Recounting former CSUN President Harrison’s eight years in office

January 17, 2021

During her eight years as CSUN’s president, Dianne F. Harrison has encountered a variety of ups and downs, such as handling budget cuts, navigating through the COVID-19 pandemic and increasing the amount of philanthropy received by the university.

We broke down some of the key issues that happened during her presidency to see what she was able to accomplish and where this leaves her successor, Erika D. Beck.

Advancing student success

Harrison joined the university at a time where the CSU was facing budget cuts and other financial hardships. CSUN was deciding whether to raise tuition or enroll fewer students, where they decided to go with the latter.

“These are difficult times for everyone, and we must pick the best among bad choices,” Harrison told the Daily Sundial in 2012. “We must decide what our primary core values are — quality education and graduating are ours.”

Harrison was able to uphold these values as CSUN’s overall graduation rates have slowly increased since she took charge in 2012.

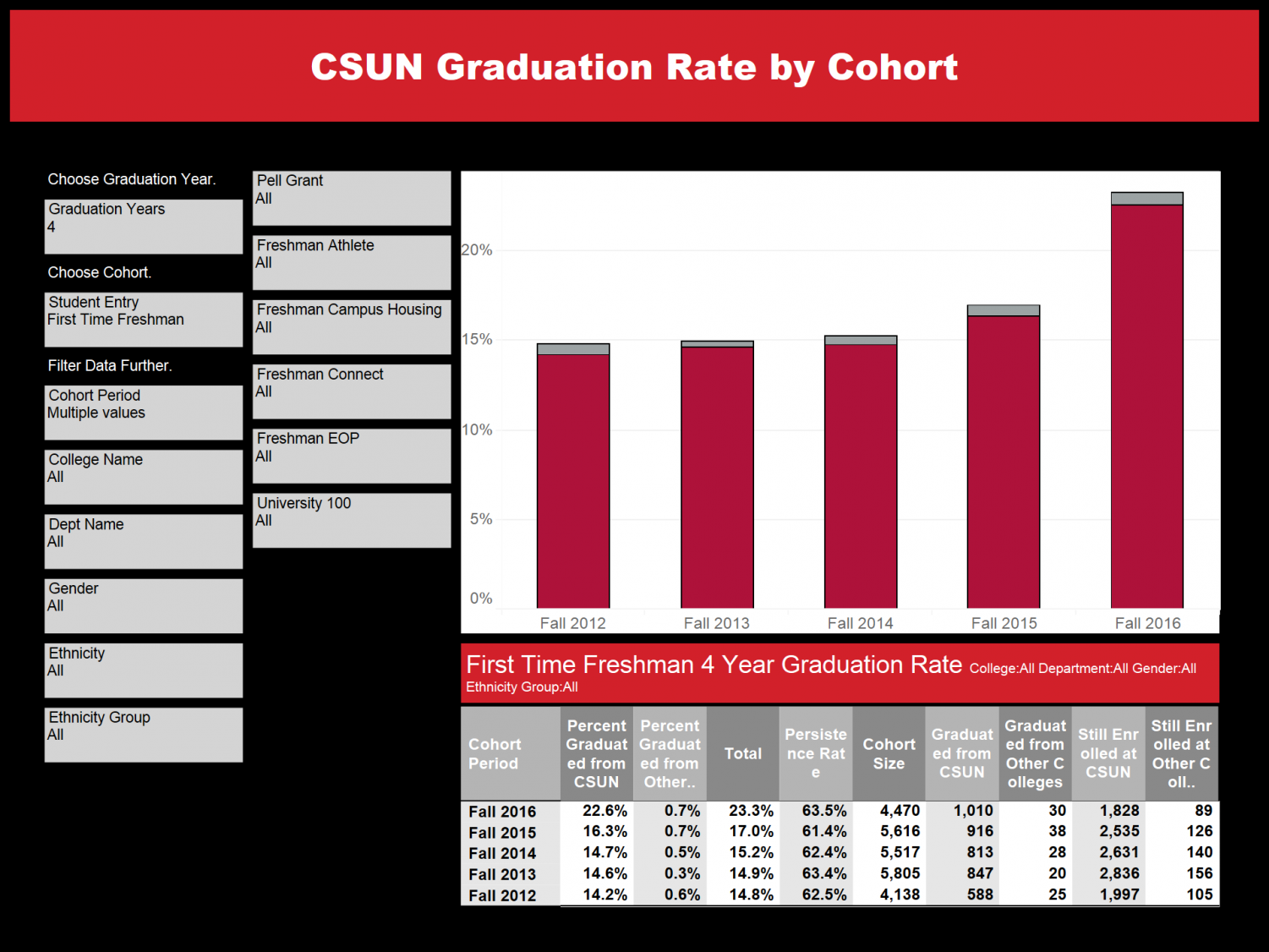

The first time freshman four-year graduation rate has increased since 2012, according to CSUN Counts. The graduation rate for the fall 2012 cohort was approximately 14%. The fall 2016 freshman cohort graduated at a rate of over 22%.

Among first-time transfer students, 73% of the fall 2012 cohort graduated from CSUN in four years. More than 77% of the 2016 first time transfer cohort graduated from CSUN in four years.

CSU system-wide programs created goals for each campus to fulfill. The Graduation Initiative 2025 was created in 2015 by then-Chancellor Timothy P. White in an effort to increase graduation rates and narrow equity gaps among CSU students.

That same year, Harrison launched Matador Momentum, which is a working group concerned with student success.

The working group was developed after CSUN submitted an application to be part of a first-year experience initiative led by the American Association of State Colleges and Universities. CSUN was one of 44 institutions selected as part of the initiative.

The AASC&U initiative ended in 2018, but Matador Momentum continued its work on campus. Since then, the group developed multiple student success campaigns with prizes for students, updated mentoring programs, awarded distinguished students and supported the Provost’s Student Success Series, according to its most recent progress report.

