With CSUN located in the heart of the San Fernando Valley and roughly 25 miles away from Los Angeles, the majority of its students are homegrown, in-state products.

In fact, 97 percent of the CSUN students are in-state students, according to College Board.

However, when it comes to athletics, the school’s athletics programs have made a concerted effort not only to get student-athletes from out of state, but also outside of the country.

“I love having kids from California. I love having kids from the United States,” CSUN men’s soccer head coach Terry Davila said. “But whoever really loves our university and wants to come here, I’m willing to recruit them.”

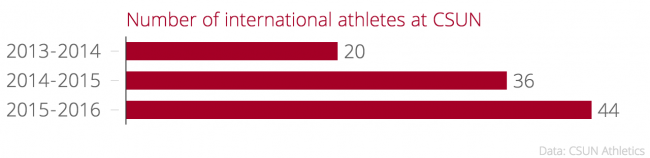

As of the beginning of the 2015-2016 athletics year, there are 44 foreign-born athletes scattered across the 17 athletic teams at CSUN.

Although that may seem like a drop in the bucket compared to the 17,653 that the National Collegiate Athletic Association reported in 2009-2010, those 44 athletes have paid dividends for the CSUN.

The payoff isn’t more evident than on the men’s soccer team, which features a school-high eight foreign-born student-athletes.

However, the reward for having several talented foreign prospects doesn’t come without any setbacks or difficulties, mainly the language barrier.

“The English language, often times English is their second language,” Davila said. “They have to get adapted and assimilated to the English language and learn how to study in English.”

In spite of the language and cultural barriers that are bound to arise, the university’s coaches have made a conscious effort to reassure potential student-athletes that they do have a strong foundation in place for them to get used to the environment.

“I talked to all of the coaches during the recruiting process and they were all very, very, helpful,” said Tessa Boagni, a sophomore center from Christchurch, New Zealand on the women’s basketball team. “And they told me what they’d do and how they would help me.”

With that said, the growing amount of international student-athletes on certain teams has also made it more accessible for coaches to add and reach out to that demographic of players.

Granted, having a few international students does open up the door – or floodgates, in some instances. For more, there are still a few hurdles to jump over when recruiting international players that aren’t there when recruiting national players.

A common practice in international recruiting is for recruits to make highlight films and email them out to programs and universities they are interested in playing and attending.

Even though that does give coaches back in the United States a chance to see what a player can do physically, they are at a disadvantage because of the small sample size given.

“It is a disadvantage because if you don’t get to see the kid actually play in a competition, [for] some kids, their emotions can get the best of them in situations,” Bracken said. “Those are what you like to see.”

The clips, although a useful way to showcase skills and talent, do not tell the full story, too.

“You can always manage clips — like you missed 50 chances before you score the goal and you put the goal in the clip,” said Pol Schonofer Bartra, a junior defender on the CSUN men’s soccer team and a native of Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.“You don’t put the other 20 missed shots.”

The rely on a concise highlight reel isn’t only frustrating for coaches, but also the players who send them out.

“Obviously the coaches can go and watch someone from Pasadena like five times. They can go watch a live basketball game and see them play and talk to them,” Boagni said. “Internationally, you can only rely on the video footage, talking to them on Skype and waiting for the time zones to connect to talk to them. I guess that whole aspect is harder with recruiting.”

Even after getting themselves on the radar of coaches and programs, international players and universities must go through a more extensive and uncertain process with the NCAA when it comes from an educational standpoint.

“It’s a little headache because you are always concerned that because our grading systems are so different that maybe in New Zealand is good, might not be as good here,” Boagni said.

In CSUN’s case though, the school works closely with the NCAA every step of the way, to make sure that the athlete is eligible academically.

“All the coaches really helped out with that, we just sent over the paperwork, and they went over with the NCAA and they sorted it out,” Boagni said. “It’s not really a headache for you unless you’ve done really bad.”

Some special cases, like in soccer, where student-athletes come from countries where it is more common to turn professional earlier in their lives, schools must also work with the NCAA in making sure their amateur status is still in tact.

“The translation of the grades, there’s a lot of stuff,” Davila said. “They [the NCAA] got to make sure they haven’t played pro in their country and have never been paid before.”

Nevertheless, both players and coaches believe that any difficulties recruiting pay off in the form of high-level competition and the opportunity to get an education.

“Coming here, I can get a degree, a very good degree,” said Bartra. “And I can play at a good level of D1 [Division I].”