As the temperatures drop in Southern California, I walk the frigid boulevard and find my thoughts rising and entwining with my frosty breath. The moon slung low and my hands wedged firmly in my pocket clasping my phone. Dreading the sporadically scheduled phone call to my aging father. The calls are few and far between but the filial guilt is ever pervading and relentless and daily. Especially so during the holiday season. It’s the curse of having Vietnamese immigrant parents. And the price paid for absconding the watchful and cosseting gaze of home at the earliest age of opportunity.

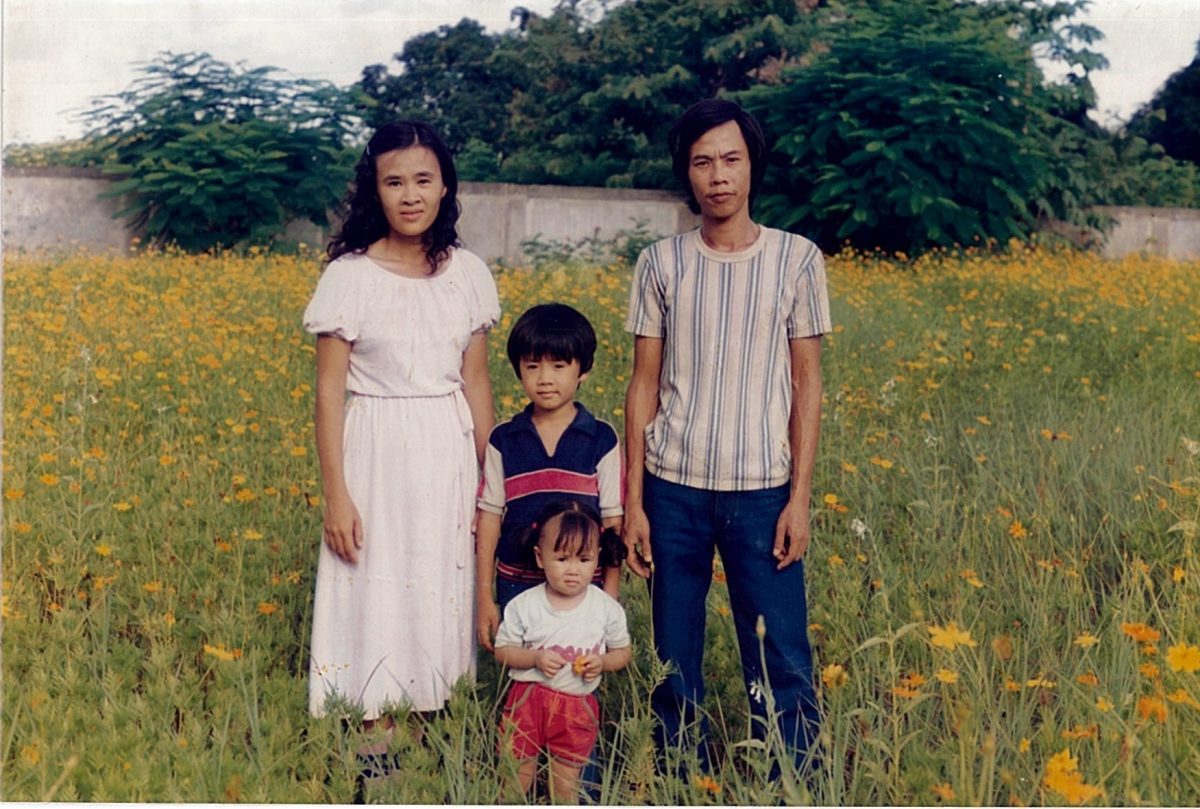

My father arrived as a refugee from Vietnam in his mid-twenties with two children in tow and had a third by the time he was my current age. Did he have wistful nights like this? Pondering the moon as he trudged back and forth to any number of low-wage jobs to cobble together a living for the family dependent upon his sweat, tears, and unceasing toil? I crack the collar of my jacket a little snugger. And my mind occupies itself with youthful memories of gallivanting in my parent’s closet. That specific olfactory confluence of dust and mothballs. Memories of being six or seven and completely swimming in my father’s overcoat. The armholes a gaping maw in which my nourished yet puny arms would orbit within.

