Pulitzer Prize-winning CSUN alumni return to campus to share their stories

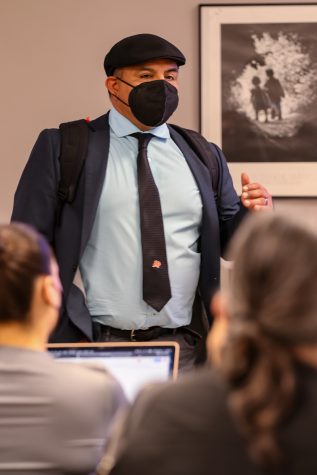

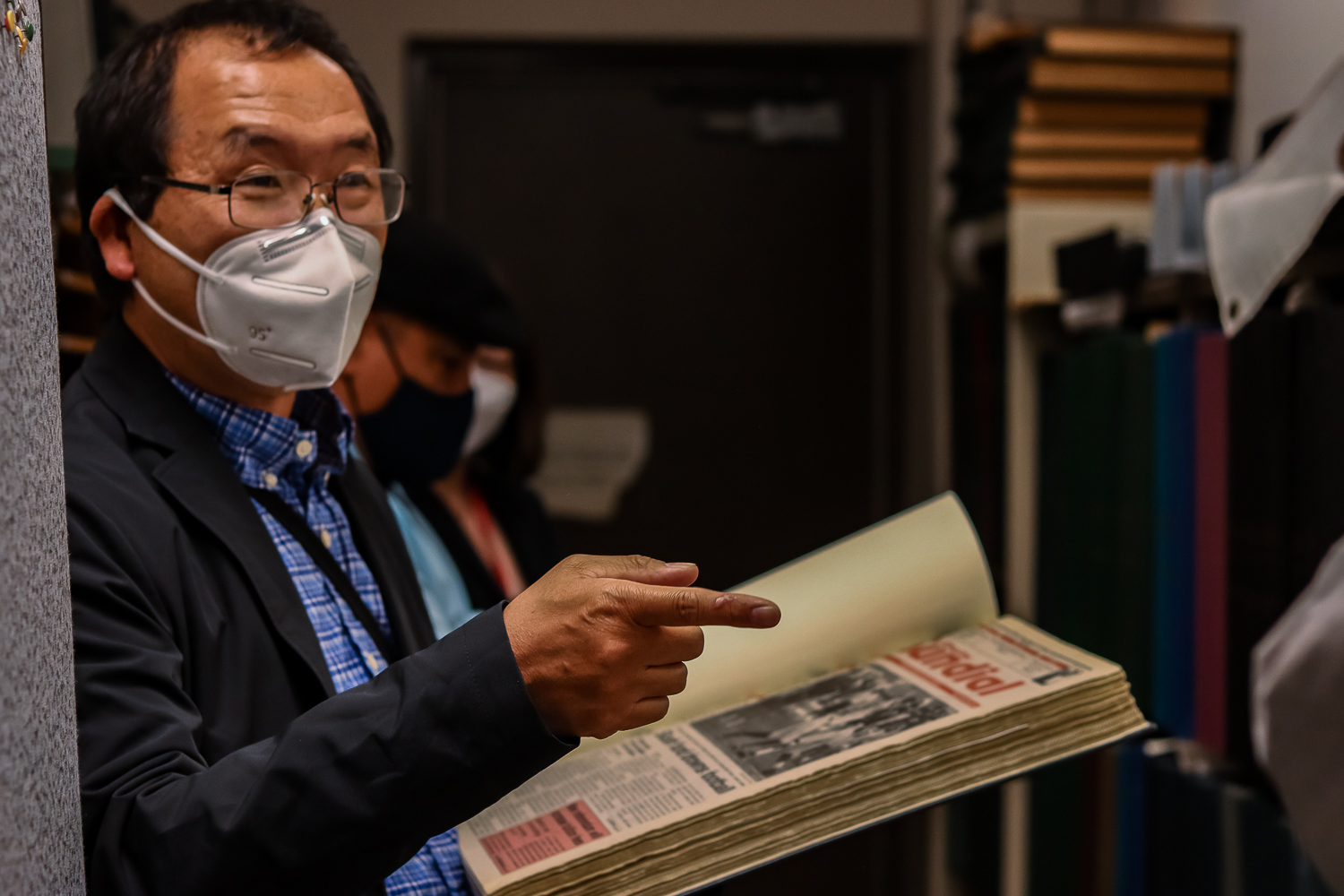

Pulitzer Prize winners and CSUN alumni Julio Cortez (left) and Ringo Chiu take time out of their busy schedules to visit the CSUN journalism department. The two roamed the halls of the place where they once took journalism classes and shared their nostalgia as they spent the day at the CSUN campus in Northridge, Calif., on Wednesday, Feb. 16, 2022.

