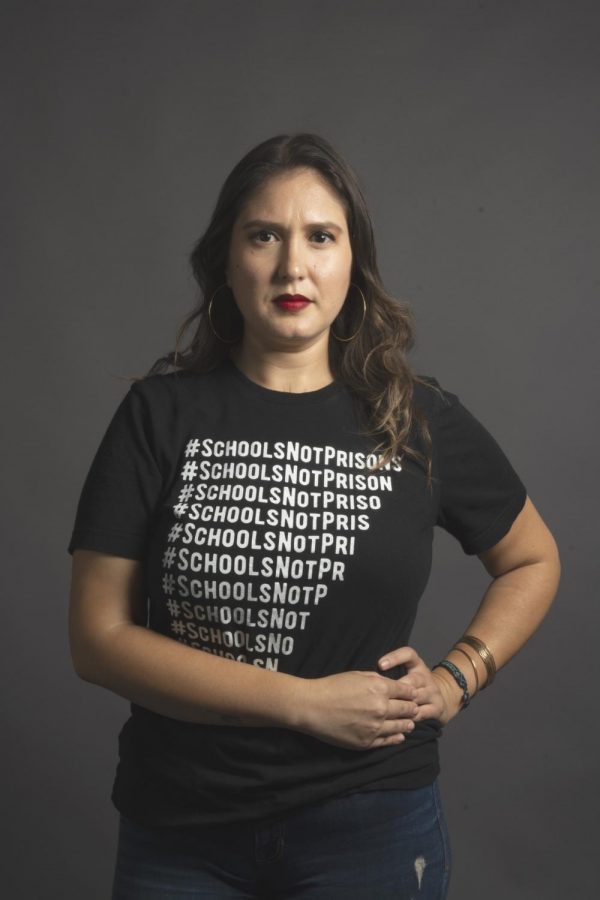

Lily Gonzalez was restarting her life at CSUN when one day she read an article about Danny Murillo, a formerly incarcerated student at UC Berkeley, who founded the Underground Scholars Initiative. After reading the article, she thought, “Wow, people like me do go to school.”

As a formerly incarcerated student herself, Gonzalez reached out to him, asking how she could bring something like USI to CSUN. Murillo connected her with Johnny Czifra, whose brother Steven was Murillo’s co-founder of USI. Gonzalez and Czifra would meet every Thursday after class in the Chicano House on campus; they had no idea what they were doing at first, but they knew why they were doing it.

“We just knew from our own lived experience that there was a huge fissure at CSUN and people like her and me were falling through it,” Czifra said. As a formerly incarcerated person, he recognized the potential for improvement that higher education would lead him to.

Gonzalez worked for Homeboy Industries after she was released. She was working at Homegirl Café, cutting chilis, when she got notified of her acceptance letter from CSUN.

“Fuck these chilis, I’m going to school,” she said to herself. For her, education wasn’t in her plan, it was purely survival.

The formerly incarcerated have trouble finding a way back to school, a support system or a job because of their background. They face barriers while enrolling in college such as discriminatory admissions practices, financial aid restrictions and even occupational license negations, according to a report released by the Prison Policy Initiative. Their chances of finding employment is slim due to these barriers.

Los Angeles County has the largest jail system in the U.S. and holds the most inmates, and also happens to be one of the few jail systems that offers rehabilitation, vocational and educational programs, with 58% of inmates participating in these programs, according to the Los Angeles Almanac.

But Gonzalez and Czifra know that LA has a long way to go for providing more opportunities for the formerly incarcerated. That is why they first attempted to bring Project Rebound to CSUN.

Project Rebound is a program that provides formerly incarcerated students the resources and opportunities they need for transitioning to college. It was originally established in 1967 at San Francisco State University.

Gonzalez explained that in 2015, SFSU offered grants to extend Project Rebound to all 23 CSUs, but by 2016 it only reached nine campuses.

“CSUN was one of those that said, ‘Nah we’re out,’ and their response was lack of infrastructure,” said Gonzalez. To this day she still does not know what that meant.

Gonzalez and Czifra, meanwhile, created Revolutionary Scholars. From CSUN they built access to resources such as Homeboy Industries and other correctional facilities. They became involved in the community to help those impacted by criminalization, but their main efforts have been to get Project Rebound established at CSUN in order to provide academic and peer counseling, mentorship and help with financial matters.

Earlier this year Gonzalez fought for an extended budget for Project Rebound with Governor Gavin Newsom’s new budget proposal from January. The budget was approved for $3.3 million to expand Project Rebound to all CSUs on June 27, including additional funding for other areas in the CSU/UC system. However, for CSUN to establish Project Rebound, Revolutionary Scholars needs a letter from the administration to bring the formerly incarcerated the support they need.

“We need actual tangible support,” said Gonzalez.

She has been working with William Watkins, CSUN Vice President for Student Affairs, in getting the letter through administration. Watkins commented that faculty and students are working on positioning CSUN within Project Rebound. Several students have worked with Project Rebound and they have been quite helpful as they clarify the information necessary to submit a request for funding, he said.

“I understand that a letter of support from university administration will need to be a part of the university’s request and I fully anticipate that such a letter will be provided,” said Watkins.

Czifra acknowledges that Revolutionary Scholars is a grassroots organization compared to Project Rebound, and social justice for the formerly incarcerated is picking up steam. However, money seems to be the number one hurdle in moving full steam ahead.

“Money is tricky and the approach to spending it has to be responsible, I get that. I also understand that a practice in patience may serve RS well,” said Czifra. “That being said, this is 2019, going on five years of work on this project for Lily and myself. Things could move a little more quickly.”

When Gonzalez was at CSUN she applied for a position on campus but was denied because of her background. She later worked on a hiring initiative to be passed in LA County where restrictions on employment based on criminal records were lessened, according to the LA Times. UC Berkeley is one of the many institutions that have banned the box option to check for criminal records from employment applications, Gonzalez said.

Czifra pointed out that seeking assistance can be difficult for those impacted by incarceration, but both Gonzalez and Czifra know that speaking up about their identities has helped other students persevere through their challenges.

“We know what it is to walk in those shoes, so we show that it can be done. We also let them know that the same way we do for them, they can do for the next person,” said Czifra.

Gonzalez stated that people like herself are out there writing the policies because no one will hire them.

“How are they going to come home,” she said, “to a place where employment is not offered, and society treats them differently? If I came to CSUN and I didn’t do anything for the formerly incarcerated people after us, then I didn’t do shit.”

Gonzalez is a grad student at CSUN, with two daughters, the eldest off to SFSU for the fall. For her, getting her daughter to college has been her biggest accomplishment. She said that what CSUN needs is allies with its administrators to find solutions for people like her.

Though Revolutionary Scholars is new, Gonzalez pointed out that the stigma is still big at CSUN and that is why she feels people are not vocal of their past. That’s why it’s on Revolutionary Scholars to take charge in the march for social justice.

“We don’t cast them aside,” said Czifra. “We embrace them and help them, to help themselves, to help others.”