Students organizing against CSUN’s implementation of Executive Orders 1100-R and 1110 appeared in front of the Oviatt Library Thursday afternoon while the first Faculty Senate meeting of the spring 2019 semester was held inside.

Students held a “teach-in,” where they presented a timeline of disenfranchisement by administration over the course of the implementation of these executive orders.

Rocio Rivera, a double major in Chicano/a studies and sociology, opened the teach-in by explaining the executive orders and running down a list of grievances the students and faculty had with CSUN administrators.

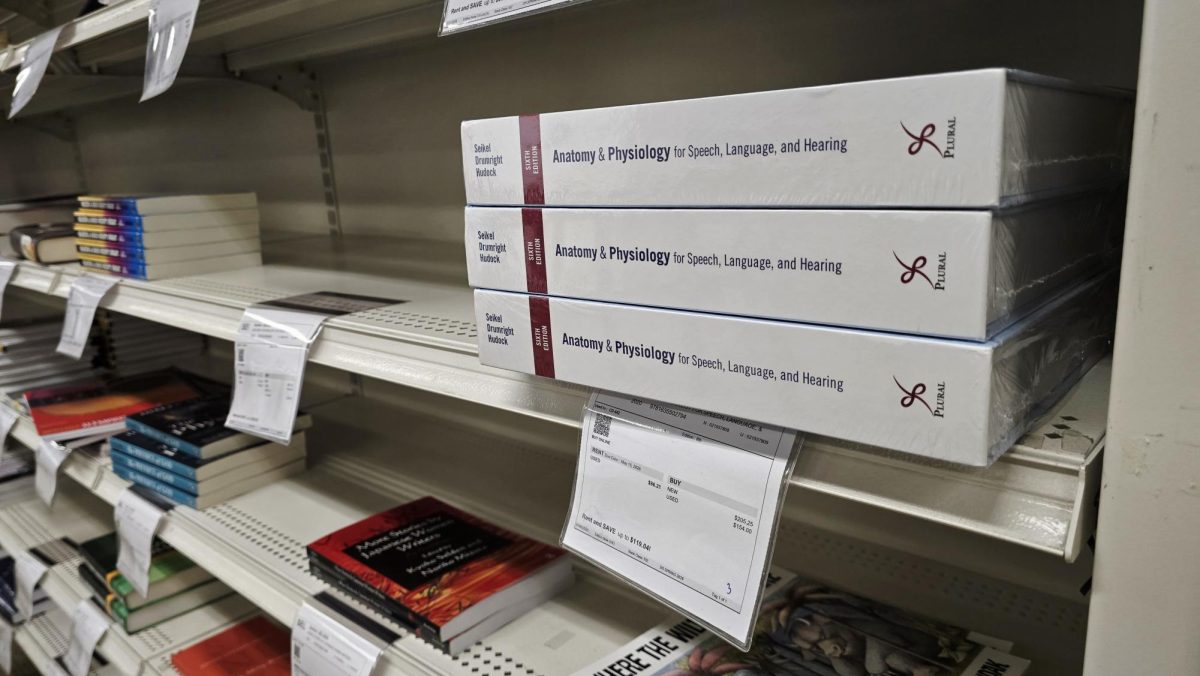

These concerns included changes to curriculum like the cancellation of Chicano/a studies department courses, the elimination of developmental math courses and changes to writing courses that negatively impact students of color.

“So basically these executive orders are fucked up,” Rivera said. “And they’re going to affect our students of color, they’re going to affect our working class students because they’re basically trying to make the entire Cal State system … very uniform.”

Rivera also made a point to mention that inside the library, CSUN’s first Faculty Senate meeting of the semester was underway, calling into question how student attendance for the meeting was being managed, echoing the concerns of protesters in the 1960s who questioned the validity of closed Faculty Senate meetings.

“Ever since students started mobilizing last year, students have to go through the system and get selected to actually go inside the Faculty Senate meeting,” Rivera said. “That is not done at any other Cal State.”

Rivera finished by calling on that history, warning that these executive orders would hinder ethnic studies at CSUN in their entirety.

“Our ethnic studies departments were actually founded on taking over the university here in Bayramian Hall,” said Rivera, speaking to the surrounding crowd. “1100-R is going to dilute those departments.”