CSUN’s student success campaign, Matadors Rising, works in alignment with GI 2025 to help students graduate on time by encouraging students to enroll in more units.

However, CSUN faced a challenge as the plans to realign the General Education Breadth Requirements across all CSU campuses threatened a significant area of the CSUN community.

In 2017, White released Executive Order 1100, which required CSU campuses to standardize general education requirements for first-time freshmen and transfer students. Under the new requirements, students would need to complete a total of 48 units in subject areas A through E in order to graduate.

EO 1100 required CSUN to eliminate Section F to align with the new requirements in order to meet one of the Graduation Initiative 2025’s goals: increasing graduation rates.

Students and faculty responded with multiple protests against EO 1100 and its revised version, EO 1100-R. They recalled CSUN’s history of activism in the 1960s when students protested for the administration to hire faculty from underrepresented communities, support ethnic studies and more.

They criticized Harrison for not advocating enough to keep ethnic studies, such as sending feedback to the Chancellor’s Office on the educational importance of keeping Section F in the curriculum.

In an email sent to the campus community in 2017, Harrison shared there needed to be more conversation within the campus community to find a solution for going forward with the Chancellor’s Office’s plans on EO 1100. She wrote that she was proud of the students and faculty for their efforts to preserve ethnic studies, gender, women and cultural studies departments.

“I will never stop advocating for our students and our campus values. Second, we are proud of CSUN’s national leadership position in ethnic, gender, women’s and cultural studies, and we will continue to advance the important work being done in these departments and programs,” Harrison wrote.

Working relationship with faculty governance

After the Faculty Senate voted not to endorse the executive order, the Chancellor’s Office released EO 1100-R, which allowed CSUN to keep Section F. The revision ensured this by stating that students are required to take three units in upper division general education courses in sections B, C and D.

Yet, the Faculty Senate voted to not participate in the implementation of EO 1100-R.

