When the Storm Came

Mike Boundy

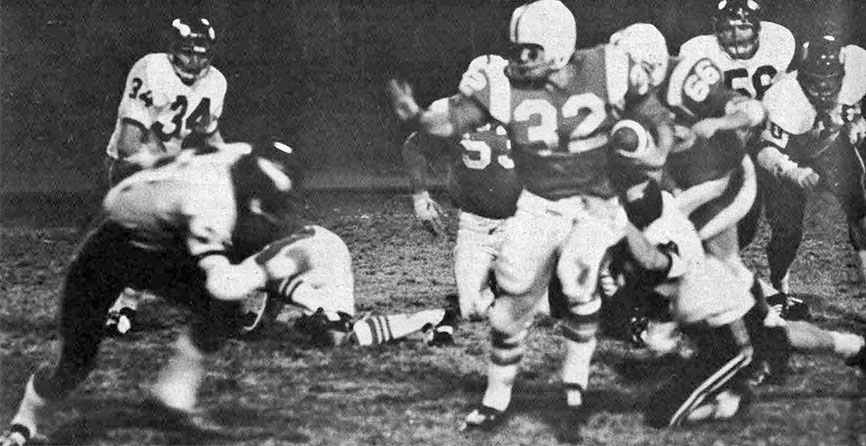

Archival Sundial photo during the Valley State football game vs. Portland State University on Saturday Nov. 2, 1968.

February 27, 2020

CSUN today is known as a diverse campus with some of the largest ethnic studies programs in the country, but it is a far cry from what the campus looked like 52 years ago. Black students accounted for less than 1% of the student body in 1968, even though the campus experienced an increase in Black students from less than 30 to 200, according to Sundial archives.

“The (Black) students were not well received by administration in any capacity,” said Aimee Glocke, associate professor of Africana studies at CSUN.

The late 1960s was a politically-charged time not just on campus, but in the United States as a whole. Protests such as the Black Power Movement and the anti-Vietnam War movement simmered in the background of CSUN — then known as San Fernando Valley State College — heading into a new school year. Then in early November, it all came to a boiling point.

When Valley State football player George Boswell, a Black student-athlete, was kicked by his white coach Don Markham on the field in early November 1968, it marked the tipping point of racial tensions and sparked a movement that would change the campus for years to come.

“Change had to happen … Black people were sick and tired of fighting for their rights and being beaten, or being murdered,” Glocke said. “The Black students were like, ‘Enough is enough. We’re going to take what we deserve.’”

The Black Student Union met with Athletic Director Glenn Arnett on Monday, Nov. 4, 1968 with the goal of discussing “the entire philosophy of Valley State’s athletic program” along with the BSU’s complaints against Markham, according to Sundial archives. During the meeting, Arnett allegedly told student leaders that they should talk to then-president Paul Blomgren. The student group then marched to the administration building with a list of demands and occupied Blomgren’s office for four hours.

The demands included a calling for the investigation and termination of Markham, expansion of the EOP program, creation of ethnic studies, and the recruitment of minority instructors. Blomgren initially signed and agreed to the demands, however he recanted as soon as the students left the building and claimed that he felt threatened to sign, according to Sundial archives. Felony warrants were immediately issued for all Black students involved in what is now known as the Storm at Valley State.

Another series of protests occurred in early January of 1969, the first of which resulted in students being beaten by police with batons. Then-BSU leader Jerome Walker recalled in the “Storm at Valley State” documentary that after a while of being beaten, “They just couldn’t hurt me anymore.”

A rally was held on campus the next day although the administration had declared a state of emergency, in which there was no assembly allowed. It went on as planned and 275 people were arrested as a result, according to Sundial archives.

Negotiations between BSU and the administration picked back up almost immediately following the protests. After 12 days, a resolution was passed. Most of the original demands were eventually agreed to, the most significant being the creation of the ethnic studies, including the Africana studies department.

“Ethnic studies were the only disciplines that were birthed out of protest, which sets us up on a very different trajectory as a campus,” Glocke said. “We are a constant reminder to administration that they are inherently racist and embrace white supremacy.”

Although there were many events and attitudes that ultimately led to the Storm at Valley State, it was a football game that seemed to set everything in motion. It was yet another example of sports serving as a backdrop for change in the face of backlash from a white audience. Not unlike Muhammad Ali’s stand against the draft, not unlike Tommie Smith and John Carlos each raising a black-gloved fist during the national anthem at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, and not unlike Colin Kaepernick taking a knee. George Boswell unwillingly became a key catalyst in making CSUN what it is today.

“The Black athletes definitely believe that it is an art form that they’re doing, but it also has to have a purpose and function,” Glocke said. “In general society, because there tends to be more of a Euro-centric lens, it’s always like, ‘Sports are supposed to be neutral.’ So when you get Black athletes playing sports in these Euro-centric spaces, you’re going to see the Black athletes be who they are.”