The last time a total eclipse was visible in the U.S. was in 2017, nearly seven years ago, but for Southern California, it’s been over 100 years.

Eric Collins, CSUN Department of Physics & Astronomy lecturer, says the reason a total eclipse is rare for Angelenos is because the width of the moon’s shadow is small — about 50 miles wide.

“If you wanted to see a total eclipse, you would have to go where the shadow is,” Collins said.

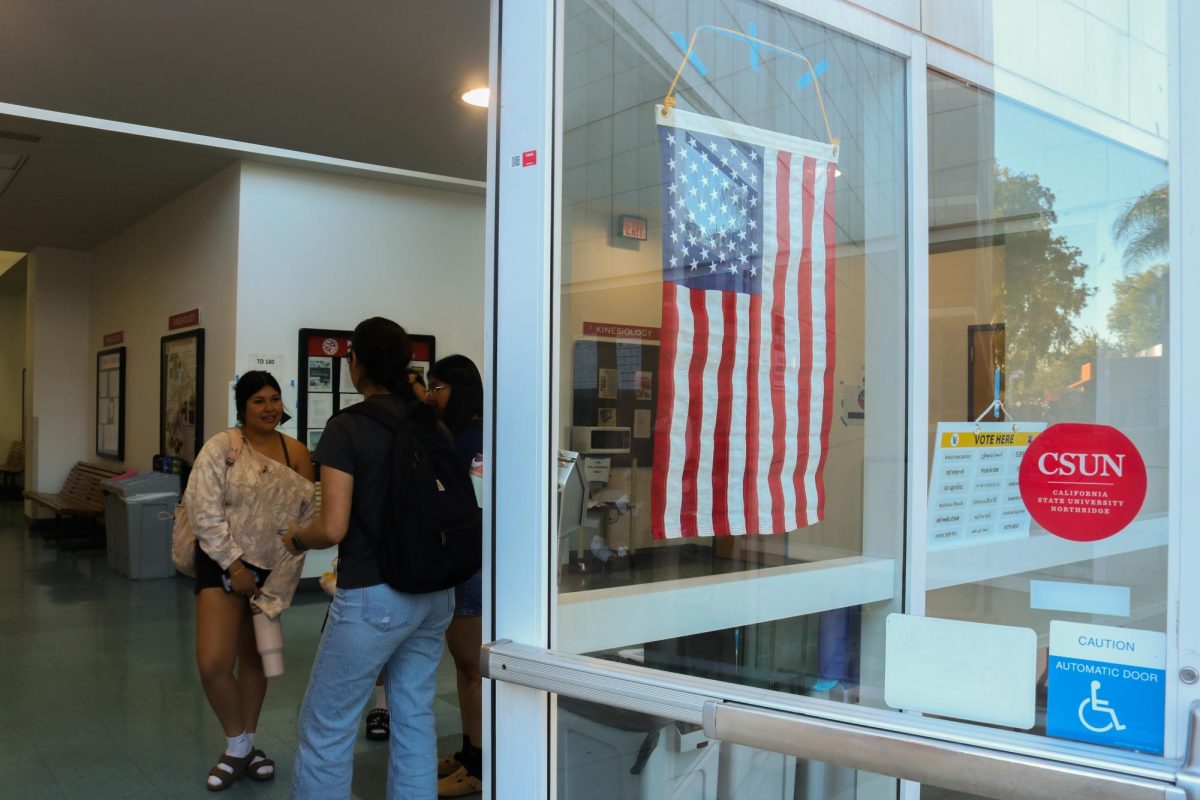

The CSUN Society of Physics Students, or SPS, and the physics and astronomy department hosted a Solar Eclipse Day viewing event Monday morning at the Donald E. Bianchi Planetarium from 10 a.m. to 12 p.m. Hundreds of students, staff and visitors lined up outside the planetarium to view the partial eclipse through a solar telescope provided by the department.

The eclipse’s path of totality, or areas where the total eclipse was visible, included Mexico, Canada and some parts of the southern and eastern coast of the U.S., according to NASA.

A total solar eclipse is when the moon passes in between the sun and the Earth, and blocks the face of the sun.

Tanner Rosenberg, CSUN Department of Physics & Astronomy instructional technician, guided spectators as they viewed the solar phenomenon through his department’s equipment.

Rosenberg said that the department’s telescope uses a hydrogen-alpha filter, making the sun appear red when looking through the lens, which is necessary for ensuring eye safety. He also said that this feature makes it easier to see details like sunspots and solar flares.

“[The] things that look like hair sticking off the side, those are particles, gasses that are being ejected from the sun by the sun’s magnetic fields,” Rosenberg said. “They sort of bubble out, and when those bubbles pop they can shoot these particles off, and that’s a solar flare.”

CSUN students like Anabell Torabyan were excited to view the partial solar eclipse through the telescope’s hydrogen-alpha filter.

“It’s really cool,” Torabyan said. “I got to see the flares of the sun, and one of the dark spots.”

Students were provided eclipse-viewing glasses by the Department of Physics & Astronomy, and were shown pinhole demonstrations to safely beam at the solar phenomenon.

Collins said the material used in the viewing glasses is similar to what’s used in welder’s glasses, and is what is needed to safely observe the eclipse.

In addition to the viewing of the eclipse, this year also marked the grand reopening of the planetarium and the return of their Friday night star shows.

While Los Angeles was only able to view a partial eclipse, other parts of the U.S. in the path of totality were able to observe a rare total eclipse. Prior to this year’s spectacle, the last total eclipse viewable from the country was in 2017, according to CBS News.

A New York Times article reported that the last time a total eclipse was visible in Southern California was in 1923, and is next expected to be visible again in 2045.

CSUN’s Society of Physics Students is one of hundreds nationwide that exists “to help [physics and astronomy] students transform themselves into contributing members of the professional community,” according to the group’s website.

The local chapter is led by President Xana Keating and Vice President Ani Papazyan, both astrophysics majors in CSUN’s physics program.

“SPS supports what we [did] today — bringing the community together, getting people excited about physics, and educating people outside of astrophysics about the solar eclipse,” Papazyan said.

Keating was particularly impressed with the large turnout, which included students, faculty, staff and members of the public.

“There was a middle school tour here… [as well as] families with little kids. It’s been a big community thing,” Keating said. “I definitely was surprised, I saw all my professors here. It’s amazing, even professors from the other departments as well. I think it’s cool to showcase what we do as a department and what kind of exciting things happen.”

Many students and staff who attended the viewing talked about the magnitude of the event as something that brought people together, even with all the issues going on in the world today.

“We’re all here on the planet, we all experience this, so this is universal to humans. To us,” Keating said. “It’s a moment for us to get together. That’s why I think it’s so amazing how many people came out. It’s a moment of unity.”