Harrison later established the General Education Task Force to make recommendations with the order. The task force provided suggestions, but they did not align with the executive order and left few options. In August 2018, the Chancellor’s Office sent a memo to Harrison stating that CSUN had until fall 2019 to “come into compliance with EO 1100-R.”

“This is not a decision that I take lightly. Shared governance is something I believe in deeply, and I make this decision only after many attempts at finding solutions,” Harrison wrote in a memo later that month. “But we have run out of time and must move forward to be in alignment with the CSU.”

One of the most notable protests took place during the New Student Convocation in September 2018. Students demanded clarity from Harrison, despite her statement that EO 1100-R would not jeopardize Section F.

The faculty also raised questions about EO 1100-R. In a memo from the Coalition Against EO 1100-R & EO 1110, faculty members stated that the impact on Section F as a result of the mandated three units was uncertain, and could potentially be detrimental to the courses under Section F.

In November 2018, an ad hoc Faculty Senate Committee wrote a resolution of no confidence in President Harrison. A vote of no confidence is one of the few tools a campus has to remedy a negative situation. The resolution wouldn’t have removed Harrison from her position but would send a strong message to the Board of Trustees and chancellor of the CSU, according to the resolution.

Professor Kathryn Sorrells from the Department of Communication led the committee, which collected information, data and documentation from meetings and discussions with faculty, staff and students.

After reviewing a year’s worth of material, the committee created a resolution that stated the Faculty Senate would like to “bring attention to and accountability for the pattern of failed leadership at CSUN” by Harrison, and to “restore transparency, accountability and democracy” on campus.

The Faculty Senate reviewed the resolution and debated the language of the document. Some statements were struck from the document and the group never agreed on a final resolution. On Dec. 7, 2018, the Faculty Senate failed to pass the resolution 32-26.

CSUN eventually implemented EO 1100-R at the start of the fall 2019 semester.

In response, the Faculty Senate voted no confidence in then-Chancellor White to lead the CSU, a resolution constructed by Sorrells and other ad hoc committee members.

“Our students and the students across the CSU system deserve a leader who, through the policies he implements, actually supports students’ success and where that’s a priority,” Sorrells told the Daily Sundial.

Adam Swenson, a philosophy professor, reflected back on how Harrison handled the challenges of the executive orders.

Recalling his time as Faculty Senate president from 2014 to 2018, Swenson described his working relationship with Harrison as productive and talked about Harrison’s transparency, inclusivity, and openness to hearing feedback.

“I always had the sense that she really wanted to know what was going on with faculty and what people were thinking,” Swenson said. “She was always curious and listened, and she’d always ask good questions to understand what was really going on.”

Current Faculty Senate President Michael Neubauer has been with CSUN for 26 years as a mathematics professor and has seen different leadership styles from three campus presidents.

Neubauer said the previous president, Joelene Koester, was known for having a strong campus presence. He said Koester was known for walking around campus on Friday afternoons and visiting people’s offices.

“There was clearly a different feel to the presidencies,” Neubauer said.

Neubauer said that based on his view of Harrison, he saw her putting a focus on external connections and networking to increase the university’s reputation. He said that Harrison has had tremendous success in fundraising and recognizes the benefits these donations have on the campus as a whole.

During the fall semester, Neubauer and Harrison met twice a month to discuss Faculty Senate matters. He said that while they may not agree on everything, the two maintained a productive working relationship.

“I think we both understand the role we are playing in this and we’re acting accordingly,” Neubauer said. “For the benefit of the institution.”

Pushing for diversity and inclusion

Long before Harrison attained her first role in administration at Florida State University, she was an assistant professor with a background in social work who taught a class on human sexuality. Her class discussed many topics, such as sexual assault and prevention — a space that Harrison dedicated herself to learn about for decades.

She said her passion for working on Title IX as an administrator came from those days as a professor.

