The speed limit: 65. The car speed: 80. Police lights begin the strobe of red and blue as a siren hollers and the 80-mile-an-hour car is directed to the side of Interstate 10 leaving Phoenix. As the cop approaches, he sees a man who appears to be Latino. The man rolls down the window, and the officer crinkles his eyebrows. “You were speeding. Now, show me your papers, please.”

This hypothetical scenario may become the reality of all Latinos in Arizona with the “Show me your papers” provision of the state’s infamous Senate Bill 1070 law in effect since Sept. 18.

SB 1070 passed in the spring of 2010 and has since been at the top of many political discussions as to whether demanding papers from suspected undocumented immigrants is a new form of racial profiling.

Much confusion has arisen over the law with many people believing that cops can approach anyone and demand citizenship documentation without reason.

According to Arizona legislature’s Senate Bill 1070, immigrants are required to carry registration documents at all times, but an officer may only demand proof of citizenship during other “lawful contact.” The bill states that during any lawful contact made by law enforcement officials where suspicion exists that the person is in the U.S. illegally, an attempt shall be made to determine the person’s immigration status.

Origin of the Arizona laws

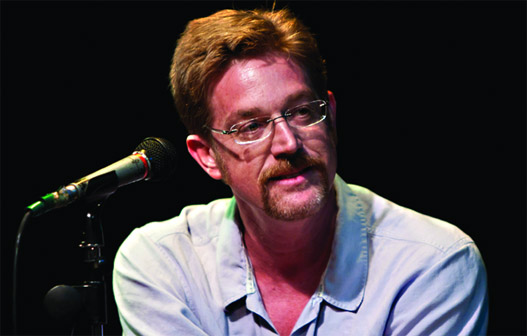

Jeff Biggers, an author, journalist and historian who is speaking at CSUN Tuesday, wrote his latest book about contradictions, myths and facts of Arizona’s history and civil and labor rights conflicts. “State Out of the Union: Arizona and the Final Showdown Over the American Dream” criticizes SB 1070 and what Biggers calls the “Arizonification of America.”

“The media flooded viewers with the images of gun-toting anti-immigrant extremists including neo-Nazis, Tea Party yahoos and fringe political figures,” Biggers said. “But there is another side of Arizona, like any other state, and an inspiring legacy of resistance that has fought back through extraordinary movements, campaigns and struggles, helped to shape the national liberal and conservative agendas and will ultimately have a more lasting impact on our history.”

After a rancher was shot in the borderlands, Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer and former Arizona State Senator Russell Pearce “manufactured the immigration crisis for a larger state’s right political agenda,” claimed Biggers, who was raised in Tucson, Arizona. He also said Brewer’s poll ratings soared after her crackdown on immigration, even though “rates of violent crime along the Mexican border had been falling for years.”

Another controversial Arizona law passed in May of 2010 was Brewer’s approved ban on ethnic studies classes, House Bill 2281. The bill states public school students “should not be taught to resent or hate other races or classes of people,” which has singled out Chicano/a studies as an example of this.

The bill restricts courses that “promote the overthrow of the U.S. government, promote resentment toward a race or class of people, are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group, and/or advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals.”

Banning an identity

Professor Rudy Acuna sipped his coffee, set down the Freudian Sip cup and lifted his hands to the rim of his glasses. Acuna, the founding chair of CSUN’s Chicano/a studies department, removed the black frames from his face and exposed his emotional eyes. He described his struggle to keep only the truth in the minds of students.

“I’ve been banned before and lost a job because people said I was lying about the U.S. invading Mexico,” said Acuna, 80. “Every document of the time said the U.S. did invade Mexico. They want to change the truth, and I don’t want to change the truth.”

Acuna said the biggest danger is the escalation of Arizona-inspired laws into other states like Alabama and Pennsylvania, and he hopes students go to Biggers’ appearance on campus and understand the severity of the situation.

“This is real, and students don’t think it’s real,” Acuna urged with concern. “I hope they go listen, get encouraged and go to Arizona and other places with injustice and get involved in changing things.”

Grace Castaneda, a senior political science major, is a member of the M.E.Ch.A (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan) club at CSUN, or Chicano/a Student Movement of Aztlan, which is one of the largest and oldest Chicano/a student organizations in the country.

The CSUN branch has held fundraisers to help Arizona citizens pay for lawyers and fees in their court cases dealing with SB 1070 and HB 2281, but as a Chicana, Castaneda is still concerned for the future of the programs.

“The MAS program (Mexican-American studies) is one the most successful and biggest programs in Arizona, so if they knock out the main layer, it would be very simple to knock out Asian-American studies, Pan-African studies, Jewish studies and any programs minorities are a part of,” Castaneda warned. “For people to ban this is like they are banning your identity.”

Not just for Arizona

Beyond theoretically banning minorities’ identities as Castaneda mentioned, Biggers believes these types of laws have potential to affect everyone, not only minority groups in Arizona.

“Racial profiling dehumanizes all of us, regardless of your ethnicity, and we all need to confront the civil rights violations of such laws in Arizona and in any place,” Biggers said.