At one point in my life catcalls (when men yell or make a noise of a sexual nature at women to get their attention) were annoying, harmless and sometimes funny. That was before I learned that one of my female cousins had been raped at the age of 16.

It was a horribly touchy subject within my family and we hardly ever talked about it. My parents were already very protective of me. They enforced an early curfew and constantly checked in on me, but it was shortly after my cousin was raped that my mom sat me down and explicitly warned me.

“If you let them, men will take advantage of you,” she said.

I grew up in the city of Lynwood, near Compton in South Los Angeles. That was enough reason for my parents to give me a bottle of mace to keep with me at all times. Whenever I would leave home, my mom would take it from my purse and slip it into my pocket.

“It’ll be faster to pull out if you need it,” she said.

I felt like I was stepping onto a battlefield.

My cousin’s experience transformed those once harmless catcalls into threats and scared me into never wanting to walk anywhere alone. It was normal to see me walking down the street clutching my purse with my other hand in my pocket wrapped around that black cylinder of mace while constantly glancing over my shoulder.

My life as a young woman had been pushed to the edge and all the fear of rape had me wondering if I would truly be able to defend myself when the time came.

It was during my first year at CSUN that I had to commute a few times a week, which really worried my family. It was a three-hour trip each way, but my parents saw it as six hours that I would spend on a bus with dangerous, strange men.

It was later in college that I began to take gender and women’s studies classes and these interested me so much that I decided to make it my minor. It was in one of these classes that the topic of violence against women was frequently discussed. These discussions struck close to home because of all the experiences my family has had and made it almost difficult to participate.

We discussed many rape cases and what we realized was that women were not only victim to the crime itself but to the criminal system as well. They would be forced to recount their experience to countless individuals, only to be questioned over and over again, and possibly not believed.

She would become faceless, only a body of evidence being re-traumatized for the benefit of others. It seemed like no matter what the circumstances, the woman was always at fault for her own rape because of the steps she could have taken to prevent it.

This includes the usual: not walking alone at night, not drinking at a bar with strange men, learning some form of self-defense, being more selective when it comes to your outfit and being as loud as you can in the event of an attack. The only thing these tips do is put more blame on the victim than the attacker.

Recently, writer and political analyst Zerlina Maxwell appeared on the Sean Hannity show on FOX News. The main argument of this segment was that all women should have the right to own a gun in order to defend themselves against rape.

It was here that Maxwell explained that putting the responsibility of owning a gun on the woman just adds more blame to the victim. She explained that she had been raped by someone she knew and did not want to be told that having a gun may have prevented it.

Maxwell has written, “…many of us would rather advise women on the precautions they should take to avoid being raped as opposed to starting at the root of the problem: teaching men and boys not to be rapists in the first place.”

Her idea has become almost revolutionary. She stresses that women are not responsible for their own rapes and that they should not feel the need to constantly protect themselves. If anything, she believes that it is society that has failed to make prevention a priority.

Although men might feel the need to defend themselves and say that they don’t need to take any violence prevention courses, it’s important for them to connect with the experiences of women who have been raped.

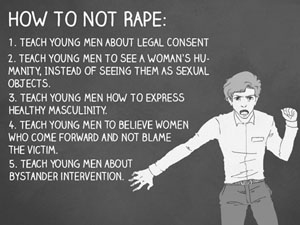

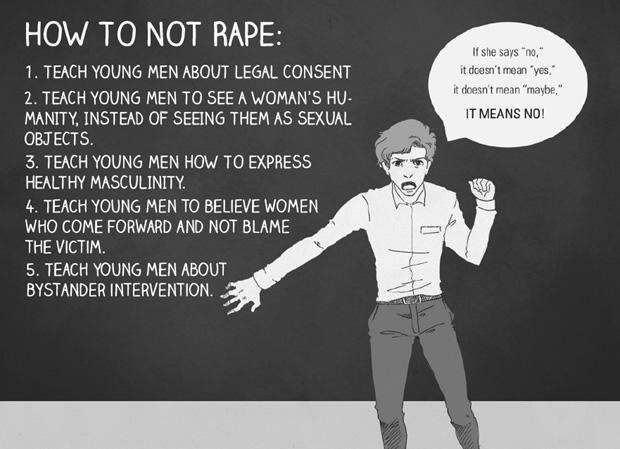

Maxwell outlined five ways to teach men not to rape:

1. Teach young men about legal consent.

2. Teach young men to see a woman’s humanity, instead of seeing them as sexual objects.

3. Teach young men how to express healthy masculinity.

4. Teach young men to believe women who come forward and not to blame the victim.

5. Teach young men about bystander intervention.

When it comes to a man’s masculinity, Maxwell believes that it should be expressed in a healthy manner. I believe a healthy masculinity includes ignoring all the stereotypes of what a man should be. This includes being stubborn, aggressive, overly confident, rebellious and even promiscuous.

It may be through these steps that prevention can begin in order to save women from such a traumatic experience and to stop blaming them for being raped. Although I still do take steps to protect myself, I now believe preventative measures should not just be taken by women but by men as well.

I used to blame my cousin for getting raped because she didn’t take the necessary precautions, but now I see how blameless she really was. There is an obvious need to educate men on a woman’s humanity instead of giving women tips on how to prevent rape. One can only hope that once this effort has been made, women will not only no longer be victims of this violent crime, but the criminal system as well.