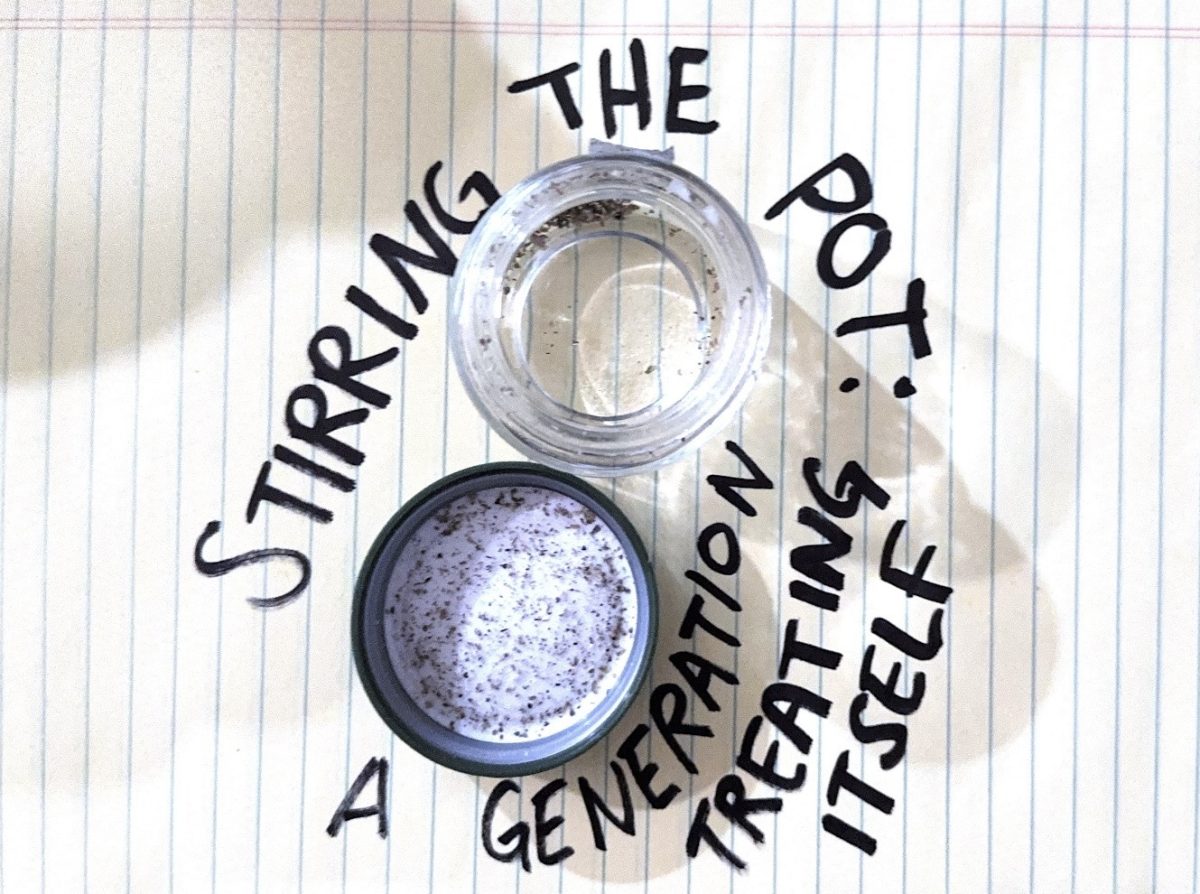

The previous edition of “Stirring the Pot” explored how undocumented immigrants are turning to cannabis as a lifeline – a way to manage chronic pain and anxiety when formal healthcare is out of reach. However, that struggle isn’t isolated. Rising costs, systemic mistrust and institutional neglect now ripple across the broader working class.

This next chapter widens the frame to reveal how cannabis has quietly become a stand-in for care among Americans who can’t afford, or no longer believe in, the traditional healthcare system.

As weed legalization spreads and dispensaries multiply, a collision is unfolding between access and oversight. What began as a last resort for people like Alondra’s mother, who used marijuana to ease endometriosis pain while avoiding the risks of formal care, has evolved into a nationwide pattern: young, uninsured and overworked Americans turning to cannabis not for pleasure, but for relief.

Dispensaries, once branded as lifestyle destinations, are now functioning as informal health outposts; spaces where people seek control in the absence of medical trust.

