As the plane halted to a stop on a grassy airstrip, dozens of children rushed over. To local boys and girls, the arrival of a plane indicated a special event, and passenger David Blumenkrantz shared the same sentiment, for it marked the first day of what would unknowingly be an eight-year stay.

From that moment, 29-year-old Blumenkrantz set foot in Manono — a town located in Zaire (present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo) — in January 1987, he began to document his first visit to Africa through photojournalism, specifically portraiture.

Blumenkrantz, hired by InterAid International, a U.S.-based non-governmental organization that operated relief and developmental efforts in numerous countries, assumed the role of information department coordinator in Nairobi, Kenya.

Although the opportunity to travel to Africa through InterAid International was unexpected, it was well-received by Blumenkrantz, who felt as though he had reached a standstill in his professional journalism career a year prior.

“In 1986, I was stuck in a dead-end job at a pop culture graphic arts lab in Hollywood, concerned that a journalism degree was being squandered, my interest in social justice consigned to hobby status,” said Blumenkrantz.

Arriving in Africa, Blumenkrantz took it upon himself to develop his own creative assignments based on self-interest.

“In the course of doing my assigned work I was able to do portraits,” said Blumenkrantz. As a result, thousands of photographs were taken from his arrival in 1987 to his departure in 1994, which would eventually become content for his book published 25 years later.

