>>Updated with additional information.

Levon Yotnakhparian did not expect his revered lifestyle as a soldier to evolve into a tale of betrayal, escape and the salvation of thousands during the Armenian Genocide.

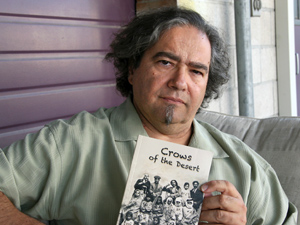

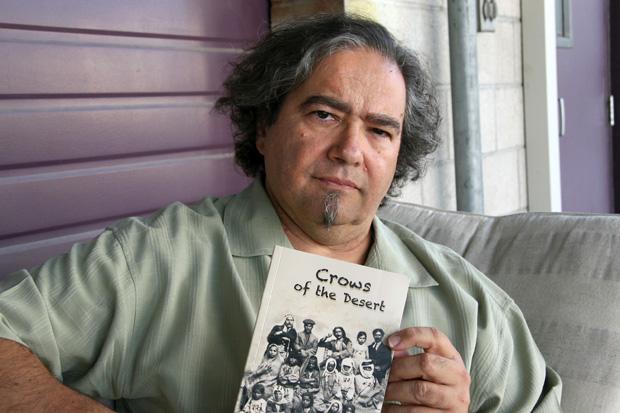

Levon Parian, Yotnakhparian’s grandson and a professor of art photography at CSUN, collected pictures, letters and stories from other family members for three years before publishing his grandfather’s memoirs in “Crows of the Desert” earlier this year. The historical story reflects Yotnakhparian’s life-saving journey.

“People are wondering where it has been all this time, and why haven’t they heard of this,” Parian said.

Before his death, Yotnakhparian dictated the story to his wife, who took the writings to a novelist. who changed the factual history, and left the author unsatisfied.

Parian decided to publish the facts at the request of his late father.

When Yotnakhparian enlisted in the Ottoman cavalry, he had no idea that history would change before his eyes as the Turks turned on his people. According to Parian’s publication, reformers known as the Young Turks overthrew Ottoman rule and systematically changed the way the empire was run. Rather than granting civil rights to those in the empire, the Turks were determined to “Turkify” every person.

Once the Turks were convinced that the Armenians must be killed, they went after the Armenian population.

“He saw the transformation,” Parian said. “Armenian soldiers were highly regarded, and next thing you know they are being put into work camps – work details to be killed. He’s lucky he found people that were good that wanted to take care of him and protect him.”

He decided to pay it forward by escaping from the military and headed to Jabal al-Druze — now present-day Syria. After receiving help from leaders of the Arab Revolt in Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and other eastern regions, Yotnakhparian made it his mission to save the oppressed Armenian survivors and orphans after his escape. His grandson said that his late grandfather rescued over 4,000 people.

These protectors offered him services that even officials could not obtain including documents to stop trains so that Yotnakhparian could transport the rescued orphans, according to Parian.

“These people knew that if they (the Armenians) didn’t win, they would see everyone in their family slaughtered. A different kind of mentality forms when you know that everybody is going to die than when you’re the aggressor,” Parian said.

The current Turkish government has not recognized this event as a genocide. According to Parian, the term “genocide” was coined in 1943 by Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin, to describe the Armenian killings.

Dr. Vahram Shemmassian, a professor of Armenian studies classes under CSUN’s modern and classical languages and literatures department, has done research on survivors of the genocide and the difficulty they encountered. He teaches about the genocide for at least one week in each class, and some students write their research papers on the topic.

“Every Armenian feels the burden on their shoulders because of the lack of recognition and because each and every one of us has a story to tell. It’s a living testimony. We have felt it in our own skins,” Shemmassian said.

According to Shemmassian, approximately 80 percent of Armenian studies students have an Armenian heritage. Of that group, 95 percent came from public schools where Armenian heritage and culture are rarely taught. The nearly 30-year-old Armenian studies concentration in the department teaches students about Armenian heritage because it affects all of humanity, according to Shemmassian.

“The Armenian Genocide, as is the case with the Holocaust or Darfur in the Sudan or Cambodia or any genocide, is a crime against humanity,” said Shemmassian. “Since we are a part of humanity and another group of humanity is perpetrating this reprehensible, incomprehensible heinous crime, part of humanity is being affected.”

Shemmassian said that he was one of the first people to purchase the English version of “Crows of the Desert,” and he used some of the information from the original Armenian version to do research a few years ago. He uses some of the concepts in the book to describe the relevancy of the genocide in today’s society.

Parian will be speaking about the book at 7 p.m. on Oct. 11 at the Glendale Central Library. The lecture will be in English, and admission is free.