In 2019, Harrison served as a panelist for the NCAA Convention Association-Wide Sexual Violence Prevention where she shared her expertise on the best practices of Title IX. There she met another panelist, Barret Morris, then-director of compliance and Title IX coordinator at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Later that day, she approached him and asked if he had ever heard of CSUN as she believed he could fill the recently vacant spot as the Title IX Coordinator. He said he admired her passion when she spoke on the subject, so he applied and was hired later that year.

Once he arrived, Harrison asked that Title IX training for athletes become his priority. Morris says that with the help of Harrison, they’ve helped put athletics “on the right track” with regard to sexual assault allegations against college athletes.

Prior to his arrival, there were “roughly six or more complaints of sexual assault investigated against [college] athletes,” said Morris in an email.

After Morris created customized training for the athletes, he said there were zero complaints or investigations among athletes later that year.

He said that the best thing about working with Harrison is her pursuit for equity and inclusion in the workspace, for students, faculty and staff.

“She sets a tone in the environment that supports inclusion and that is something that is important to me because sometimes presidents can be very isolated. Here the president cares and wants to know about specific things that happen around the campus,” Morris said.

In 2018, Harrison hired Natalie Mason-Kinsey as chief diversity officer to help measure the level of effectiveness of diversity and inclusion initiatives and to help with recruitment and retention rates of faculty across the campus.

“One of the hard things about having a diversity goal is that it’s an ever-moving target,” Mason-Kinsey said.

Mason-Kinsey serves on the Commission on Diversity and Inclusion Initiatives, a program established by Harrison. In August 2020, Harrison released a 10-point campus action plan on improving diversity and inclusion in response to the George Floyd protests and Black Lives Matter movement.

As part of the plan, the Commission announced the Diversity and Equity Innovation grants to support projects and creative work that educate the CSUN community on social justice issues and anti-racism. Mason-Kinsey said Harrison shows commitment to the initiatives despite recent budget cuts.

“Her putting the money there says something. We fund what we find important,” Mason-Kinsey said.

Harrison also made it clear that her job as a leader is to ensure the deans and hiring faculty to hire diverse faculty, as “ this is the right thing to do … the necessary thing to do.”

She, like the chief diversity officer, emphasized that it’s more than just recruiting diverse faculty — it’s also about retention rates and making sure that the diversity is not compartmentalized.

Harrison acknowledged that CSUN still has to work on its diversifying hires. While CSUN has a total of over 40% tenure-track faculty of color, a majority of those numbers come from ethnic studies departments, but few are seen in other departments such as engineering, business and economics, according to data from CSUN profiles and CSUN counts.

The Faculty Senate released a list of demands for the administration over the summer, addressing the same concerns and demanding that the university “[s]et targets and provide updates on the progress of hiring tenure-track faculty of color; set the expectation that faculty hired by a college in an academic year will increase diversity in the college.”

The demands were in response to the George Floyd summer protests along with other measures to address concerns raised by students.

In June, the Northridge Black Lives Matter chapter, a group formed by CSUN students, led a protest in Northridge and demanded the removal of the CSUN campus police and the CSUN jail.

Harrison said that while she listened to the demands, she said removing campus police is “not going to happen.” If the CSUN Police Department was removed, the Los Angeles Police Department would step in and deal with any campus crimes or threats, citing the mass shooting threats during the December 2018 finals week as an example.

When the mass shooter threats were found on a men’s bathroom stall and in an anonymous letter, the information spread quickly over social media before reaching the police department. Harrison said the administration received lots of criticism for the delayed response.

“All I heard [from critics] was you have to keep the campus safe ... you do that by having our [campus] police department,” said Harrison.

She says the LAPD does not share the same philosophy as the CSUN P.D.

“All chief of police of the Cal State system met and adopted 21st century policing that came out under Obama, adopting among themselves significant changes that would take place in the police department,” Harrison said. “One of the changes was if you have police, you should have a police advisory group. If there was ever any question or complaint about the police, the complaints would go to the group.”

