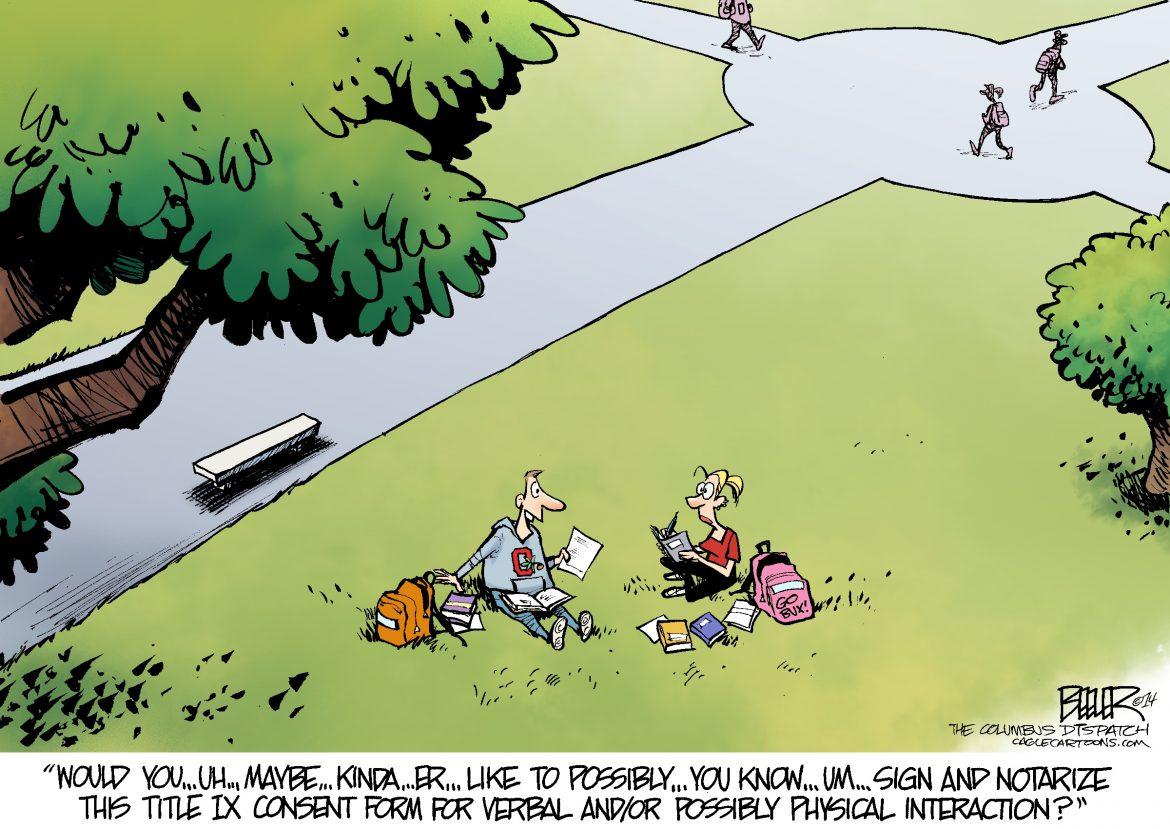

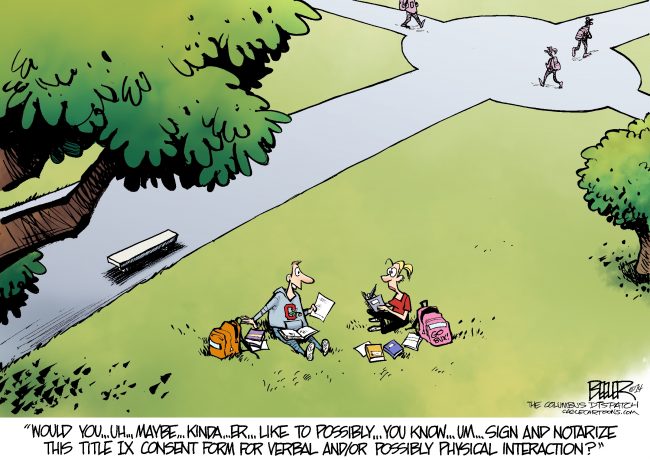

In September, Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill that made California the first state to adopt a “Yes Means Yes” policy. Simply stated, the former “lack of the word ‘no’” doesn’t imply consent.

