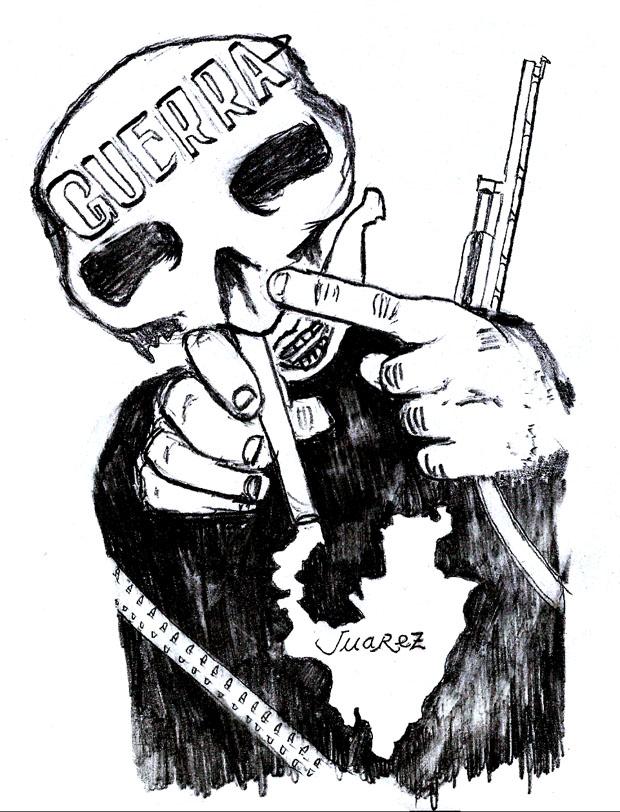

Ciudad Juárez.

Its very mention connotes images of shootouts in the streets, bodies lying on the roads, mass graves and newspapers filled with the photographs of yet another score of young men and women gone missing in what once made Juárez the murder capital of the world.

The Juárez I describe is not the Juárez that has always existed. My parents describe “el Juárez de ayer,” the Juárez of yesterday, replete with dance clubs, movie theaters and bars.

They describe a Juárez where it once snowed, a Juárez where the streets were once clean, and where you could take the bus anywhere for only a few pesos.

When I hear Juárez, I flash back to images of my cousins and me running down Avenida Mariscal, causing nothing but mayhem in the neighborhood just a stone’s throw away from Zona Centro — downtown.

I remember holiday visits toasting tortillas on top of my grandmother’s petroleum-powered heater, or adding water to the washing-machine sized air conditioner in the living room during our summer visits — it was so powerful, it would suck the electricity from the neighboring houses.

But Ciudad Juárez has now become synonymous with drug cartel wars. So what are the so-called “drug wars?” Why is it considered many wars and not just one? Who were the belligerents? And why, most importantly, have so many people been killed?

To attempt to understand this, we must go back to late 2006 when then-Mexican President Felipe Calderon declared “war” — his words — against the drug cartels, many of whom continue to be responsible for much of the drug flow into the United States.

Calderon had just been elected. His ascension to the presidency represented a victory for his Partido Acción Nacional (National Action Party, or PAN) after 71 years of rule by the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI).

As one of his first acts in office, Calderon promised to crack down on the violent cartels — who, at the time of his election, had killed 2,119 people — by using the military in order to circumvent possible corruption among police ranks.

The plan backfired. Shootouts between the military and cartels were almost a daily occurrence. Collateral damage from these shootings resulted in many deaths. Open season was declared on the Mexican people as assassins did not discriminate against those they were looking for or those who got in the way.

By the time 2010 rolled around, 15,273 have been killed — mostly innocents, but also people involved in the drug trade, according to the Mexican government.

The “drug wars” are called such because they involve the numerous drug cartels spread across Mexico who continue fighting to this day — albeit minimally — for control of the lucrative drug trafficking routes into the United States. Many of these routes before entering the United States have points in border cities such as Tijuana/San Diego; El Paso, Texas/Ciudad Juárez; and Nuevo Laredo/Laredo, Texas.

Why am I writing about this now? Mexico is recovering.

A new Mexican president — Enrique Peña Nieto — was elected in 2012. His administration’s goal is to take a less conspicuous role in the fight against the drug cartels, an about face from his predecessor’s tactics, by pulling out the military’s involvement in the fight, although some argue the fight is just as intense. Peña Nieto instead hopes to focus his efforts on education, fiscal and energy reforms, according to an article in the Huffington Post.

Mexico recently celebrated its independence on Sept. 16. Across Mexico, news of decreasing violence continues to be the story of the day. No longer are the media filled with daily death counts. The news is no longer that a death has not occurred in 24 hours.

In Ciudad Juárez proper, a sort of “renaissance,” according to newspapers such as El Diario de Juárez, is taking place. Tourists are once again visiting the city, pumping the Juárez economy with much needed American dollars.

Juárez’s nightlife is blossoming once more. People are returning to bars and nightclubs without fear of being gunned down while sipping a cocktail.

Some argue that Juárez’s, and to a greater extent, Mexico’s resurgence, is a result of Peña Nieto’s scaled back attempts of combating the drug cartels. But others argue that the decrease in violence is a result of the fact that there is no one for the drug cartels to fight. As of 2013, the Sinaloa Cartel, run by notorious drug boss Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, controls many of the drug routes into the United States, which span the states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and the Mexican states of Sinaloa, Sonora, Chihuahua and Baja California, among others — a distance of more than 300 miles. Guzmán’s cartel — over time, and violently, at the expense of many lives — seized control of the routes from rival Juárez Cartel. The widely reported violence between the two cartels represents only one chapter in the bloody wars among other drug factions across Mexico.

Mexico is coming back. The drug wars are a bloody chapter in a country whose history spans thousands of years. But it is only one chapter in this long, storied and classical history. As such, I believe the country will recover and blossom once again.

I am proud to call myself the son of Mexican immigrants. I believe that the best of Mexico is yet to come. Although it will be a difficult resurgence, I believe the splendor, beauty, culture, and people, will once again make headlines instead of news about the latest shootout in the street, mass murder, or missing young man or woman. It will once again be the Juárez my parents grew up in and remember.