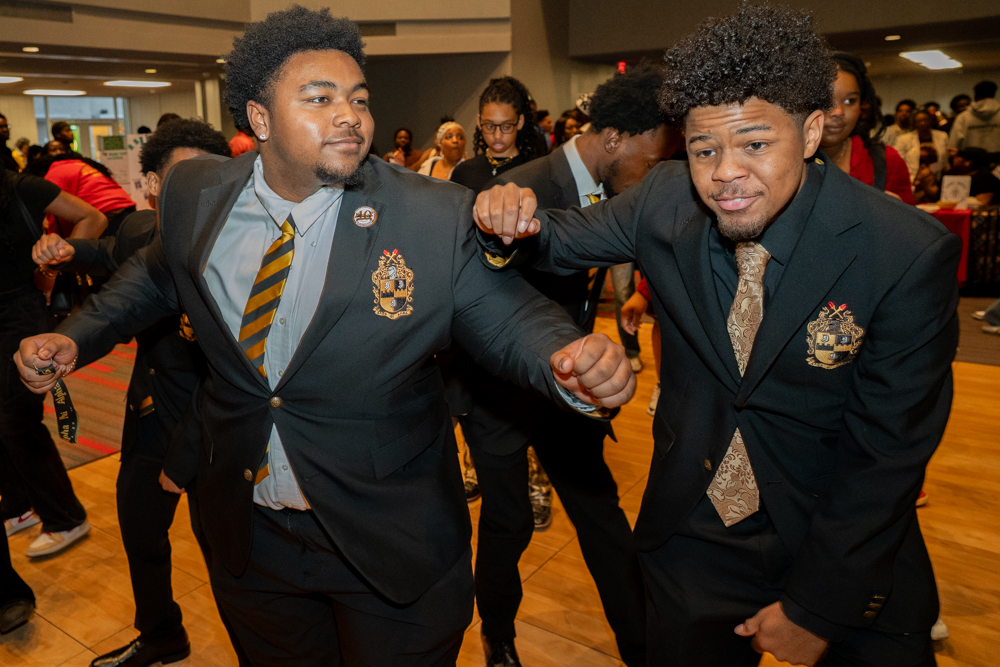

Rose and Marley, who agreed to be interviewed only with pseudonyms out of privacy concerns, embody this growing demographic.

For Rose, cannabis began as a last resort. Struggling with anorexia in her late teens, she had tried every appetite stimulant doctors could prescribe. Nothing worked.

“I wasn’t trying to get high,” she said. “I was just desperate to feel normal.”

At 19 years old, a friend handed her a weed vape before dinner.

“Weed helped me eat,” Rose said. “It got food down without coming back up. The pills made me nauseous, but that night, it was the first time in weeks I didn’t gag while chewing.”

What started as a moment of reprieve spiraled into dependence. Rose developed Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS), a condition triggered by long-term cannabis use. This left her in cycles of nausea and vomiting, the same symptoms she was trying to escape. Still, the comfort cannabis gave her – its portability, familiarity and its ability to quiet anxiety and restore appetite – was hard to surrender.

Marley’s dependence stems less from illness and more from mistrust. As a freelance art director without health insurance, she described Western medicine as “aggressive, expensive and one-size-fits-all.”

“You go in with stress or a headache and come out with pills you’re supposed to take forever,” she said. “Weed feels gentler. It gives me space to feel things instead of muting them.”

Her cabinet is lined with herbs, tinctures and homemade remedies; parsley and papaya blended into smoothies instead of over-the-counter solutions.

“It’s not that I don’t believe in medicine,” Marley said. “I just don’t trust what it’s become. As a freelancer, your health becomes something you manage, not something you treat.”

Marly noted the accessibility of marijuana, as well as the functionality and flexibility of its effects.

Together, their stories expose a widening public health paradox. Cannabis, once criminalized and taboo, is now a form of care for the neglected. Yet, as its therapeutic promise expands, regulation and guidance lag far behind. A growing share of Americans, including immigrants, freelancers and uninsured twenty-somethings, are managing their pain in the shadows of legalization.

The result is a quiet dependence that sits at the intersection of economic precarity and public health; a generation medicating itself, not out of rebellion but out of resignation. As cannabis continues to straddle the line between recreation and remedy, its role in American life reveals something deeper than cultural acceptance; it exposes a broken system.

For many, weed isn’t a vice or a trend, but a stand-in for care they can’t afford or trust. Those excluded from the healthcare system, the undocumented, the uninsured and the underpaid are self-medicating through pain in a country where relief has become a privilege.

In the U.S., where a doctor’s visit costs more than rent, young generations are learning to heal themselves one puff at a time.