“How are we going to pay for our children’s college education?” That is a question that can paralyze any parent in America today.

When 18-year-old Jared Devon from Chapel Hill, N.C. decided in 2015 to apply for a bachelor’s program in international business at The Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, also known as the University of Leuven in Brussels, he was reluctant to apply for college in his hometown, but there was another, more important reason. “I wasn’t super interested in any of the options in North Carolina, and going out of state was way too expensive,” said Devon.

Devon heard about a website called Beyond The States, an international college advising service, “[They] help high school students find colleges abroad and [they] showed me a few schools, I applied here and got accepted, I visited, and I liked it a lot.” Devon had no idea how many Americans were studying abroad, and he didn’t know a single person from his hometown who had done so for more than just one semester. But then he came to Brussels, and met three other Americans in his class.

The exorbitant costs of college in the United States is what is leading more and more Americans to head east of the Atlantic in order to graduate debt-free. Europe is increasingly becoming the world’s top social hub, and Germany, Norway, Finland and Iceland are some of the countries that have started to offer free tuition at public colleges, and at some private universities, for international students. The classic semester abroad to experience a culture outside ones own has turned into a complete bachelor’s, and in some cases even master’s, degree. “Students can get an entire bachelor’s degree for the cost of just one year at some U.S. schools,” said Thomas Viemont, co-founder of Beyond The States.

Nationwide, student loan debt is currently at $1.3 trillion, and the number of American students with debt is currently 40 million, which is more than the entire population of Canada. In 2015, the average student loan debt was over $30,100, according to The Institute for College Access and Success (TICAS); this is a four percent increase from the average debt of 2014 graduates. Increasingly, people seem to be looking to Europe for a college degree. According to the Association of International Educators (NAFSA) the number of U.S. students studying abroad for some credit during the 2014-2015 academic year was 313,415, an increase of nearly three percent over the previous year, and a 2012 report by Open Doors showed that more than 46,500 were getting their degrees abroad. Students can also graduate faster. In Europe one can earn a bachelor’s degree in three years, as opposed to four, or in some cases even up to six, in the U.S. “Many programs are three years rather than four here, and that extra year is more cost savings and a year sooner in the workforce,” said Viemont.

Still, not all colleges in Europe are completely free for Americans. According to Bloomberg, European colleges want American applicants because they can charge higher tuition for non-EU residents. But as circa 98 colleges in Europe ask tuition of under $4,000 per year, Americans in Europe will still pay considerably less than they would at home. In a 2015 interview by the BBC soon after Germany announced free tuition for all, Berlin’s Secretary of Science Steffen Krach said schools not only allow, but want, foreign students to study for free, even with the costs falling on the taxpaying citizen, “It’s not unattractive for us when knowledge and know-how come to us from other countries and result in jobs when these students have a business idea and stay in Berlin to create their start-up,” he said. In relation, Viemont also points to the low birth rates in Europe, where the birth rate in central Europe is 9.9 per 1,000 people (compared to e.g. 38 per 1,000 people in sub-Saharan Africa), according to data by the World Bank. “The birthrates among the more affluent countries have declined significantly over the past decades, and as a result, there’s a shortage for talent. International students can fill those needs,” said Viemont.

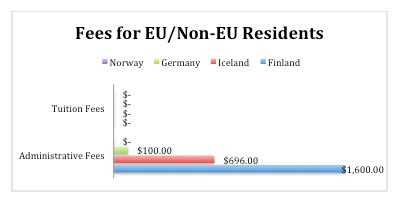

But does even “free” really mean free? According to a 2016/2017 national student fee report by the European Commission, though schools in countries like Germany, Iceland, Finland and Norway offer completely free tuition, there are other costs associated to take into consideration. Beyond visa fees, travel and living expenses, many schools charge administrative fees, and these vary from school to school. While schools in Germany charge fees under $100 per year, those studying in Iceland are liable to annual fees of at least $1,600.

Still, these are significantly low amounts compared to the U.S. where the average tuition cost of public colleges is $9,410 and $32,405 at private colleges, according to College Board. “My school costs less than $1,000 per year,“ said Devon. “I don’t have any regrets.”

However, one factor that keeps Americans from choosing to study outside the U.S. is the fear that a European degree will not hold as much weight as an American one. “It is questionable whether a European degree will be acknowledged by U.S. companies looking to hire, because they [may not] know it and don’t have any metrics to measure it,” said Nicholas Dungey, professor of political philosophy at California State University Northridge and Anglo-American University in Prague. “There is some sense in what a U.S. college degree is and what you had to do to get it, as opposed to a degree from a European school, [they] don’t know what to compare it with, [they] don’t know how to measure it.” Another potentially discouraging factor is the assumed language barrier. There is a common belief that by studying outside of the U.S. you will have to learn a new language, however Viemont says that the notion is false: “It is a myth or a misconception. We have assembled information on over 1,500 bachelors programs at more than 300 schools in non-Anglophone European countries,” he said. “These programs are conducted entirely in English. No foreign language is needed for admission and all of the classes and classwork will be in English.”

Overall the idea of graduating debt-free still seems to be worth the risk, and these minor bumps are insignificant to students like Anna Barr, who studies ecology and biodiversity at Stockholm University in Sweden. “I would have had regrets if I didn’t do it, it is scary but it was now or never,” said Barr. “I get a double experience, going to school but also experiencing a different culture.” As she recalls the reasons she decided to get her degree in Europe, she gently pets Werner, an adopted cat who came along from the U.S. “Having a little animal here made a huge difference,” she said. “My boyfriend and I just happened to see a movie by German director Werner Herzog before we got the cat. The adoption woman was a crazy cat lady, she was also German, and her accent reminded us of Herzog.”

Beside the natural desire for exploring a world outside one’s own, the college and university greed is the main thing that drives so many Americans to flee the country in order to avoid high student loans. According to CBS, there are over 320,000 waiters and over 100,000 janitors in the U.S. with bachelor’s degrees. This seems to be not only because of a shortage of available jobs for graduates, but also the inevitability of paying off the mountain of debt one has racked up to pay for a degree. A report by the Federal Bank of New York stated that tuition at colleges with many borrowers increased after federal student loan programs expanded. It raises the question whether student loan increases affect the costs of college? Or at the very least, it enables them? Between the years 1973 and 2012, federal student aid has increased by over 500 percent, and college prices have followed. Thus the pursuit of education has become a veritable catch-22, where students a forced to take out higher loans in order to pay higher tuitions, and schools are able to charge higher tuitions because students are allowed bigger loans. “Schools in the U.S. are for-profit institutions, corporations, they try to do the best they can for students while being, but function like corporations,” said Dungey.

The current education system in America is letting graduates drown in debt, circling in the wait for a long-overdue intervention. In the meantime the number of American students printing names of European universities on their resumes increases every year. “These students will gain tremendous perspective from living and studying with people from diverse backgrounds. They will become citizens of the world,” said Viemont. More importantly, they will graduate debt-free. “We believe more people should, and our own children will.”

When Devon found out he had been accepted to KU Leuven and was moving to Europe, the first thing he did was to Skype his sister, a teacher in his hometown. He donned a big smile and burst into laughter as he reminisced, “Yeah, my sister was so happy for me. Mostly because she can visit me here!”