The group is currently in the process of formation and consists of students, faculty members and community members.

Later in 2019, students expressed their dismay toward the library being named after former CSUN president Delmar T. Oviatt. The Students of Color Coalition and other student activists claimed Oviatt was racist as he was an “opponent to the creation and existence of cultural studies” in a letter to the editor.

The activist group supported their claims of Oviatt’s racism by citing how Oviatt’s declaration of a state of emergency on campus in 1969 allowed police to put down demonstrations led by Black students and students of color. Oviatt’s declaration resulted in the arrest of 275 demonstrators and injury to one protester’s eye, according to the Daily Sundial’s reporting.

Harrison created a working group to evaluate the claims through extensive research. The group suggested that the library’s name be changed and the proposal was approved by the Faculty Senate and Associated Students.

On Dec. 18, 2020, Harrison announced that the library would be renamed University Library, following the approval of then-Chancellor White.

“Given the importance of diversity and inclusion to CSUN today, and in order to make the campus as welcoming and inclusive as possible, the President’s Cabinet supported the working group’s recommendation to retire the Oviatt name from our iconic library and neighboring lawn,” Harrison said.

Bringing in funding for the university

CSUN’s general operating budget comes from two primary sources: student fees and state funding. Ii In 2011, the year prior to the start of Harrison’s presidency, CSUN faced large budget cuts as the CSU system’s budget was slashed to $560 million by the state. The loss of funding resulted in fewer classes being offered and some students not being able to enroll in the mandatory course to graduate.

“The bottom line is that CSUN has more students than it is funded to serve. Specifically, CSUN is currently serving approximately 7% more students than the enrollment target assigned to this campus,” a 2012 statement reads.

This was later resolved the year after through increased funding from the state.

While the state’s funding has fluctuated throughout Harrison’s tenure at CSUN, state funds generally account for 50% of the university’s budget.

When the state cuts funding, it leaves the CSU system in a tough financial decision as they are usually forced to raise student fees.

CSUN tries to play a tough balancing act between its use of state allocation and student fees to fund its general operation.

Colin Donahue, CSUN’s vice president of administration and finance, explained that although the university relies on state funding, CSUN is constantly looking for donations and other sources of outside funding to help improve the student experience.

Although philanthropic donations do not fund the university’s day-to-day operations such as payroll and other fees, the donations go to scholarships, funds for building maintenance and other funds. In turn, the donations free up the general fund budget for the university’s operations.

Harrison and her team were able to accomplish this with philanthropic donations, licensing and other streams of revenue.

For example, between 2007 and 2012, CSUN received an average of $14 million per year in contributions, grants, program service revenue and investment income according to tax documents. In Harrison’s eight years as president, the average contributions were $24 million a year — a 73% increase.

CSUN also set a record for philanthropic donations during Harrison’s leadership. During the 2017-2018 school year, the university received $31.7 million in total donations, the most amount received in university history, according to CSUN Today.

Harrison also used the Valley Performing Arts Center to boost CSUN’s reputation in 2017. The Younes & Soraya Nazarian Family Foundation donated $17 million to the performing arts center. The family explained this gift to CSUN was a product of the arts that helped them in their lives.

“CSUN’s commitment to making the arts accessible, its inclusive approach to artistic programming, the university’s deep diversity and its vital place in the community all contributed to our family’s decision to make this investment,” Soraya Sarah Nazarian told CSUN Today in 2017.

The performing center’s name was changed to the Younes and Soraya Nazarian Center for the Performing Arts in recognition of the family’s donation.

Furthermore, CSUN has had more individual donors during Harrison’s time than in university history. From 2014 to 2018, the university had over 15,000 individual donors, compared to the less than 8,000 individual donors from the years prior, according to CSUN Today.

