A study shows that polling stations, where citizens are assigned to go vote during election season, are not as neutral as the public believes them to be.

CSUN professor Dr. Abraham Rutchick, who conducted the study, found that a citizen’s vote can be impacted by where he or she goes to vote.

“Our usual assumption is that it doesn’t really matter where you vote,” Rutchick said. “It matters what you’re thinking and what the candidates said and various other things(…)so, you go and vote for whoever you want and it doesn’t matter where you go.”

As Rutchick started taking more psychology classes in the university, he said he started to learn how subtle factors can have a significant impact.

The notion that a polling station’s location can influence voting was sparked during the Fall 2004 elections.

Rutchick was assigned to a polling station held at a church in Santa Barbara.

“I remember looking up at the steeple and just thinking to myself, ‘wait a minute,’ this means something,” he said. “It struck me that churches are not just rooms. They are very special places that mean a lot to a lot of people. They’re linked to morals, values and ideas.”

“It can activate different ideas, that walking into a place can make you feel different,” he added.

From 2004 to 2007, Rutchick did two studies from South Carolina voting data. He collected data that showed all the precincts and how people voted in each precinct. He then assorted everything into churches and non-churches.

“It’s really just a bunch of hunting around,” Rutchick said.

Rutchick also surveyed people in Santa Barbara, asking them what their political values are and what Christian values meant to them in a political context.

He found that “no matter how conservative a particular individual was, they thought Christian values were even more conservative, so someone who is fairly liberal thinks the Christian values are a little more conservative than them.”

Rutchick also found that people who are consider themselves “quite conservative” also think that the Christian values are more conservative than them.

“Of course, not all Christians are conservative obviously,” Rutchick said. “People seem to think that this concept of Christian values is conservative(…)Voting in a church might make you be more conservative particularly with respect to issues that seem related to it, specifically abortion and gay marriage.”

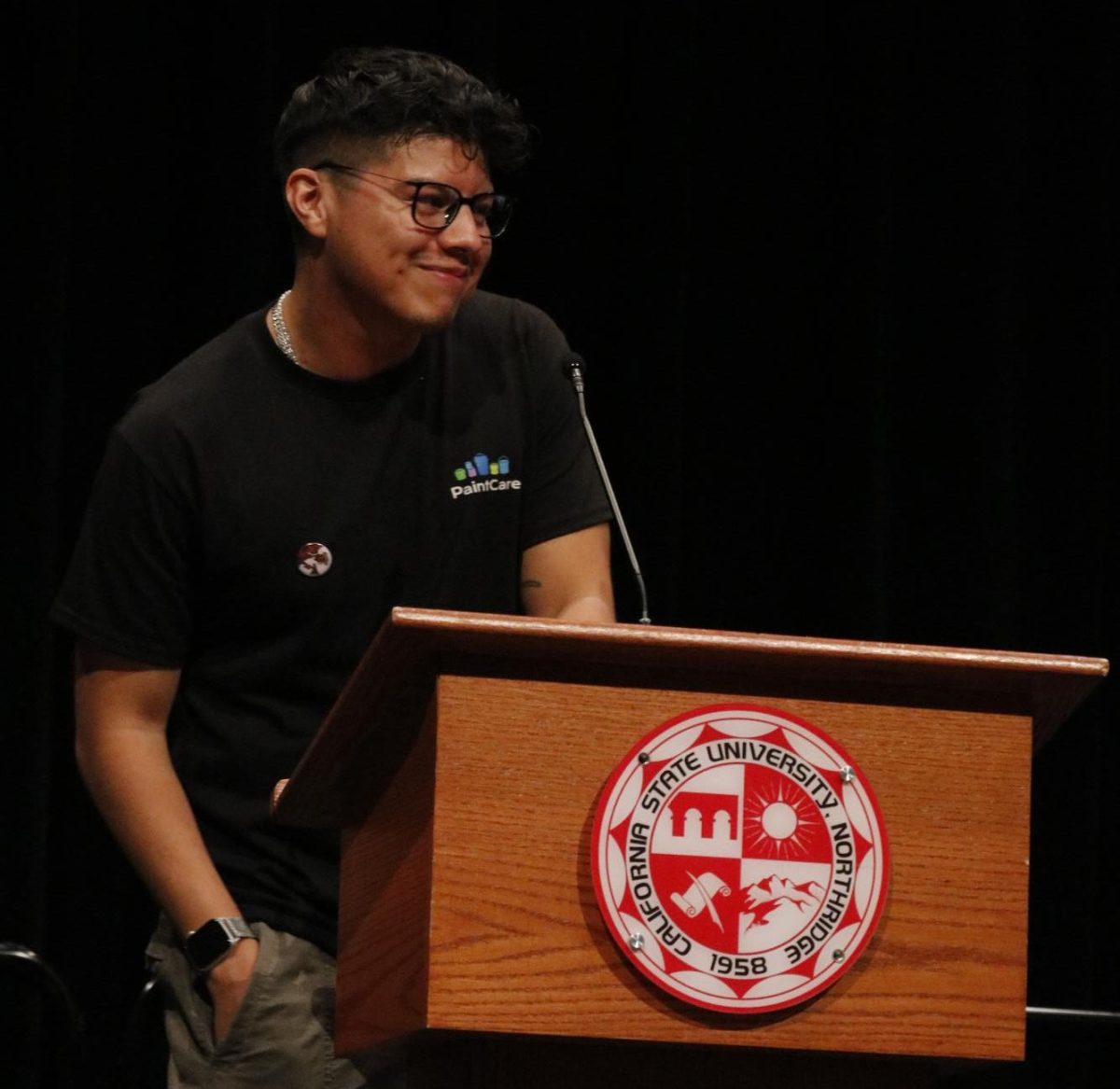

Jonathan Polus, Associated Students senator of humanities said he can understand why people are influenced.

However, “if you have done your research, if you have done due diligence and figuring out what the issues are, then when you go into a polling station, it’s not going to affect your vote,” Polus said.

“Maybe you walk into a polling station within a church and people who volunteers there are Christians and guess what, because they’re actually nice and smiling at you, you vote better,” Polus said. “You vote for more conservative things.”

Polus said that this was the only way he could see this type of influence.

“It’s up to you if you want to vote,” said Sophomore Joanna Retana, 19. “You make the decision whether you want to make a difference or not.”

Retana, an accounting major, said she believes a polling station can influence a person, depending on whether that person lives in a democratic or republican area and on the campaign advertisements.

For the upcoming elections, she said the polling station would not influence her vote.

“If I know who I’m voting for, I’m going to be focused on the reasons why or why not, not on other advertisements or what other people say,” Retana said.

Rutchick said it’s challenging to say how this study will affect the upcoming election.

“For instance, with Meg Whitman and Jerry Brown, Meg Whitman is more conservative but Jerry Brown used to be in a seminary,” Rutchick said.

“So, it’s not necessarily clear what the impact of churches would be,” Rutchick added.

“We are subject to influences to which we are not aware,” Rutchick said. “I’m not saying that it always happens, but I think I’ve demonstrated that it can happen.”

Rutchick’s work was published in “Political Psychology” in January 2010.