The silence of college coaches is deafening

June 3, 2020

It has been over a week since the brutal and inhumane murder of George Floyd at the hands of four Minneapolis police officers sparked outrage and protests nationwide. Athletes from all levels have taken to Twitter to voice their frustrations and some, such as former Golden State Warrior Stephen Jackson, have joined protesters on the ground.

Stephen Jackson with just about the most powerful words I’ve ever heard pic.twitter.com/7guc6O4T6W

— Jon Krawczynski (@JonKrawczynski) May 29, 2020

CSUN alumna and women’s basketball star De’Jionae Calloway tweeted her thoughts and fears in response to a TikTok remix of the wipeout challenge that was made to bring awareness to Black Lives Matter. CSUN athletic director Mike Izzi released a statement calling out the “disparities that caused the loss of George Floyd’s life.”

“The recent events in this country display the continued presence of and inequality in America,” Izzi said in the statement. “CSUN athletics must be clear in our stance that this cannot be tolerated.”

There have been a few notable Division I football and men’s basketball coaches, such as Jim Harbaugh, Mario Cristobal and John Calipari, who seem to understand that this moment is much bigger than any sport.

Outside of a few other notable examples, however, there has been eerie radio silence from the head coaches across all sports, particularly those — such as football and basketball — that benefit heavily from Black athletes.

“The reality of it probably is that they don’t have the guts to step out and put that opinion out there because there are going to be people who disagree with it,” said Zach Smith, former wide receivers coach and recruiting coordinator at Ohio State. “This country is so screwed up that if you step out and say something in support of this, you’re going to get backlash.”

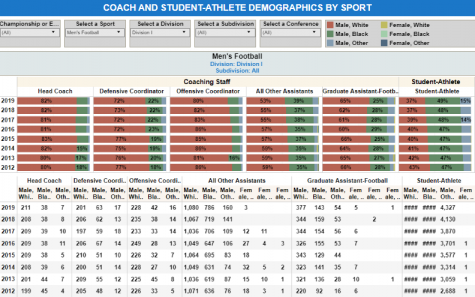

According to the NCAA demographics database, the number of Black college coaches is disproportionate to the amount of Black student-athletes. Eighty two percent of Division I football head coaches are white, despite the fact that almost half of Division I football players are Black.

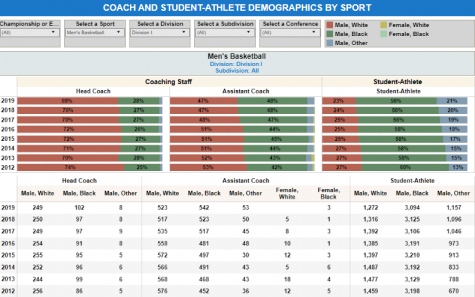

In men’s basketball, 56% of Division I players are Black but over two-thirds of head coaches are white, according to NCAA.

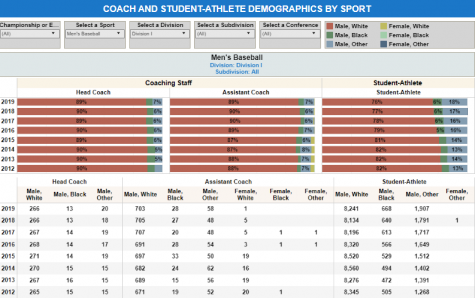

Baseball, the sport that champions Jackie Robinson for breaking the color barrier in 1947, is not exempt from the racial disparity. Six percent of baseball players and 4% of head coaches in Division I are Black. Out of 10,816 Division I baseball players, only 668 are Black. Clarence Carter III is one of them.

When Carter was being recruited to play for Bethune-Cookman University, he was given the same pitch many student-athletes hear: “We’ll treat you like family.”

Smith is familiar with the common phrase, although he never used it while recruiting because he sees it as meaningless.

“I’m not going to tell you that you’re going to be like family or you’re going to be like my son because that’s all bullshit,” Smith said. “I’m going to show you that I care about you and then you’re going to show me you care about me. We’re going to build a relationship based on trust.”

Carter saw through the facade almost as soon as he got on campus at Bethune-Cookman. He sees it even more clearly now that coaches across the nation, including his own, have been silent about police brutality.

“Waking up every day, I got to leave and I got to worry about a cop,” Carter said. “If I get pulled over, I got to pray to God I make it home. And you can’t say nothing?”

He warned coaches in all sports that if they don’t start speaking out in support for their Black players, they may not reap the benefits of their talents much longer. Rather than committing to colleges in Alabama, Texas, or Tennessee, Carter suggested Black recruits may and should start looking at historically Black colleges and universities, such as Howard University or Florida A&M University.

After his redshirt senior season for Bethune-Cookman was cut short by the COVID-19 pandemic, Carter entered into the transfer portal. He said that he is keeping an eye on which programs are speaking out and which ones aren’t.

“This is how we’re living every day. On edge, because we’re afraid our lives can be taken,” he said. “If a coach cannot see that and understand that, then that’s not my place or home. That’s not where I belong.”

To all coaches who have yet to speak out: by not publicly supporting your Black players, you have shown that you care more about appeasing your fans and keeping them comfortable than making your players feel seen, heard and valued.

You haven’t said anything, but we all hear you loud and clear.