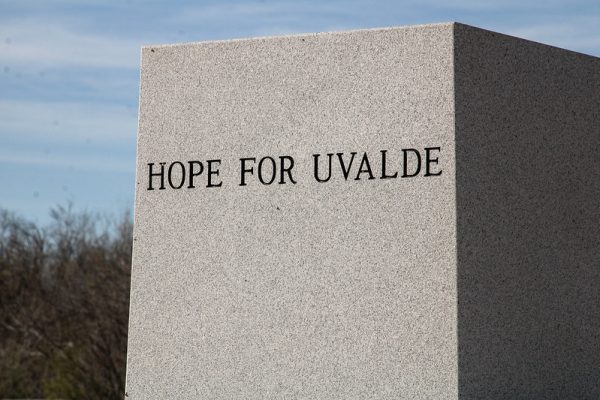

On a sunny and windy morning in Uvalde, sun beams illuminate crosses surrounding a water fountain in the middle of the town’s central plaza. Some of the crosses have been knocked down by the strong winds that blow through the town.

There are remembrances left by friends, families and strangers who have all felt the impact of the massacre in Uvalde on May 24, 2022, when 21 lives were cut short by an 18-year-old with a military-grade weapon.

Rocks can be found at the base of each cross. Painted different colors, they carry a common message: “Too beautiful for Earth.”

The walls of the businesses surrounding the town plaza are painted with the portraits of the victims. The murals are beautiful, full of color, showing off the victims’ personalities. Each has a trifold-shaped memorial with the words “In Loving Memory,” adorned with candle-holders and trinkets left by friends and family members.

The mural of Xavier Lopez illustrates his love for music, his excellence in school, and his romance for classmate, Annabell Rodriguez whose mural stands right next to his.

Annabells’ mural symbolized her colorful nature by including a blue butterfly. She had a love for creating TikToks and the cravings for spicy foods.

A heavy feeling is inescapable looking at the children’s portraits, as well as the crosses with beautiful messages left by their loved ones. The sound of the water falling from the nearby fountain eases the pain of it all.

There are more than 4,000 students in the Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District in a city with more than 15,000 people. About 7% of Uvalde County’s population are children under 5 years old, and about 28% are under the age of 18.

The psychological effects children endure after a traumatic event are profound, and with Texas ranked 51st in the country for access to mental health, Uvalde was not prepared. Today, the children of Uvalde are not OK. Resources have poured in, but they may not have been enough.

Many Uvalde children are losing sleep, having night terrors and suffering from a loss of appetite, according to Brenda Faulkner, the director of the Children’s Bereavement Center, one of the mental health resources available.

Faulkner is a fairly tall woman with dirty blonde-reddish hair and bangs covering her forehead. Her blue eyes shine with a kindness and compassion that give the impression she is always speaking with a smile.

The students often refuse to go to school, said Faulkner, who also serves as one of the counselors at the center.

“They want to be children again,” Faulkner said with tears in her eyes, “and probably one of the big losses is certainly their innocence and their childhood.”

The impact of trauma on children

The enduring impacts of gun violence on children — those most vulnerable to the psychological reverberations of gun violence — are profound and multifaceted. Dr. Arash Javanbakht, a leading expert on trauma, has studied those effects. His work offers a crucial perspective on the issue of post-catastrophe childhood trauma.

Children who have been exposed to traumatic events often experience a state of hyperawareness that can be overwhelming, Javanbakht said. Even the sounds of celebration morph into triggers of profound anxiety.

“A mere backfire of a car or the sharp pop of fireworks can spiral them back into the terror of the moment, a relentless reminder of their ordeal,” Javanbakht said.

But heightened vigilance is just the tip of the iceberg, he added. Pervasive negative emotions can skew a child’s perception, casting long shadows over their sense of security.

“The world, through their eyes, becomes a tableau of threats, each more menacing than the last,” Javanbakht said.

In Uvalde, just 30 miles from the Eagle Pass border crossing, the wailing sirens and the red, white and blue beams of lights from U.S. Customs and Border Patrol agents chasing vehicles suspected of carrying undocumented migrants can also act as triggers.

The chases are called “bailouts” because when the vehicle eventually stops, or crashes, the occupants bail out and scatter. These incidents put Uvalde’s schools in a state of lockdown, the same response it would have for an active shooter.

Prior to the mass shooting, the number of bailouts increased significantly in Uvalde, prompting dozens of lockdowns, including on the morning of the mass shooting.

Students became desensitized to the frequent incidents prior to the massacre. Today the sirens threaten to retraumatize them.

Psychological burdens don’t end with altered perceptions and anxiety. Survivor’s guilt emerges as a crippling force, compelling young survivors to wrestle with burdensome questions about why they survived when others perished. “Why me?” becomes a recurring refrain, adding emotional weight to their already fragile psyches.

Dealing with the Emotional Aftermath

Trauma survivors also develop an intense fear of separation, Javanbakht said. “The anxiety of losing another loved one becomes a pervasive specter, one that clings tightly and stirs panic at the thought of parting, even if briefly.”

Javanbakht said that these problems can develop from their depression and ultimately interfere with an ability to perform typical childhood activities.

