep in their beds. Then, in an instant, the lives of those in the San Fernando Valley changed forever on Jan. 17, 1994 when the area was ambushed by 10 to 20 devastating seconds of a 6.7 magnitude earthquake.

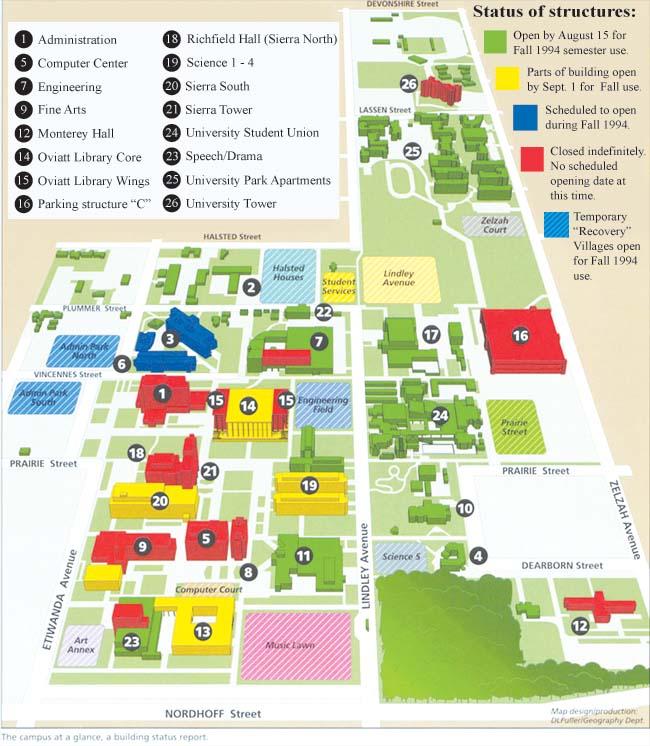

CSUN was gravely affected as well. The campus experienced catastrophic damage to the majority of the buildings as well as a total collapse of a parking structure.

When the earthquake struck, then-CSUN President Blenda Wilson felt the shock from an hour and a half away. When she drove to the campus, the first thing she saw was the parking structure, which was completely destroyed.

“I pulled over to the side of the road to compose myself for more, similar views of other campus buildings,” Wilson said. “What I viewed, however, were buildings that seemed modestly damaged but not razed. Unfortunately, that perception proved to be erroneous. Seismic damage is not visible to the untrained eye.”

The earthquake was one of the deadliest and strongest earthquakes to occur on a blind thrust fault — a compression created by the San Andreas fault — ever recorded in North America since the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, according to the Southern California Earthquake Data Center. Freeways, various apartment buildings, parking structures and office buildings around the San Fernando Valley were all severely damaged.

Earthquake casualties

The Northridge quake took the lives of 57 people, according to a report by the U.S. Geological Survey. The report also stated that more than 7,000 people were injured and 20,000 people were displaced from their homes.

Among those killed in the earthquake were CSUN students Jaime Reyes, 19, and Manuel Sandoval, 24. The families of Reyes and Sandoval told the Daily Sundial in a February 1994 article that a week had not passed since the students moved in to their first-floor apartment at the Northridge Meadows complex. The article said the earthquake caused the second and third floors to collapse, killing 16 people.

The geological survey said more than 40,000 buildings were damaged in Los Angeles, Ventura, Orange and San Bernardino Counties.

At CSUN, The University Tower apartments, Parking Structure C, the east and west wings of the Oviatt Library, the South Library and Fine Arts building were demolished by the earthquake. Of these structures, only the wings of the Oviatt Library were reconstructed, CSUN President Dianne F. Harrison said.

Structural improvements

Colin Donahue, CSUN vice president of administration and finance, said he came to CSUN in 1996 to assist in rebuilding the campus following the earthquake. With the damages costing approximately $400 million, Donahue believes CSUN has made significant changes that will ensure the safety of its students.

“We learned a lot from the Northridge earthquake and safety is the number one point of emphasis,” Donahue said. “We will never compromise on safety.”

In a February 1994 article in the Los Angeles Times, the Esgil Corporation, a consulting firm hired by the Cal State construction management office, expressed concerns that Parking Structure C did not meet the seismic codes claimed by the construction firm A.T. Curd Builders of Glendale.

“The difference in [past] earthquakes is that they usually move buildings horizontally,” Donahue said. “The vertical earthquakes are more dramatic.”

The joints of the building would have only absorbed horizontal but not the vertical shocks of the earthquake, according to the Curd Builders report. Esgil suggested joint connections would not have made a difference in saving the buildings.

Donahue said that in 1994, not all of CSUN’s buildings were structurally sound, especially in preparation for a 6.7-magnitude earthquake.

“A lot of the old buildings were concrete structures with sheer walls, “Donahue said. “We now use reinforced steel because it has a less chance of the columns buckling. Concrete has a lot of compression strength to handle weight while the steel bars have tensile strength to bend and elongate under pressure.”

All of CSUN’s buildings are in compliance with California codes according to the CSU Seismic Retrofit Priority Listings, a chart that lists which CSU structures need to be upgraded to be seismically sound in order to endure an earthquake.

Donahue also said the CSU has a process called seismic peer review, consisting of a private board of licensed structural engineer designers, assigned to work together to look deeply into the stability of structures and to see what can be done to make them stronger.

“Not just back, better”

Harrison disagrees with how some people perceive CSUN’s structural growth as a positive outcome of the earthquake.