Under this new law, any campus in the state must abide by certain policies and provide their strategies for dealing with rape allegations in order to receive funds.

Congratulations, California. You’ve cracked the code. That’s what we’ve been missing. A law of mutual consent.

Despite my remarks, I actually don’t have a problem with the new rule. I like the fact that we’re trying to make it more clear so no one gets confused. But do you see the problem here? We’re trying to dumb it down so that aggressors don’t get confused if and when they are raping someone.

Let’s be clear. We have always needed mutual consent or else it’s considered rape. If you are having sex with someone who doesn’t want to have sex with you, it’s rape.

Our problem here is in two parts. First and foremost, how can we even fathom “Yes Means Yes” when no one was even paying attention to “no means no.”

A West Virginia student’s story was recently squashed, after being gang raped by seven fraternity brothers. Seven people agreed to be in the same room and violate a woman for hours, and leave her bloodied. Seven.

We are far beyond discussing mutual consent.

Let’s discuss the university system first. This student trusted superiors to report the incident while having to remain in school for years with her perpetrators. This is eternally traumatizing to the victim, and dangerous to an entire student population.

In fact, it did affect others in the University of Virginia (UVA) case, as many have reported themselves victims at the hands of the same fraternity.

I was hoping the new “Yes Means Yes” law would answer some questions about delay in action when dealing with sexual assault cases. However, I don’t see anything specific about the amount of time a university has to respond, nor do I see anything concrete regarding the type of protection needed for a victim who has come forward.

The new law does say the university has to provide a strategy. It just doesn’t say which guidelines are acceptable in order to receive funds. It also states that the victim’s identity will be kept confidential, but it doesn’t say how it will keep aggressors from revealing this information.

I strongly believe that there should be an absolute fast track on sexual assault cases. There is no reason a victim should have to face aggressors while getting an education. How does the new law encourage victims to come forward if it may take years for action?

Furthermore, if colleges need to protect their reputation, are they really on the side of the student?

The UVA case implies no. Also, the 86 universities currently reported to be under federal investigation also implies no.

Harvard and Princeton are among those campuses being investigated, which suggests that money and privilege may easily trump a single student’s well-being. And let’s not forget the Columbia student who had to drag her mattress around campus to take a stand against sexual assault after the system failed her.

It was also noted that the UVA victim’s friends and fellow students failed her. I couldn’t believe how many people told her not to go to the hospital or to not report the incident because it would make future years harder for her, for the fraternity and all other greeks, and for the university as a whole.

This brings me to part two: the “bro code” and education within a pack mentality.

So many things that wouldn’t normally be acceptable happen because of people in groups. Peer pressure. It’s still a thing.

I can’t even find seven people to have dinner with, much less find seven people to rape someone with. We must start looking into why and how these things are taking place if we wish to stop them.

Society has always put a lot of stress on victims: Don’t dress to give the wrong impression. Don’t drink or put yourself in a bad situation. Here’s a nail polish that can help you prevent rape.

This “rape prevention” method transfers responsibility from the aggressor to victim and is also known as “victim blaming.”

CSUN’s own DATE Project website has guidelines for women to prevent from getting raped, but doesn’t explain anything about students stepping in when they witness sexual assault.

And while I understand and respect the intentions outlined on the website, the main goal should be to keep people from raping, not teaching people that they can help themselves to not get raped.

Where is the education to change our culture?

NPR released a great radio segment in August called “The Power of the Peer Group in Preventing Campus Rape.”

In this story, Oklahoma State University researcher, John Foubert, explains how men of college age often depend on the opinion of other men more than anything else, and that actions become more widely acceptable when everyone joins.

Many subjects in Foubert’s study found it normal to lure women to parties, and eventually have sex with them, by using punch or other alcohol. Many of the men admitted to either engaging in sexist conversation after their “hookups” or simply remaining silent.

Remaining silent or going with the group is the worst thing you can do.

Here at CSUN, we have seen the effects of a pack mentality. Hazing claimed the life of Armando Villa because no one spoke up. It was normal to go along with a fraternity ritual. Someone could have saved his life.

And we can save the lives of sexual assault victims if we hold ourselves personally responsible for speaking up and taking action.

The problem is a collective one but if we are not strong individually, we will never be strong enough to overcome rape culture and break this cycle of abuse.

I want so much more than “Yes Means Yes.”