“Trauma-induced depression is particularly insidious,” Javanbakht said, “as it stealthily compromises various aspects of a child’s life, from school performance to social interactions.”

Given these profound challenges, towns like Uvalde need resources to address the mental health needs of its young people. The community’s response, including counseling services and outreach programs, is critical in determining the path to recovery.

“Recovery is communal,” Javanbakht emphasized. “Schools and community groups are instrumental in orchestrating a supportive atmosphere that fosters healing. Group-based interventions, in particular, can reinforce feelings of safety and rebuild the sense of control that trauma seeks to destroy.”

Javanbakht’s work shines a light on the crucial support necessary for the psychological recovery of children post-trauma. In the aftermath of such tragedy, the collective effort to ensure that no child navigates their trauma in solitude is essential.

John Woodrow Cox is a staff writer at the Washington Post who has studied gun violence and the threat it poses to the country. Cox said the harsh reality of the new American culture, which has seen more than 400 school shootings since Columbine in 1999, can create trauma and fear in children. The anxiety they have to endure just going to school can be devastating, he said.

“There really is nowhere we could go where we feel like we won’t experience that, including churches and movie theaters, obviously schools, malls,” Cox continued, “There’s nowhere a gun might not show up.”

With each new school shooting, the fear that this may happen at any school undermines the idea of school as a place where children feel safe.

“Often we only assess the severity of a shooting or gun violence in America by how many people die. But that number is huge. It’s enormous,” he said. “But it ignores the people who were wounded and didn’t die.

“It ignores all the people who witnessed gun violence,” he continued. “It ignores the people who lost someone to gun violence. It ignores children in schools where lockdowns occur. It ignores children in schools where actual school shootings occurred, but those kids were not physically harmed.”

Uvalde: Crisis in a Mental Health Desert

Texas is known for issues of access to health services, particularly in rural areas like Uvalde.

The state has one of the nation’s highest percentages of uninsured residents, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

About 18% of residents are uninsured statewide, which includes nearly 19% of the city of Uvalde, and 24% of Uvalde County, according to Census data. The national average is around 8%.

Data from the Texas Department of State Health found that 98% of all counties in Texas have a shortage of mental health professionals. Two-thirds of Texas’ licensed psychologists and over half of the states’ licensed psychiatrists and social workers work in urban areas.

The people seeking mental health resources in rural areas are left having to travel long distances to get professional care, leaving small towns like Uvalde traveling over an hour and a half to secure the help they need.

Residents’ economic resources are also a challenge. About 20% of Uvalde’s population lives below the poverty line, including 39% of children. The national average is about 12.5%, according to data from the Census Bureau.

The city received an outpouring of support that coalesced for the children in the form of a therapy center, community events and other activities meant to help the survivors feel normalcy. The Children’s Bereavement Center is a small white building down the block from the plaza lined with the children’s crosses dedicated to this purpose.

The center serves all South Texans between the ages of 3 and 24 affected by a loss of a family member or loved one by providing ongoing support groups, individual and family counseling, and professional education and training programs.

With the help of donors like Georgia Pacific and several communities in the San Antonio area, the center opened up June 23, 2023, a year after the tragedy, in a renovated space near St. Philips Episocpal Church, which donated the building.

Faulkner said the Children’s Bereavement Center expanded its mission in Uvalde to include anyone who was affected by the shooting. The center provides grief therapy using a counseling model created by psychologist William Worden, she added.

Worden established a framework of four tasks to help people through their grief. The first task is to accept the reality of loss. Next is to process the pain of grief, followed by adjustment to a world without the deceased. The final task is to find an enduring connection with the deceased in the midst of embarking on a new life.

The ultimate goal of the bereavement center is to help people recognize and understand the grief they are going through, to stabilize and preserve family relationships, and develop healthy coping skills after the death of a loved one, Faulkner said.

Healing in Stages

Physical activity and outdoor play has become a crucial part in the healing process for the children.

“We do a lot of expressive arts with them. We’ll play games with them. We have journals that we do with them just to get them talking,” Faulkner said. “The biggest service we provide is giving them 45 minutes to an hour. And it’s all about them. It’s not about their deceased cousin or sister or brother or the shooting or school. It’s all about them, what’s going on.”

Faulkner described one shooting survivor who was nonverbal at home, but when the child’s mother asked if he spoke during therapy, the answer was always yes, Faulkner said.

“He’s getting more and more familiar. He didn’t want to be away from his mom the first time. And so it’s his time. He comes at 6 p.m. in the evening and he walks in the front door with this huge smile on his face. I’ll ask him something, and he’ll go, ‘Mmm,’ until we get into whatever play activity or whatever art activity,” Faulkner said.

Play wasn’t originally part of the therapeutic response because many Robb students had to run across a playground to get to safety that day. But outdoor play was added to their recovery journey when the center held a “grief” camp that reunited dozens of children who were students at Robb Elementary.

The four-day camp allowed children to engage in expressive arts, music and sports. NBA point guard, Tre Jones, of the San Antonio Spurs donated $25,000 to the center during the camp’s sports day.

