It’s not just the NFL: three Hart High School alumni advocate for removing Native American imagery

Hart High School, sets out to address Native American mascot “Indians” after students create a petition.

August 11, 2020

When Julia Estrada was entering her freshman year at Hart High School in Santa Clarita, she was embarrassed. When Estrada, who has Arapaho and Comanche heritage and grew up going to pow wows, told her family that her school’s mascot was an Indian, they were in disbelief. They couldn’t believe that Santa Clarita, the area they lived in, embraced a mascot that mocked their culture.

Hart is far from a standalone case. There are around 2,000 sports teams in the U.S. that have a Native American mascot, according to a journal article published by professors from Springfield College, Harvard University and the University of Michigan on June 8.

While some of the more high profile uses of Native American imagery are in professional sports such as the Kansas City Chiefs and the Washington football team in the NFL and the MLB’s Cleveland Indians and Atlanta Braves, the majority of Native American mascots are associated with schools.

“Seeing that tokenization of your people is hurtful,” said Pamela Villaseñor, a citizen of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians. “It continues to play into this pressing issue of misrepresentation … people fail to see the connection between racist mascots and racist iconography and the continued damages to communities.”

The journal article pointed to four 2008 studies conducted in Arizona on Native American youth in the state. It was found that Native American mascots are harmful to the psychological well-being of Native American youth, regardless of whether or not they are perceived positively.

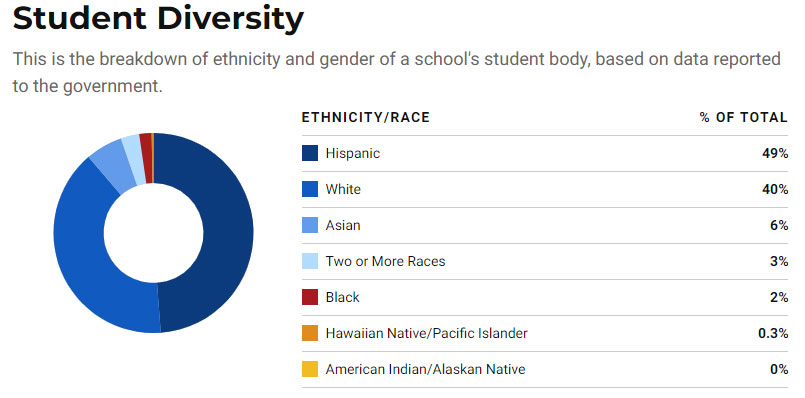

Throughout her four years as a student at Hart, Estrada witnessed a headdress being passed around at football games, whooping calls being made by her classmates at several different sporting events, teepees used during rallies and her school principal using the phrase “proud to be an Indian” even though Native Americans make up less than 1% of the student population reported during the 2017-2018 school year, according to US News.

“Ignorance is kind of validated with our mascot,” Estrada said. “We don’t learn enough about Native culture for people to be educated enough to learn that wearing a headdress at a football game is ignorant and doing Indian calls is ignorant, because we are an existing group of people that a mascot kind of portrays as almost mythical.”

While Estrada would talk about how uncomfortable she was with the Indian mascot individually with people, she never publicly challenged the mascot’s status to administration because she noticed they were wary of even addressing the issue whenever it was previously brought up. When she graduated from Hart this year however, she saw an opportunity to speak up.

Her friend and classmate, Grace Gooneratne, started a petition on change.org which simply read “Retire Hart High’s ‘Indian’ Mascot.”

“Our country’s treatment of Indigenous people, subjecting them to different kinds of violence, destroying their culture, and forcing them off their land has led to current day problems like mass impoverishment, lowered access to education, and inadequate healthcare,” Gooneratne said in the petition’s description. “The use of offensive stereotypical images of Native Americans for school mascots only perpetuates these issues.”

Estrada joined Gooneratne along with another friend, Kathryn Supple, and made social media accounts to promote the petition and raise awareness about the history of Native American mascots. In the wake of Black Lives Matter protests and the corporate pressure from Nike and FedEx on the Washington NFL team to change their team name, which was a slur used against Native Americans, Estrada felt it was the perfect time to put pressure on Hart’s administration.

Their petition has over 8,200 signatures as of Aug. 11.

Hart’s school board took notice of the petition and reached out to Gooneratne, Estrada, Supple and the Fernandeño Tataviam band to discuss the mascot.

“We’ve all been paying close attention to the calls for social justice, the protests and the question of Native American mascots,” said Jason d’Autremont, principal of Hart High School via email. “I am especially attentive to instances where students share that they feel marginalized for any reason. I’ve had a number of conversations with the authors of these petitions and I appreciate their advocacy. It has encouraged me to understand more about this issue.”

D’Autremont announced on Aug. 10 that Hart would no longer allow the use of headdresses, teepees, or whooping calls at school events and that a wooden Indian statue in the school’s Associated Student Body office had been removed. The Hart Union High School District Board will reportedly vote on the fate of their Indian mascot at a meeting in December.

Estrada said that while she appreciates d’Autremont and the board’s cooperation, she feels the administration should implement an enforcement plan for the new rules.

“I really hope that our district board remembers the words of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians and the students present through the entire process,” Estrada said. “And decide to change the mascot in December.”