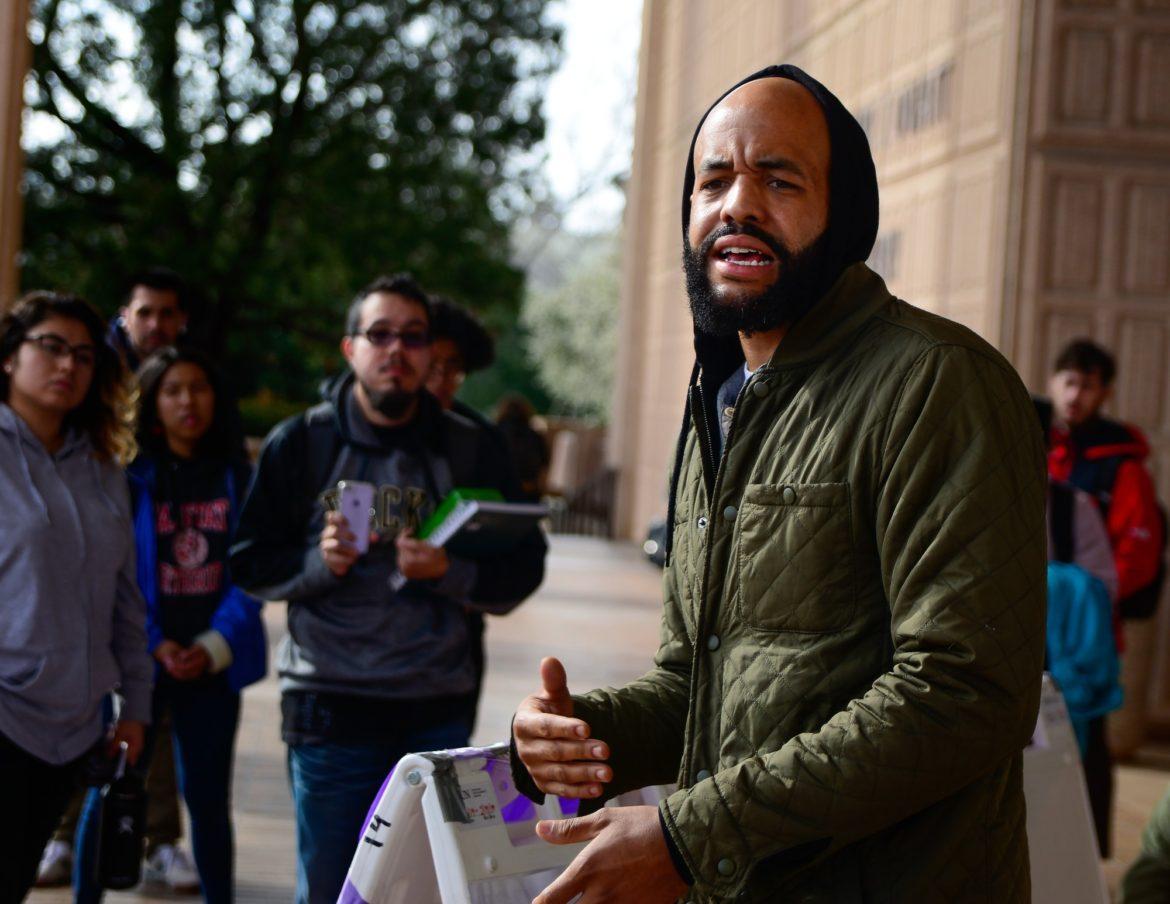

Diego Paniagua, a 26-year-old graduate student in Chicano/a studies and an organizer with the student movement, said this two-year movement has been hard on students.

“At this point, the angle that we’re taking is to just to continue to educate,” Paniagua said. “It’s beyond taxing that the students have been having to be the educators in this movement … be forced to operate with patience after being painted as unruly or uneducated.”

Paniagua said that administrators who lobby so hard for these executive orders claim they’re based in data, but the students have seen nothing to back that up.

“We’ve been saying, ‘Well where’s the data that says that it’s right?’” Paniagua said. “And they’re like, ‘We don’t have the data and we’re not gonna provide it.’”

Paniagua said their goal for this event was to spread awareness of a lessening quality of education because of these changes.

“Just really highlighting the negative impact that it’s already doing to departments now just so Stella (Theodoulou) can know, ‘You are responsible for this amount of students dropping out and you are responsible for these classes being cancelled,’” Paniagua said.