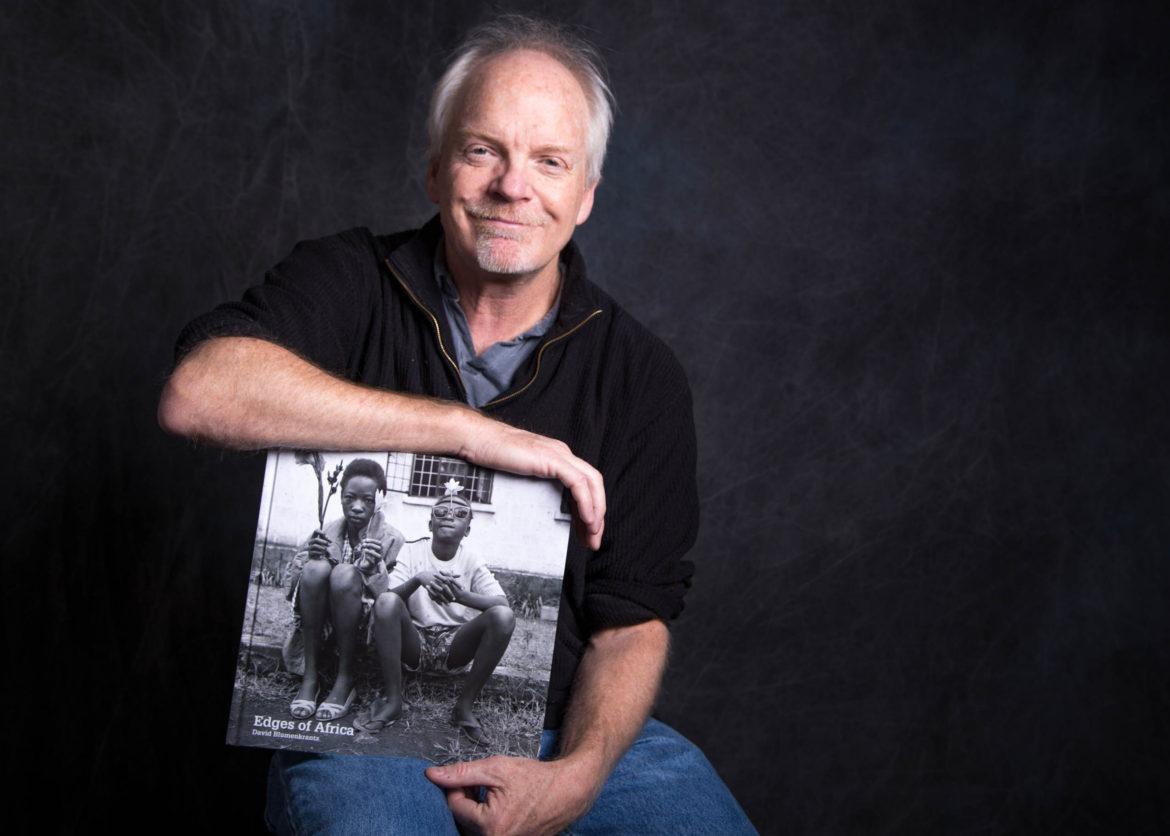

Over 200 “portraits, street photographs and journalistic images” were chosen to line the pages of Blumenkrantz’s self-published work, a 190-page photography book titled “Edges of Africa” that was officially released in December 2018.

“Putting it all in one volume was important to me,” said Blumenkrantz. “I wanted to have this body of work, eight years of work, put into a traditional book format. The difference between a book and anything else is that a book is tangible and different than looking at photographs on a screen.”

Portrait-style photography allowed Blumenkrantz to snapshot local individuals in a way that felt natural and comfortable for both parties involved.

“Portraits are not photographs, they’re people,” said Blumenkrantz. “And people are least threatened because it is implicit that it’s a collaboration.”

It was through this respectful photographic approach that permitted Blumenkrantz to gain trust from his subjects.

However, Blumenkrantz posed a threat in the eyes of skeptical and weary residents for being a white photojournalist. Extracted from a letter written to a relative in April 1988, Blumenkrantz shares recounts of such instances in his book:

“I was detained for questioning by the Nairobi police, accused of being a spy on more than one occasion, and had my deportation facilitated by a senior government official who was also an in-law and made no secret of his disdain for Americans,” wrote Blumenkrantz.

This commonly-adopted attitude partly inspired Blumenkrantz to title his book, “Edges of Africa.”

“Edges comes from the notion of no matter how long I stay there I’ll never be African,” said Blumenkrantz. “I’ll always be on the outside looking in.”

Nevertheless, Blumenkrantz was not discouraged from embracing his environment and assimilating to the surrounding cultures.

“From Mugumu (a town in Tanzania) to Uthiru (a settlement in Nairobi) I always felt welcome,” said Blumenkrantz. “Even when the cupboard was bare and their donkey’s ribs looked like a xylophone, there were smiles and laughter and good-natured kidding all around.”

To Blumenkrantz, the intimate connections he made with natives as well as his willingness to participate in African culture during his stay is illustrated in his work.

“What distinguishes this book from other photographic collections on Africa is the personal story — the unique experiences and misadventures of a Mzungu-American (Swahili for “white man”) navigating, living and working within but existing on the edges of a world he adopted as his own,” said Blumenkrantz.

For Blumenkrantz, respectfully embracing the culture meant checking his white privilege.

“Being smitten with all things African was not an unusual reaction for a mzungu, and I took it to some extreme,” said Blumenkrantz. “Having been raised basically lower-middle class, I readily identified with people whose lives seemed a noble struggle.”

The relationships and friendships Blumenkrantz formed during his time in Africa temporarily led him to believe that he would permanently relocate there.

“There was a time when I thought that I would never want or need to leave Africa, but gradually that changed,” said Blumenkrantz. “Romantic idealism was gradually being replaced by a more practical human interest and respect, and a healthy skepticism about my actual position in life.”

In October 1994, eight years after his initial arrival in Africa, Blumenkrantz found himself saying goodbye.

“It all ended much differently than it had begun some eight years earlier,” said Blumenkrantz. “My heart was in my throat while being escorted to the airport in a government Mercedes, with the same man who had put the wheels of my attempted deportation in motion two years earlier.”

This time around there were no curious children present to send Blumenkrantz off in the same welcoming fashion in which they had received him. The moment of departure had come at last.