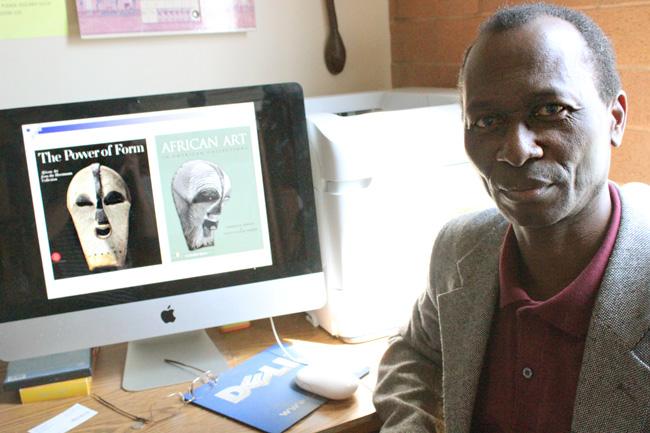

Photo by Araceli Castillo/ Daily Sundial

In summer 2011, Mutombo Nkulu-N’sengha started a Peace Institute in Camino, Congo to address the causes of violence and poverty in the area. N’sengha travels to Congo every winter and summer break.

The violence is defined by a pattern of human rights violations and conflicts between interreligious misconceptions. The Peace Institute consists of interreligious and intercultural backgrounds to eliminate pre-existing stereotypes in the community while promoting peace and nonviolence.

N’sengha, a human rights activist and CSUN professor of religious studies, typically asks the students at the Peace Institute in Africa questions in regards to addressing certain stereotypes of religion and other backgrounds.

“I am very much concerned about religious violence,” said N’sengha, president and founder of the Bumuntu Peace Institute. “We do have religious violence in our country and in other countries. You have that in the Middle East and in Africa.”

There are only about 50 textbooks at the university level in the new school N’sengha worked at in Congo, because of this mostly continues the development of human rights with public lectures and surveys of students’ dialogue.

“There are good new things we bring, but other stuff we coordinate, which have been there already,” N’sengha said. “The other advantage is I am coming from outside. Sometimes people have so many conflicts within the community that they need some kind of independent person to be kind of a breach.”

Throughout group exercises, students are able to interact and discuss issues and provide solutions by putting these situations in hypothetical scenarios, N’sengha said.

“What we do is help them understand the religion of the other to spell out the negative myth so they can learn to appreciate. It’s really about preventing future conflict,” N’sengha said. “That is why we mix interreligious dialogue and human rights issues to be sure that everybody has rights when it comes to employment.”

The growth of Islam created a rise in Christian fundamentalists, who are competitive with Christian beliefs among the community. Employment discrimination based on religion or what church a person belongs to are also current issues, N’sengha said.

“By avoiding having a religion of the state, you protect not only atheists but believers, who are members of churches, because there is a tendency to think ‘God spoke only to us,’” N’sengha said.

N’sengha is a teacher of global spirituality and interreligious and intercultural dialogue between young and old, men and women, ethnic groups and traditional culture and modernity.

“For the children we try to use traditional methodologies of reconciliation,” N’sengha said. “We teach norms about the UN and human rights, but it would be useless if you do not connect them to traditions. That is why we care about traditional values.”

N’sengha said religion in the southern part of the country was largely Christianized. Ninety-nine percent of the students are Christians — either Catholic or Protestants.

“People have been colonized and have been told everything indigenous is evil. Everything modern is good. Now what people copy is Hollywood movies. All the trash from the US is dumped to there and people think this is what is civilization,” N’sengha said. “So they lose their own traditional values.”

N’sengha encountered major issues in Congo among politics and families that are having difficulties with financial security in the economic crisis.

An overpopulation of approximately, 300,000 people live in each city. AIDs is a major health concern in Congo that has spread and caused a depopulation growth, according to N’sengha.

The institute also focuses on empowering women to enter higher educations and employment. Women excel to the high school level, but less women are attending colleges, N’sengha said.

The Peace Institute also works with existing institutions to help promote peace and give scholarships to students who cannot afford tuition costs and school fees. The institute receives about $8,000 a year, including outside donations.

“Many students drop out because they don’t have that kind of money. There’s no middle class. There is either poor or very poor and one percent rich,” N’sengha said. “What we do is recruit people who are from poor families and who are brilliant, give them scholarships and train them. We call it the ‘Obama Academy.’ My goal is to have at least 100 people in the scholarship program by next semester.”