The children participated in a half-day basketball clinic held by the Spurs. They shot some hoops with the players and received plenty of memorabilia and autographed goodies.

“The giggling and the laughing — it was just a beautiful thing to see. And their favorite thing to do at a grief camp, because you can imagine, was playing outside. They wore out two wiffle ball sets because they wanted to be together and they wanted to play,” Faulkner said with a smile.

Thinking about helping the children left her choked up.

“Very few people get the opportunity to do their life’s work, and I’m getting that opportunity. I couldn’t be more blessed for it,” Faulkner said, as she wiped the tears falling down her cheek.

Raising Awareness

Hector Gonzales, president of Southwest Texas Junior College, sat in his swivel chair behind a large square desk. Behind him was a framed picture that read, “Restore you and make you strong,” something the people of Uvalde have been trying to do for two years now.

Gonzales talked about the camp he created for children and a fair where families could learn about the help that’s out there for them.

“Uvalde is a tight-knit community — the shooting hit a small community hard and impacted everybody and everything,” said Gonzales.

The college hosted a resource fair in June 2022, intending to help a community grieving and looking for ways to cope, with hundreds of people attending.

Gonzales said the idea was to make sure the people of the community knew about the resources available.

“We realized that there was no assistance for these families. We tried to bring resources, money for those who couldn’t go back to work because their kids couldn’t be left alone,” he said.

Finding a Safe Space for Survivors, Families

Driving east on Highway 90, which serves as Uvalde’s Main Street, fields can be seen on the left, and the Tabernacle of Worship, pastored by the Rev. Daniel Myers, on the right.

A cold wind hits a visitor’s face just outside the door, but warm air envelopes upon entering Myers’ tabernacle, where many families of the survivors have found support.

It’s a nontraditional church setting — instead of a giant cross on top, the barn-like structure bears a flag on its gate that reads “One Nation Under God.”

Inside, the room is divided in half. On one side are tables for people to sit and eat, like a small hole-in-the-wall restaurant, with a few booths and tables in the center.

On the other is where the worship takes place. The podium where the pastor stands is in the middle with chairs surrounding it, leaving an aisle for people to walk through. An American flag hangs on one of the walls near a huge cross and a thorny crown. Next to that is a picture that reads “Fly High” above the 21 portraits of the lives taken May 24, 2022.

Myers used to be a pastor in Phoenix but moved back to Uvalde with his wife, eventually assuming a voice he never thought he’d have.

After the shooting, Myers was critical of Uvalde police officers, who began to tail him after he started questioning the actions of the police commissioner and the task force that responded on the day of the shooting. “They were following me around,” Myers said, adding it took a call to the mayor to get the police to stop.

“I’m the only pastor in Uvalde that sticks out like a sore thumb,” he said. “I’ve lost friends standing up and speaking for the children.”

For two years now, Myers has not stopped using his voice for the victims and the survivors, he said. He attends meetings about the massacre and supports the families by making sure they are aware his services are always available to them whenever.

He did not want to take advantage of their vulnerability or push his beliefs on those that were grieving, he said. He told them that he is there for them and if they want a prayer, or for the pastor to visit their house, he’s there.

“I don’t know their pain, but I stand with them and their pain,” said Myers.

Brett Cross and his wife, Nikki — the parents of Uziyah Garcia, one of the victims — walked into the tabernacle, and once Myers saw them, tears formed instantly.

He hugged them both and said, “This is your house; this is your house.”

Myers held a dinner for the survivors and the family members of the victims just to let them know that he, his wife and the church would always be there to support them with anything they needed. He also has hosted professionals, like psychologists, to talk to those who were grieving.

Myers knows the children of Uvalde are still suffering. He hears it from those who have turned to him for words of affirmation through their healing process.

“Kids, 9, 10 years old are wetting the bed,” Myers said. “They go out as a family and the child would see somebody that would remind them of the shooter and they would just say, ‘I want to go home’ — just loud noises, anything, ‘I want to go home,’ and that hurts,” Myers said, with tears in his eyes.

The door to his tabernacle remains open for those who are grieving and are looking for support as the small town of Uvalde is still on the journey towards recovery.

“Where are we safe now?” Myers asked. “We’re not safe anymore.”

Healing with Art

Many have struggled to find a safe place, especially the families of the victims and survivors, but they have found comfort around the community in places where they can commemorate those they love and lost.

Abel Ortiz is a Mexican-born artist who lives in Uvalde. He owns an art gallery whose mission is to bring art to rural cities, Ortiz said.

Ortiz strongly believes that images have power and that they send a message to the heart. He believes that art is therapeutic, which is the reason why he was responsible for the murals painted around Uvalde, commemorating the lives lost in the tragic shooting.

“I have to do something about this too,” Ortiz said to himself after the shooting, “I want to help the community.”

He had the help of artists from around the country who also felt like they needed to do something to help Uvalde recover.

Their contribution became the children’s portraits that surround the town plaza.

The murals are intended to help the families heal, and Ortiz feels like they are working. Families are always seen at the murals of their children; some may be having dinner or their morning coffee in front of the murals.

“There is always something new in front of the murals,” said Ortiz, “The murals have a lasting power to keep healing.”