This year marks 40 years since the first Armenian language course at CSUN was offered. Today, the Armenian Studies Program (ASP) offers 10 courses. CSUN is home to the largest Armenian student population out of the entire California State University system – admitting about 450 Armenian students annually.

Although the program has been around for 40 years, it has struggled to keep its footing.

The program was established in 1983 when the Armenian Students Association (ASA) began offering and funding their own Armenian language courses. Their teacher was Hermine Mahseredjian – a high-school counselor and psychologist who volunteered her time to teach at CSUN.

At the time, the ASA was raising money to pay Mahseredjian, but fell short on their promises due to lack of funding. They had to fund their own classes due to CSUN’s lack of interest in funding the program, according to an archived Daily Sundial article.

“We have to concentrate on the more important languages, such as those from western civilization and current trade languages,” former chairman of CSUN’s foreign languages and literature department Alvin Ford said, who was not convinced of the language’s relevance.

Armenian immigration to the United States spiked from the 1970s to 1990s due to the Lebanese Civil War, the Iranian Revolution and the collapse of the Soviet Union. The influx of Armenians also increased their attendance at CSUN – creating a demand for learning and preserving the Armenian language.

“I understand where he was coming from, but he was shortsighted,” said Vahram Shemmassian, director of the ASP, in reaction to Ford’s statement.

Shemmassian is the only tenured professor of the ASP. He took over in 2006 after Mahseredjian stepped down, according to CSUN’s Digital Collections.

Academic programs in Armenian studies

The ASP is a part of the Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures Department, which is a part of the College of Humanities.

Students can major or minor in Armenian studies, choose a concentration in Armenian with a liberal studies major, or they can train to become a credentialed Armenian teacher with the liberal studies program’s Integrated Teacher Education Program.

Shemmassian believes the program has many uses, ranging from local to national. He says there is currently a high demand for Armenian language teachers within the Los Angeles Unified, Glendale Unified, Pasadena Unified and Burbank Unified School Districts. He also mentioned the knowledge of the language being useful in law, healthcare and governmental positions.

Students have different reasons for enrolling in the program. Lily Chakrian is a senior double-majoring in business administration with an emphasis in real estate and honors in business. She is also double-minoring in Armenian studies and marketing.

She is also the president of the CSUN Hidden Road Initiative, a nonprofit that provides educational and leadership opportunities to students living in remote villages in Armenia.

Chakrian grew up with the Armenian community, but wanted to expand her language skills and share her culture with others.

“Being able to spend some of my time in university furthering my knowledge to ultimately spread historical information to others who are unaware was the main reason I chose an Armenian minor,” Chakrian said.

Chakrian said she had never been able to read or write Armenian – a skill she eventually learned in Armenian 101, which teaches elementary Armenian.

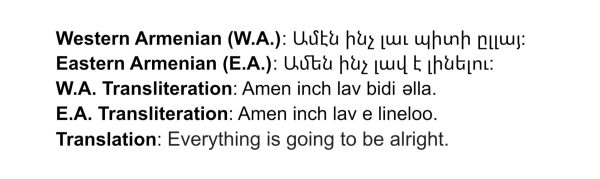

The language courses offered by the program are in Western Armenian, the dialect primarily spoken in Turkey, the Middle East and communities in the diaspora. Eastern Armenian is primarily spoken by Armenians from Armenia, Western Azerbaijan, Russia, Georgia and Iran.

The standards of each dialect have their own orthographic and phonetic differences, and the colloquial dialects of both standards can also vary. For example, Armenians from Turkey may use Turkish words within their colloquial speech. Armenians from Armenia will have a greater influence from Russian – although it is not uncommon for them to also use some Turkish words.

Armenian comedians have even made sketches on the differences in colloquial dialects.

The differences between the two dialects have created some resistance to taking CSUN’s classes within the Armenian student population, because many speak the Eastern dialect.

Chakrian grew up with a father from Armenia and a mother whose family is made of Armenians from Lebanon, so she had exposure to both dialects.

“I grew up speaking both Eastern and Western Armenian, so adjusting to the Western Armenian background here at CSUN was not as difficult for me as it seems to others who have expressed their difficulty adjusting,” Chakrian said.

Despite the amount of Armenian classes offered by CSUN, Shemmassian said there is a lack of enrollment. Due to this, the ASP allows majors or minors to find substitutes for its required courses.

Varant Tchalikian is a fifth-year computer information science major. His major requires a minor, so he chose Armenian studies. Tchalikian said although he enjoyed his language class with Shemmassian, one of his other classes, Equity and Diversity in School, was canceled due to low enrollment. Only he and one other student enrolled in the class.

For the future of the program, Shemmassian was adamant about preparing a replacement in advance and not letting the program die.

“Whenever I decide to leave, I want to make sure someone replaces me,” Shemmassian said. “I don’t want this to happen to the Armenian program.”