Donahue, who has been working at CSUN since 1996, attributed the rise in donations to Harrison as she provided resources for the university to seek these donations. “It’s been a focal point for her and she has helped CSUN make a mark in the L.A. region and nationally, bringing in more donations,” Donahue said.

Using research and sustainability programs to benefit campus, community

Another way of building CSUN’s recognition is through research and sponsored programs.

Over the last seven years, the Research and Sponsored Program office has introduced hundreds of research and creative programs and received millions in grant funding.

Over the last five years, CSUN has brought in an average of around $30 million in grants yearly. These grants — mostly federal — fund research programs on campus from nutrition to biomedical research. One such program is BUILD PODER, which has received $41 million since it first launched in 2014.

BUILD PODER, a research program that includes faculty and undergraduate student researchers, focuses on improving diversity from underrepresented groups in the STEM field.

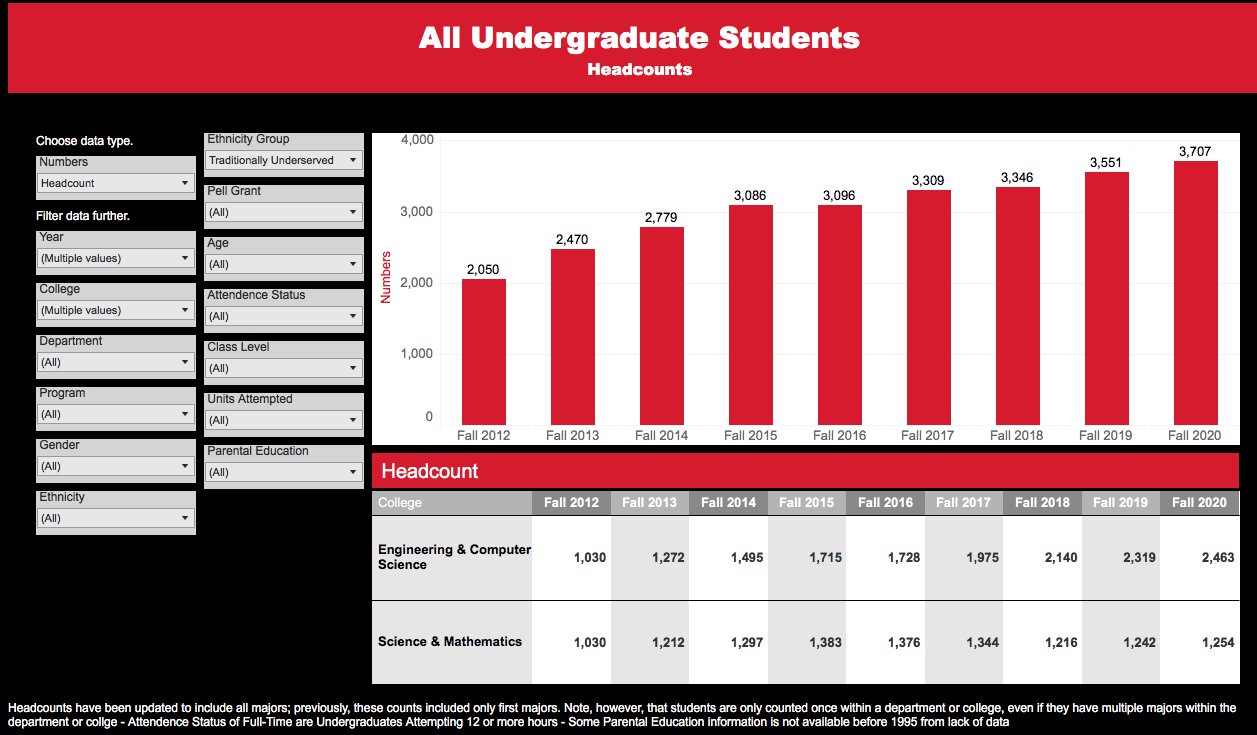

The efforts seem to pay off, with a steady increase in undergraduate enrollment since the launch in 2014.

