American Indian Studies Association hosts Indigenous Peoples’ Day celebration via Zoom

The American Indian studies program, American Indian Student Association and Fernando Tataviam Band of Mission Indians hosted a Zoom meeting for Indigenous Peoples Day on Mon. Oct, 12, 2020.

October 12, 2020

For Indigenous Peoples’ Day, CSUN students and faculty, the CSUN American Indian studies association program and the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, shared the history, language and sovereignty of the Indigenous people of the San Fernando Valley, on Monday via Zoom.

Indigenous Peoples’ Day is a new holiday that started as a counter-celebration of the controversial federal holiday, Columbus Day. In Los Angeles County, Indigenous Peoples’ Day has replaced Columbus Day for three years.

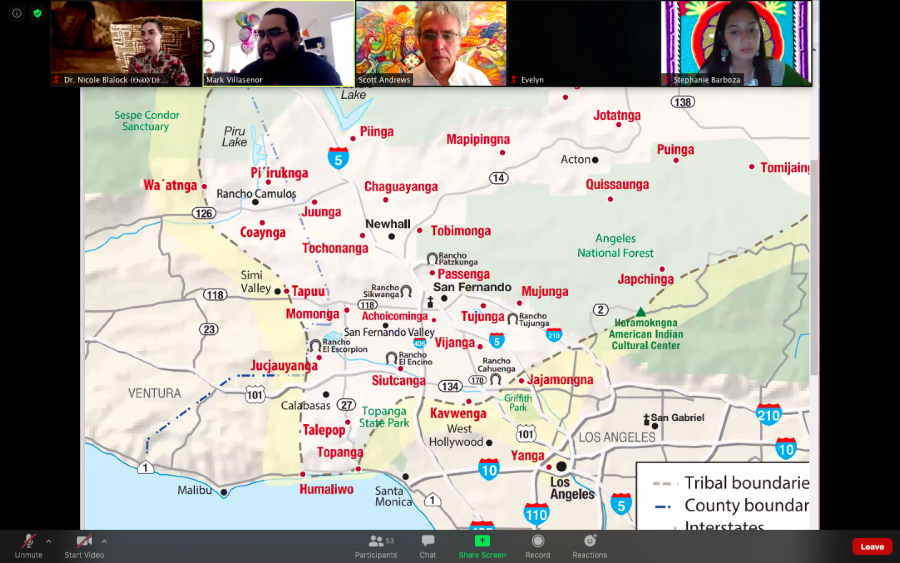

The meeting started off with CSUN alumnus Mark Villaseñor and Professor Scott Andrews, the interim director of the American Indian studies program, giving a history lesson on how the San Fernando Valley looked and the importance of land acknowledgement to roughly 50 participants.

“Land acknowledgment is an increasingly frequent event for major institutions, but especially for universities who make acknowledgement of the land that they sit on and who their original occupants were and who their current owners are,” Andrews said. “There’s different ways that land has been stolen or erased or taken away, so it’s an acknowledgment of those owners and the acknowledgments that we as a university are kind of uninvited guests on the land in certain ways.”

Andrews said they proposed ideas to President Dianne F. Harrison’s office, such as acknowledging the land and creating more indigenous plant zones on campus.

In Harrison’s welcome address this year, she opened her speech with a new tradition — acknowledging the Sesevenga land that CSUN is built on.

Villaseñor, the vice president of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, said it’s important to acknowledge the older generation and continue the culture they have started.

“We have a big reverence for the people that came before us,” Villaseñor said. “We recognize as a cultural aspect that we stand on the shoulders of giants. We build on the generation before us, that is the whole purpose in our culture. We respect those who came before us, our elders, their parents and all these things, because one day you are going to be that elder who imparts the knowledge to the next generation.”

The Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians is currently in the process of attaining federal recognition. The Indigenous nation has a rich history dating back to 450 C.E., according to their website, which shows Indigenous people as the first inhabitants of the Simi Valley, San Fernando Valley, Santa Clarita Valley and Antelope Valley.

To get a clearer picture, Andrews shared a map of the San Fernando Valley which showed the tribal boundaries in the San Fernando Valley such as Passenga, Tujunga, Achoicominga and Siutcanga.

“You hear these names: Tujunga, Topanga, Rancho Cucamonga. You hear these names and you don’t realize what they are, because that’s what has been given to us in history,” Villaseñor said. “That’s the importance of knowing whose land are you on.”

The #IndigenousPeoplesDay hashtag was trending on Twitter on Monday and Stephanie Barboza, co-chair of AISA, said social media can be helpful in educating a wider audience.

“It has helped us get more people involved and let more people know about the lands that CSUN is on and how we can support the Fernandeño Tataviam beyond land acknowledgements and talking about ideas of how the university can do better,” Barboza said.

Nicole Blalock, an assistant professor with the American Indian studies program, explained that the Indigenous community is based on intentionality, relationality and kinship.

She described the definition of Indigenous as a diagram of concentric circles — from a broader global and western hemispheric scope, down to the experiences of American Indians and California Indians.

“It is a big complicated issue but in this space at least, we are all relations and we are all kin and we are working together to lift up each other’s voices and experiences,” Blalock said.

Editor’s note: The story was updated at 12:06 p.m. on Oct. 13 for clarification.