After years — on and off a total of 13 — I finally did it. I graduated with a bachelor’s degree from a university. The first in my family to do so, although my brother technically beat me to it graduating early from DeVry earlier in the year.

It was a great accomplishment, in spite of many setbacks. Some were self-created like fear, lack of self-esteem and confidence. Others were more circumstantial. Coming from a family that didn’t attend college, I did not receive the help and guidance in applying for admission, financial aid and other necessary steps. Oh, and I paid all of my first couple of years of community college working night shifts at FedEx because of this, all because I didn’t know I qualified for financial assistance.

Fast forward years later, after several strange jobs and life-or-death experiences, I finally graduated from college. My parents were proud. My little brothers looked up to me as a role model, someone that broke the mold and conquered his circumstances to make it out of the barrios of Van Nuys. My story would fuel their drive to get into college and succeed. And if they’d get apprehensive, I’d be there, a living example that it’s possible.

It was a wonderful feeling. But it didn’t happen.

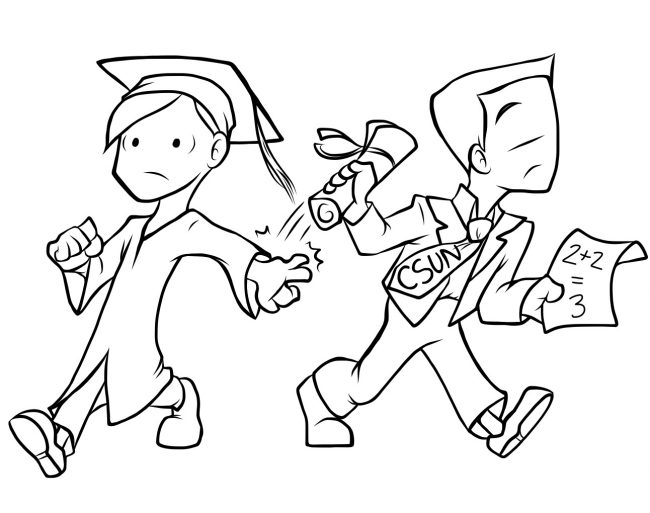

After completing the fall 2013 semester and being promoted from an intern to a staff member at a non-profit with a decent salary, I received an ominous letter in the mail from CSUN. It read, more or less:

“We regret to inform you that you have not earned your bachelor’s degree. Please call the graduation office as soon as you can to set up an appointment.”

I assumed it was a terrible mistake at first so I wasn’t really bothered. This happens all the time, I thought. Probably has to do with my exit-interview for that one loan I took out.

But when I emailed and asked why I got the letter, they insisted that I come in person. It was then that I knew it was serious. I emailed back asking what had happened. Got no specific response, just that I would have to wait to speak with someone.

I explained my new work schedule and my location (I live in downtown and work at USC). They finally budged and agreed to speak with me over the phone the following week. The graduation advisor said that I still had six units left to complete.

This was after I had completed 14 units in the fall semester, going over what was needed. What my advisor had recommended, just to be safe.

And now I needed six more?

She said my advisor miscounted my units that transferred from community college, and that if I wanted to graduate this May, I would have to enroll in six units before the deadline to register for classes. I asked when that was. Tomorrow, she said.

Instead of calling me with a specific plan or problem, CSUN decided on sending out mass letters to students that were wrongly told that they would graduate.

I immediately left work and drove over to CSUN. I wanted to meet with my adviser, journalism professor Taehyun Kim and the chair of the department, Linda Bowen.

After showing up unannounced at the journalism office, to the annoyance of its staff, I was able to sit down with Bowen. She proceeded to tell me that it was a matter of my many units collected at various communities colleges, and how through complicated counting, my entire time at CSUN was based off of a miscounting of completed and transferrable units.

Let me repeat myself: my entire time at CSUN was based off of a miscounting of completed and transferrable units.

But Bowen, head of the journalism faculty, told me that I should have kept better track of my units. A convenient argument, but impossible since my units were based on what the initial assessment was when I transferred from Los Angeles City College in the Fall 2012 semester.

She offered no apology. Even professor Kim apologized, which I immediately accepted. His classes have been one of the only places where I was taught radical mass communication theory and the various roles and purposes of journalism as a discipline and industry. But with Bowen, in spite of the institution’s miscounting and mismanagement of my transcripts, there was no ounce of repentance or empathy.

When I approached Kim with the news, he was more than sympathetic, re-counting my units and apologizing for the mistake—which, in his defense, was the fault of those that miscounted my units from Los Angeles City College and Los Angeles Valley College.

I had only one day left to register for classes for the Spring 2014 semester. I frantically called all the open classes and was rejected by all courses—even though there was available seating. The only classes that allowed me to register were Chicana/o studies, a few journalism courses and Pan-African studies.

And I am not the only one.

Mona Adem, another journalism student, had a similar problem at CSUN last fall. All for one unit.

According to Adem, toward the end of her stay at CSUN and because she was an international student, Bowen had to sign off on a document saying that she only had nine units left. This, in turn, was what eventually saved Adem the headache of having to move back to California and re-enroll at CSUN.

“Bowen had to sign a paper saying I only had nine units left,” she said. “I told them that Bowen had signed off on that paper. I held them to that.”

After a phone call with Bowen, Adem’s problems were over. But she was unsure what exactly happened.

“I don’t know what they did,” Adem said. “I only said that you had to fix this problem. So whatever they did, because I had that against them, it was hard for them to deny me. If I didn’t have [the signed document], I probably would have had to come back and take classes at CSUN. That’s my assumption anyway.”

There have been several stories of students receiving that ominous letter that alerted them to falsely declaring that they earned their bachelor’s degrees.

Megan Diskin, who double-majored in religious studies and journalism, also received that chilling letter.

“What freaked me out was that they didn’t mention it (in detail) in the letter,” she said.

When Diskin finally met with someone from the graduation office, they had said she was short by six units, but that she could possibly petition for three of those units from the religious studies department.

Diskin planned on meeting with someone from religious studies the very next day, but in double-checking the CSUN website for double-major criteria that same night, she realized that she, in fact, did meet all the requirements. The advisor was looking at religious studies not as the secondary major but as its own independent major. If you are double-majoring, the units required are less if it were the main major.

“How could these things fall through the cracks?” Diskin said. “Were they not paying attention that day? Do your job, that’s all I’m asking … there was no accountability. I don’t think they understand. You’ve been working so hard for this. There was no compassion. I started getting emotional in [the graduate advisor’s] office. I didn’t know what the problem was with my degree.”

Diskin has a lot of questions, probably more than I do.

“Why weren’t our unit problems addressed when we had our grad check papers signed?” Diskin asked. “The administration dropped the ball on that one.”

Where is the accountability in a state institution when one of the college’s chairs has the arrogance to tell a first-generation student, unfamiliar with the graduation process, that he or she should have kept better track? Where is the compassion, responsibility and accountability?

Due to the last-minute explanation of the miscounting of my units, I was unable to apply for financial aid and subsequently get my tuition covered. But fortunately I had the privilege of working for a boss who had a credit card to use to pay for my tuition to cover it until my financial aid went through.

The overall lesson here is on accountability and compassion, which CSUN has a deficit.

So consider this a blessing in disguise; you, CSUN, should take this as criticism to build your institution as a better model, a safe space for all students, but especially first-generation college graduates. Have compassion, own up to your mistakes (as we, including myself as a student, must also), don’t be afraid to be accountable and wrong.

CSUN, especially the journalism department, must ditch its arrogance and replace it with humbleness and compassion.