February 21, 2022

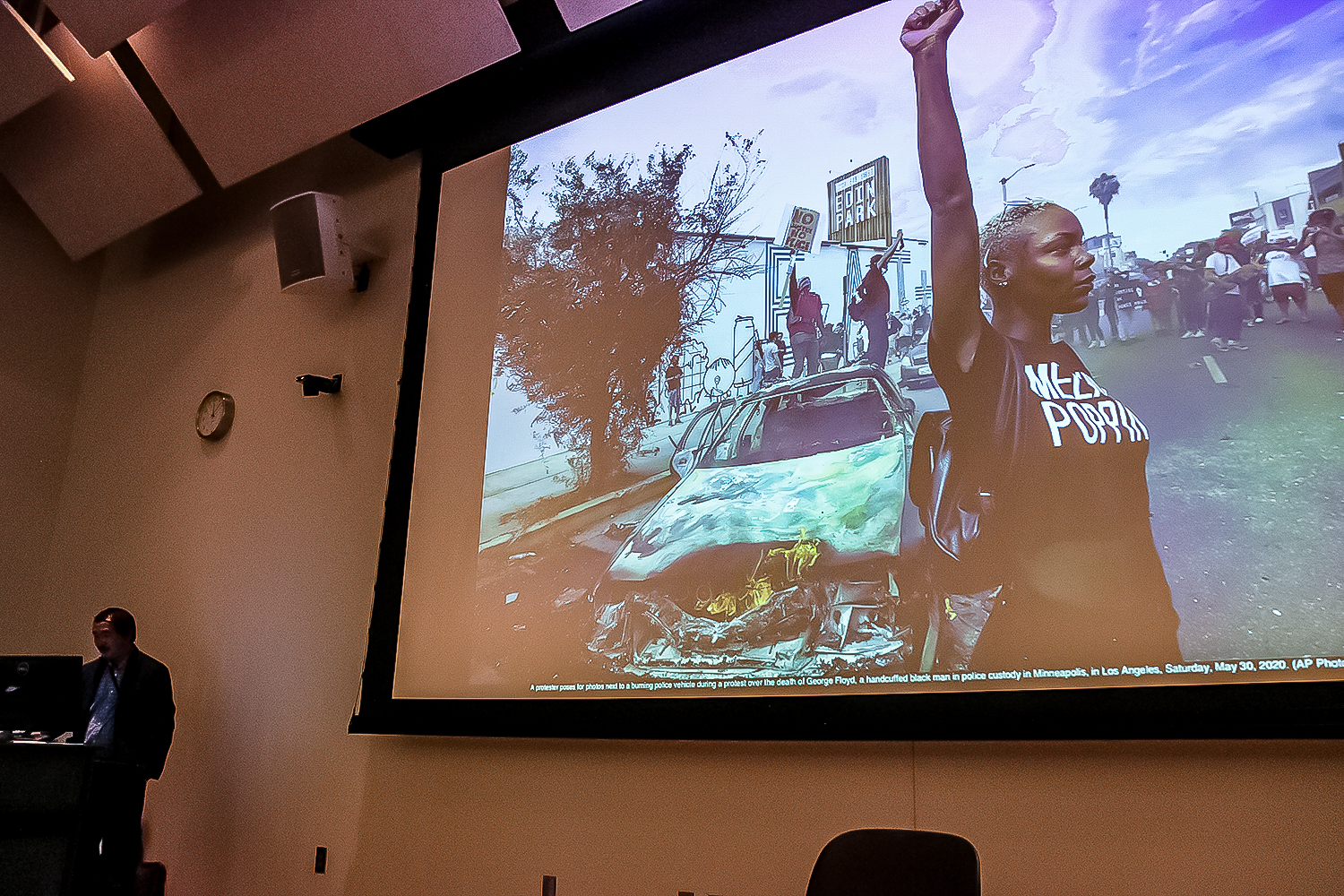

As pictures popped up on the projector in Kurland Lecture Hall, students stared at burning buildings, long lines of police officers emerging from blue smoke, and a protester protecting a police car.