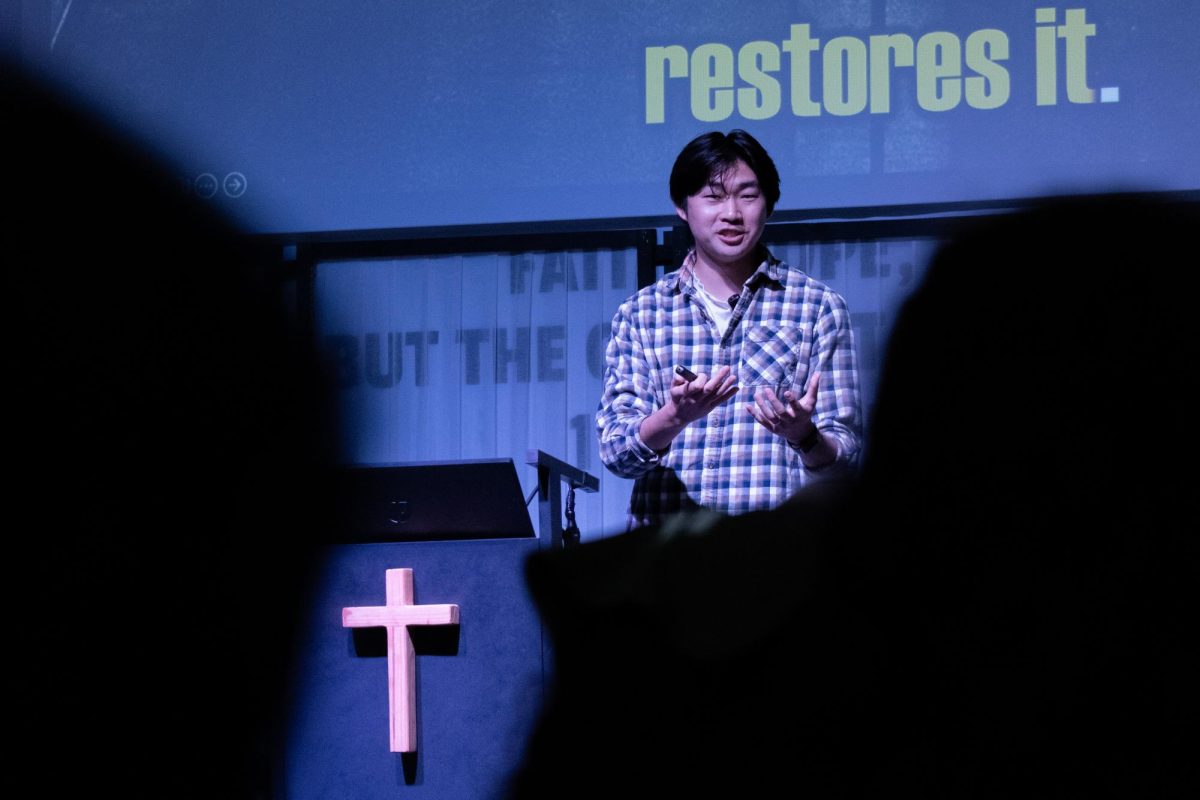

Justin Marks, a 30-year-old Africana studies major, got up to speak about how students can band together to support each other in crisis instead of calling 911, spurned by his reaction to the shooting threats from the fall 2018 semester.

“It made me think what if, what if something happened, do I feel safe?” Marks said. “But what I saw when I came to campus was more police than I had ever seen before … All of my classes are in Sierra Hall. The graffiti that was threatening blacks and Jews was in Sierra Hall. So, for me, the response that it would just be security cameras and police on campus, to increase the amount of guns increases my likelihood of being shot, right?”

Marks said it was important that these conversations were held between students in order to have a game plan for when both an active shooter and the police are threats to students of color.

“How can I call myself an abolitionist and at the same time fault the police for not protecting me?” Marks said.

After his speech, Marks made his own remarks on EO 1100-R and 1110, saying that without ethnic studies on campus, cycles of violence will repeat.

“For me it is also a matter of life and death when we talk about the executive orders and ethnic studies,” Marks said. “It’s the type of education that we get in ethnic studies courses that I think can make the difference.”

Towards the end of the teach-in, 19-year-old Fernando Lopez-Gonzalez led a speech on white supremacy at CSUN.

Lopez-Gonzalez cited an earlier Faculty Senate meeting where students were prevented from entering the meeting at the same location as faculty and that Mary-Pat Stein, the Faculty Senate president, had previously told the Chicano/a studies department chair, Gabriel Gutiérrez, to “Speak proper English.”

“For those people that do not believe that white supremacy doesn’t live on campus,” Lopez-Gonzalez began. “We have multiple incidents, not just the swastika,” referencing again the graffiti that appeared in Sierra Hall in fall of 2018.

Paniagua, who stood nearby while each speaker took their turn, said before the event that the core of the fight is really about holding the administration accountable.

“They’re trying to paint themselves as them being in the right and they’re doing this for the benefit of future success and getting students out of here faster … but at what expense?” Paniagua said. “And it’s turning out it’s at the expense of the ethnic studies departments, the gender and women’s department (and the) queer studies department.”