This year marks the 50th anniversary for Chicana/o studies, and this week the 50th anniversary of EOP at CSUN. We’ve decided to show our readers the faces behind these powerhouse organizations, from students whose lives were changed by EOP to professors fighting for ethnic studies. Their stories show us why it’s important to have these entities on campus.

Martha Escobar, Associate Professor, Chicana/o Studies

Martha Escobar was walking around UC Riverside’s campus her freshman year when she came across a center called “Chicano Studies Program.”

“I didn’t know what it was, I didn’t know what Chicano meant, but I knew it was speaking to me,” said Escobar.

She walked in and the assistant director immediately welcomed her to the space, encouraging her to sign up for student organizations. She signed up for MEChA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicanx de Atzlán), took courses in ethnic studies and eventually became involved in the fight for ethnic studies.

During her undergrad she and other student organizers fought against the implementation of another program that would threaten to take away resources from the ethnic studies department. She could not allow the space she connected with to be taken away.

“That’s where I found a home, somewhere where I belonged,” she said.

Fast forward to 2010-2011, when Escobar was in the job market looking to become a professor. She had three interviews lined up with different schools, including CSUN. During her first interview at CSUN she met the faculty and students and immediately felt a connection to the space.

Before even interviewing with the other universities, she called to say she had chosen CSUN. Her adviser told her, “Martha, this is not how this works.”

“You don’t understand, I feel at home,” said Escobar.

Escobar has become a face for ethnic studies and other social justice programs. She fights for the budget and allocation of different resources on campus, such as Social Discourse and Exchange, a program that brings faculty together from different departments to teach students how to advocate for social justice issues. She does it all for the students.

“For me the most rewarding part is working with the students and seeing that, okay, I am not crazy, this stuff matters to them and they’re actually taking action to create those changes that I think are necessary for the world to become more livable,” she said.

Escobar wants other future educators in ethnic studies to know that it will be a constant fight for students, to never lose sight that their work has meaning and that they can change students’ lives.

For her students that have been fighting for ethnic studies, she thanks them for all the work they have done and reminds them of the bigger picture.

“I hope that they stay grounded on why they do what they do, what’s their life purpose, and why are we doing what we are doing,” she said.

Gina Masequesmay, Department Adviser and Professor of Asian American Studies

Gina Masequesmay points to all the signs in her office that read “I am LGBTQ, I am a first-generation student, I am a student of color.”

“See that list, I’m all those things!” she said proudly.

For her, identifying with those factors helps her advocate for her students. Holding back tears, Masequesmay shared how her mother was harassed at work and how she didn’t know she had the right to file grievances against discrimination and harassment. She says because of that she relates more to her students that are always struggling.

That’s why she believes that ethnic studies provides a sense of belonging to students on campus.

“There’s more than doing well in school, you have to feel safe,” she said. “If you feel like your social environment is accepting of you then it’s easier to try to do well instead of always fighting and looking around, being afraid of who’s going to attack you next.”

The first time she took an Asian American studies class at Pomona College as an undergrad, she could finally claim herself as American with rights and no longer just an immigrant.

Masequesmay sees ethnic studies as a way to challenge the dominant perspectives and other issues. As she became involved in the fight for ethnic studies at CSUN, she noticed the administration’s efforts to redefine student success by pushing a four-year graduation rate and other factors. She and other faculty members know that many students can’t do that because of their situation, but administrators don’t seem to realize this.

“They want to enforce this one-size-fits-all policy that comes from the Chancellor’s Office,” she said.

Masequesmay explains that it’s important for students to be liberal in their education process, because that’s how they learn about themselves.

“The process of learning is more than a formal education,” she said. “In learning sometimes, you meander, you don’t go in a straight line. But in that meandering you’re learning something about yourself, what you like what you don’t like, what excites you.”

In response to the recent executive orders, Masequesmay says that she won’t give up.

“We’re not gonna give up, as people of color, as faculty that chooses to be at an institution that serves students of color,” she said. “We chose to be here because these are the population of students we want to work with. We’ll say no. We’re gonna try to resist it.”