“Within the CSU and certainly among many people in the community, there is this notion, a belief, a myth that after the earthquake that is why Northridge is so beautiful right now,” Harrison said. “I’ve heard elected officials make that statement, and a point of fact, the numbers of buildings that were rebuilt or reinforced was 14 percent.”

Harrison said the earthquake was a life-altering and tragic experience for many. She appreciated the stories of the community coming together.

“The things that came out of it was a renewal of commitment, a kind of loyalty and pride to the university and a desire to want to rebuild and open back up and continue serving students,” Harrison said.

Harrison was astonished by how Wilson handled the earthquake.

“She managed to reopen the university in two weeks,” Harrison said. “Being in a crisis and crisis aftermath is really when leadership comes to the surface or it doesn’t, and I think she displayed remarkable leadership. So much so that we are going to honor her in January with a permanent marker in a courtyard area on campus for her efforts following the earthquake.”

Wilson said what came after the earthquake was a group effort not just from those hired for reconstruction and cleanup, but from students, faculty, staff and the community as well.

“The typical distinctions of position, title and department became utterly irrelevant as everyone pitched in to do what he or she could,” Wilson said.

The former CSUN president said it was a remarkable personal experience for those who went through the aftermath of the earthquake, whether one was a professor teaching in an unconventional space or a student studying in a hard hat area.

“The great accomplishment of the faculty, staff and students was reopening the campus, mostly in temporary buildings about one month after the earthquake,” Wilson said. “If classrooms were not ready, professors held class outside, on the lawn, in their SUV’s, in their homes. The determination to hold class so that students could graduate on time fueled incredible creativity and adaptation.”

Regular status updates on the earthquake recovery were communicated through newsletters by Wilson. One newsletter said the university rented 300 temporary bungalows that would cost over $5.5 million for six months. In addition, classes were held in 25 off-campus locations, including LA City College, UCLA and Pierce College.

“Many expressed a wish to get back what they had lost,” Wilson said. “In response to that wish, we coined a phrase ‘Not just back, better’ to signal that the necessary repairs could and should be made in a manner that would improve what had been there before. I believe we accomplished that goal and that the beauty of the campus today is in part the result of the post-earthquake decisions.”

Students directly affected by the earthquake had the opportunity to dip into a $250,000 Earthquake Emergency Student Loan program provided by the CSU Chancellor’s office, according to a newsletter from the California Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators (CASFAA).

“The impact of the earthquake on the campus would have been an additional disaster had it not been for the Cal State system, which provided resources for the recovery, the mayor of Los Angeles, who set an example of speedy repair, and, at the national level, FEMA under President Clinton’s administration,” Wilson said. “The campus had no means of securing the $400 million plus that was spent to restore the campus completely.”

Associated Students (AS) established the Earthquake Related Emergency Book Voucher program, which cost $25,000. The program helped to alleviate the stress of purchasing needed class materials. The AS program provided $50 grants to students registered in six to 11 units and $100 grants to students registered in 12 or more units. A total of 264 students received grants, according to the CASFAA newsletter.

“Should another big natural disaster occur, I believe that AS will do everything possible to aid the students that we represent mentally, academically and financially,” said Sarah Marie Garcia, senator of education and chair of external affairs for AS.

Safety and precaution

Some CSUN students believe that students, faculty and staff are not prepared for the next big earthquake.

“I feel that structurally, CSUN is built to take a lot of force and has procedures as to how to handle [the situation] properly, but this isn’t transmitted to the students,” said Edgar Ramos, 23, an art major and member of Students for Quality Education. “I myself don’t know what I would do if a big one hit and many students probably don’t either. CSUN needs to take better initiative into teaching it’s students and displaying it for them as well because I personally, from history, feel worried living in Northridge.”

Harrison said students can get informed by participating in events like The Great ShakeOut, an annual exercise that attempts to prepare students for a major earthquake.

“We have emergency notices, we have staff who are trained, we talk to students to make sure that they sign up for our notification and alert systems and so forth, and I would say, yes, the tools are there,” Harrison said. “We have very carefully-thought-out plans and who’s supposed to do what and who’s supposed to go where that are in place.”

Harrison said in any disaster, something unanticipated may happen, but CSUN has put continuous effort in training employees on earthquake preparedness.

“Can you force people to drop and get under that table? No,” Harrison said. “But can we make sure that we have information that is available and has been posted electronically, sent to them in a text [saying] ‘here’s what you need to be doing?’ Yes.”

CSUN faculty reminisces

Part-time geography professor Robert Provin happened to be awake when the 1994 Northridge earthquake hit. Even 20 years later, memories from that morning are still fresh in his mind.

“It felt like a bomb went off,” Provin said. “I thought there must have been an explosion somewhere. Everything just hit like a bang.”

When daybreak hit, Provin rushed to campus to see what had happened. At that time, he was part of a group on campus that took inventory of damages, looking specifically at computer facilities.

“It was just spooky to go in there because it was dark, the ceilings had all collapsed, all the furniture, equipment, file cabinets, everything was all falling over,” Provin said. “You would find computers still running had fallen off of their desk…the monitors cracked open but the computers were still running.”

Geography professor Julie Laity, who has lived near Thousand Oaks in southeastern Ventura County since long before the earthquake, also will never forgot that day.”I remember being asleep and the house jolting and shaking very strongly,” Laity said. “My first thought was (to tell my young daughter) to run to her room. It was just a scary feeling.

We really hadn’t had an earthquake that was that strong in a long time.”

Laity seemed to find a silver lining despite all the damage that was done to the university.

“I think the campus is a better-functioning place now than it would’ve been had we not had the earthquake,” Laity said.

Contributing reporting by Lucas Esposito