Vietnam is a tropical country. And low-Celsius Los Angeles winters were a climate shock to my father that precipitated the acquisition of a sturdy coat during the 80s. Secondhand and absurdly unfashionable. It was imitation leather with splotches of brown bygone stains accumulated yester-decade. Though it didn’t look like much, akin to my father’s meager frame, it commanded an indomitable utility and sense of function. It was this pragmatic accoutrement that I associate most with my father.

That unsinkable garment laced with cigarette smoke and residual oil from his blue-collar machinist job. The temperature seems to dip another centigrade and horripilations hoard upon my arms. Like his own hardy pleather pelt, throughout the years, my father would drape several layers of similar protection over my shoulders. A coat of cultural armor from having to assimilate to this new country without losing our sense of Vietnamese roots and identity. A gutsy garb to swaddle us from the complacency of middling grades instilling within us a resolve to work harder and longer to compete for that dwindling slice of American dream. And most importantly, that amazing technoculture dreamcoat of consolation as he worked his hands to surly calluses so that his children were afforded better opportunities. And, contrary to my father’s employment history, the tunic of comfort that I shouldn’t feel resentment for my degreed and largely white-collar sensibilities.

It’s that last coat that I currently find myself cloaked in. My father retired a few years ago during the pandemic and hung up his overburdened coat-husk on the peg of pensions and savings and attempts at finally enjoying the few remaining twilight years left. Unfortunately, my father finds himself lumped into the category for whom retirement does not suit. Far be it from the romantic images of fly-fishing, gardening, and sending postcards from far-flung locales. Alas, he finds himself alone and drinking a majority of the day. According to the National Institute of Health, more than sixteen percent of men consumed at least 28 units of alcohol per week upon retirement. That statistic would be a modest one at the rate I’ve witnessed my father on a leisurely bender.

It’s cultural. Ingrained into his very marrow. Before he met my mother and began the familial journey, binge drinking was part and parcel with everyday Vietnamese social life. According to the World Health Organization, seventy-seven percent of Vietnamese men are heavy drinkers. Though slight in physical frame, my father could make short work of a case of Rémy Martin while retaining a raconteur’s wit captivating the party with an anecdote delivered with surgical precision. Today, my father tells stories to ghosts in his periphery as he laments the phone that long ago stopped ringing.

The clock recedes further toward midnight. An hour that otherwise would be untoward to make a phone call home. An hour that unfortunately I know my father to be wide awake and wading toward the bottom of a bottle still. His arms spindly and atrophied from a lack of physical activity and trembling within his sleeves despite the thermostat cranked.

I’ve long ruminated on the source of his drinking and the vast inventory of usual suspects. The perilous escape from communist Vietnam, the generational trauma of displacement, the emotional disconnect from his westernized children, the cultural stigma associated with struggles with mental health and depression. An Australian study concluded that fifty percent of Vietnamese refugees were diagnosed with PTSD, while forty-eight to fifty-five percent have experienced long-term depression stemming from their migration experience.

I make the call. The chirp of the line drawn out and desolate. Voicemail. I can envision his phone lighting up and the maudlin eschewing of accepting the call due to the inevitable inquiries into his wellbeing and health. He doesn’t want to be a burden to anyone. Especially during the holidays. He’d prefer to be left alone and to his own memories of the silhouette that was once his homeland. And in doing so, he’s cinching the coat belt of resilience a little tighter around my waist, in the hopes that I can be better protected from the harsh realities swirling and incoming.

Tommy Vinh Buiis a librarian and doctoral student. He was a Peace Corps volunteer serving in Central Asia and a 2018-19 Arts for LA Cultural Policy Fellow for the City of Inglewood. His work can be found in the current exhibition at the Wende Museum Vietnam in Transition, 1976-present about the multi-layered intersection of arts, history and memory since the end of the Vietnam War.