Two CSUN alumni captured it all in the summer of 2020 and scored the most prestigious journalism award in history for it.

Julio Cortez and Ringo Chiu, with a team of 10 Associated Press photographers, recently won a Pulitzer Prize for breaking news photography. Their photos captured moments of the Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The two returned to CSUN on Feb. 16 to discuss their award-winning pictures.

“It’s surreal [being back at CSUN] because I spent so much time here,” Cortez said. “But it also feels like it was a split second [ago].”

Before becoming Pulitzer Prize winners, Chiu and Cortez were CSUN students. They both worked for The Sundial in the early 2000s, and Cortez helped revitalize El Nuevo Sol with another classmate of his, Sal Hernandez. Chiu graduated in 2001 and Cortez followed five years later.

They both went on to work for major publications. Cortez is now a staff photographer for the AP’s Baltimore team and has covered stories ranging from the Olympic Games to the post-Boston Marathon bombing manhunt.

Chiu, who holds the position of chief editorial photographer at the Los Angeles Business Journal, has worked freelance for a number of publications that include Reuters and the Los Angeles Times.

Cortez had been watching the events leading up to civil unrest in Minneapolis after the murder of George Floyd. On May 28, he received a call that he needed to fly out to Minnesota immediately with the AP’s New York City staff photographer John Minchillo.

With his luggage, camera equipment and a bulletproof vest, Cortez traveled to Minneapolis, where he would later witness one of the most important events of this decade.

Only two days later in Los Angeles — roughly 2,000 miles away from Minneapolis — Chiu was at a demonstration following the death of George Floyd. He was working as a freelance photographer for the AP when he captured the image of a protester next to a burning police vehicle with her fist in the air. This shot later became part of the Pulitzer Prize-winning package of pictures.

The protest in Los Angeles was initially peaceful, but turned violent as it went on. Chiu expected it to escalate, especially when protesters began burning police cars. While attacks on journalists are not as common in the United States, being shot with rubber bullets by the police or assaulted by protesters became Chiu’s main concern.

“Since that time, I [have paid] more attention because I feel myself [becoming] the target of police and demonstrators,” Chiu said. “Now I wear the vest.”’

For many photojournalists, capturing the perfect shot can be both exciting and dangerous. Journalists faced a record 438 physical attacks in 2020, according to a report by the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, an organization dedicated to protecting journalists’ First Amendment rights. About 91% of these assaults occurred while they reported on the nationwide George Floyd protests, and law enforcement officers were responsible for 89% of those attacks.

“Safety has always been an issue across the world,” Cortez said. “All of a sudden, we started seeing all these attacks coming in domestically. It’s different because it’s our friends who are getting beat up.”

Chiu himself was even attacked while reporting. While covering the Black Lives Matter protests in Los Angeles, Chiu was shot five times with rubber bullets by police. He still has a scar from one of the bullets on his lower abdomen, which he believes was fired at him intentionally, prompting Chiu to file a lawsuit against the Los Angeles Police Department.

“Every time I cover protests now, I get uncomfortable,” Chiu said.

Moments like these were what made 2020 the most difficult year for him to report.

While covering the U.S. Capitol Insurrection on Jan. 6, Cortez watched one of his AP team members get pushed and dragged from the front railing. Cortez tried to de-escalate the situation by grabbing the photographer, but members of the crowd were becoming increasingly violent. The entire situation was captured through a camera attached to his helmet.

“I had night terrors for months after January sixth,” Cortez said. “Somebody’s split-second move could’ve been fatal at that moment.”

Despite the dangers Cortez and Chiu encountered, they still marched on in pursuit of those perfect, Pulitzer-winning shots.

“We have to decide: do [we] wanna take a risk and get a good photo?” Chiu said. “I chose to take a risk to get the good photo.”