Laura Serrano, the central grants officer for the RSP office explains the importance of programs like BUILD PODER at an institution like CSUN, where over half of the undergraduate student population is Latinx.

“We can create the graduates of scientists that can come out and make our science more reflective of who we are as a nation,” said Serrano.

Other research themes CSUN professors are involved in include low-income food insecurity and climate change.

Annette A. Besnilian, executive director of the Marilyn Magaram Center for Food Science, was awarded a $121,000 grant from the L.A. County Department of Public Health, bringing the total project award to about $317,000, during summer 2020 to research the CalFresh Healthy Living Program. The program focuses on nutrition education and physical activity to SNAP-Ed eligible applicants.

Research shows that low-income Latinx adults and children are at risk for diabetes and obesity. Besnilian said her research will follow the behavioral outcomes that may improve the consumption of healthy foods amongst low-income communities.

While some are doing research, others use research to make change happen on the ground level. At a campus such as CSUN, where the campus facilitates over 30,000 students a semester, waste can pile up quickly.

Austin Eriksson, CSUN’s director of energy and sustainability said that part of Harrison’s lasting impact was building on the original mission of the climate commitment and laying the groundwork for a myriad of green solutions at CSUN, such as landscaping and energy conservation.

“Without her leadership, I don’t think we would have a climate commitment, and made as much progress towards our sustainability and climate goals without her championing it and being a voice,” Eriksson said.

Sustainability at CSUN is nationally recognized, ranking fifth in the Sustainable Campus Index in 2019, which ranks sustainability in different categories at universities across the nation.

“CSUN is a leader in the CSU and nationally due in large part to President Harrison’s passion for and support of sustainability,” said Sarah Johnson, sustainability program analyst administrative coordinator for CSUN’s the Institute of Sustainability.

However, Johnson said CSUN still faces some challenges.

“We have set ambitious goals to divert 95% of all campus waste from landfills by 2025 and have zero net emissions by 2040,” Johnson said.

Johnson also said CSUN needed to better integrate sustainability into the course curriculum, which she hopes Harrison’s successor will take on.

“The institute has worked hard to build strong partnerships with the campus and broader community, but these can definitely be expanded because sustainability is integral to, not separate from, any discipline or program,” Johnson said.

Handling the COVID-19 pandemic

Days after Gov. Gavin Newsom announced the statewide “Stay at Home” orders in March 2020, Harrison released a statement postponing her retirement to continue leading the university during the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The campus closed to limited in-person classes after the 2020 spring break and the university took the COVID-19 measures one day at a time. In April, she announced a CSUN employee tested positive for COVID-19. As of Jan. 11, there have been 143 confirmed cases of COVID-19 from the campus community, although this number only reflects those who have reported the cases to the campus.

Once Harrison announced the fall 2020 semester would be mostly online — with some in-person classes — some students called on the university to refund student fees for services they did not have access to, such as the gym and library.

Harrison explained that the fees would remain the same.

“If we provide students with full academic credit for the courses that they take, regardless of the means in which they’re delivered … no portion of that tuition or mandatory fees will be reduced,” Harrison said to the Daily Sundial in May 2020.

The state of the pandemic has been a rollercoaster for everyone, and Harrison and her team were no exception.

“It’s probably one of the most difficult times that I have experienced as a campus president and the most difficult challenge,” Harrison said.

She, like the rest of the CSUN community, experienced the neverending “Zoom fatigue” and was apart from her family for safety precautions. She watched her grandchild take his first steps on Facetime, and said the hardest part was that she could not hug him.

Turning off her switch won’t be easy as she retires, a word she doesn’t even like to use after working for 44 years in academia. She doesn’t know what she’ll do next, but for now, she can move her elliptical to reggae music and The Beatles for as long as she wants.

Editor’s note: Story updated on Jan. 18 at 2:19 p.m.