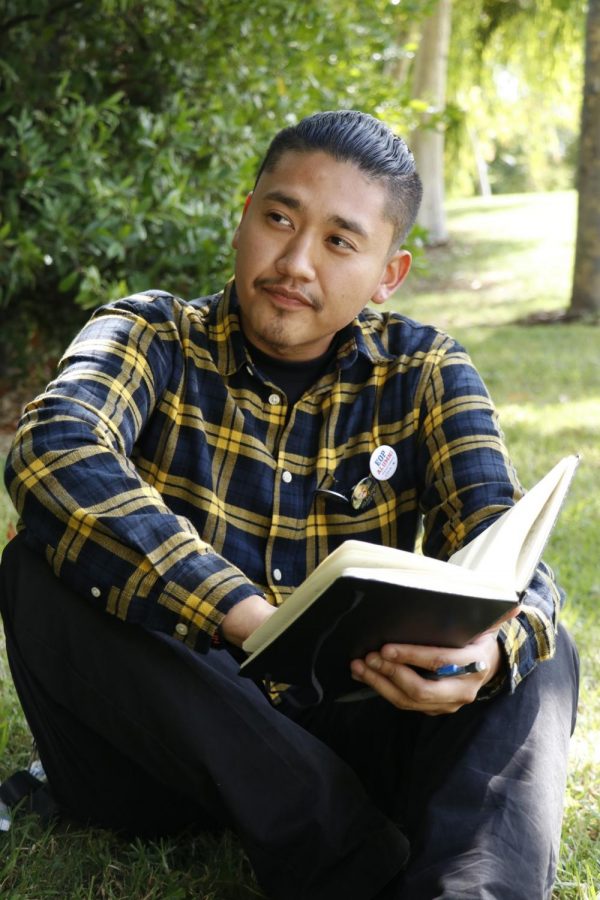

David “Chino” Contreras, Graduate Student, Social Work

CSUN graduate student David “Chino” Contreras says that EOP provides more than just academic support — it gives students a second chance in life.

EOP serves historically low-income, educationally disadvantaged and first generation students. Chino says college students already face challenging circumstances on a daily basis. There isn’t enough time to process it when it comes to school.

“When we get here we have to handle business,” he said.

Chino says it’s rare for an institution like CSUN to provide an environment like EOP because it is not designed to serve people of color.

“This institution is not built for us to survive, but yet we are here. It doesn’t give us time to feel the pain, to feel the love, to feel the gratitude,” said Chino.

He reflects back on when former EOP Director Jose Luis Vargas gave Chino a safe space. Both of them sat down across from each other when Vargas, known for his calm personality and voice, asked Chino, “How you doing, mijo?”

Nobody had ever spoken to him in that manner, and he was not used to someone giving him attention and talking to him. Even reminiscing on this memory was difficult for him.

Even after Vargas passed away in March of 2016, Chino and other EOP students continue to see Vargas as a mentor and father figure.

“For Jose Luis to come and take in every single each one of us individually and talk to us like we’re basically his sons or his daughters,” Chino said, explaining that he had no one to look up to growing up.

Back in Pacoima where he grew up, Chino explained that nobody had time for him. He was raised in a “gang-infested community, (with) a lot of drugs and violence. A lot of pain and trauma I grew up watching since I was nine years old.”

Chino began to heal after Vargas told him to embrace his emotions. That is why he decided to get his master’s in social work at CSUN, and he’ll be graduating this spring.

Chino says the love, the family that EOP has built, is rare. If it wasn’t for EOP, Chino would not have been an artist, poet, activist and everything he learned from his communities.

“The people I surround myself with, EOP is one of them, communities that help create me,” he said.

Anthony Cunningham, Third Year, Recreation and Tourism Management

Photo courtesy of Anthony Cunningham.

Loud, energetic and enthusiastic is how Anthony Cunningham describes himself. EOP changed his mindset, but not his personality.

“(It) changed the way I looked at the world, changed the way I looked at a different situation, the way that I look at my story,” he said. Cunningham moved from city to city at a young age, from Inglewood, to East LA, to Compton, to Watts and to the Antelope Valley.

He’d been in the foster care system since he was born, up until college. He jumped from one home to another and had difficulties making friends at school.

“I didn’t know if I was going to stay at that place for a long time. I never really knew what my time limit was,” he said.

He’s now in college for the long run. Cunningham is in his third year majoring in recreation and tourism management. “It’s too late to back down, I’m too deep in it,” he said.

EOP is the backbone of his academic journey. EOP Resilient Scholars supports former foster youth academically and personally, providing them resources such as financial aid, academic advising and student housing.

If it wasn’t for them, Cunningham would not have a seat in education. He’s able to be in an environment to share his struggles.

“I have a community here with my EOP people that understand the struggle. They’ve been through some form of foster care or guardianship, so they know the struggle,” said Cunningham.

He points to Gina Gonzalez, the coordinator of the Resilient Scholars Program and associate director of EOP, as an important mentor during his time at CSUN.

“Gina is my mother, my school mom, she is always there when I need her whether it’s for academics or personally,” Cunningham said.

He recalls a challenging moment when Gonzalez saved him from being homeless. He had difficulty finding a place to stay during the summer in Northridge while taking his final exams.

“It’s super difficult for foster youth who come to a four-year university, it’s difficult finding housing over the summer,” he said. “Foster youth don’t have family to go back to during the summer.”

Despite the obstacles, he continues to thrive.

“Live your life to the fullest, live everyday like it’s you’re last,” Cunningham said. “Be creative and stay 10 toes down.”