Some might call him a dead man walking, or even a ghost. If things had gone as planned for the state of Florida, Juan Roberto Melendez would most certainly be dead.

Melendez spent 17 years, eight months and one day on Florida’s death row for a crime he didn’t commit.

“It was hell and I wanted to get out of there,” Melendez said.

He lived in a 6-by-9 cell infested with rats and roaches. Melendez would often have fleeting thoughts of suicide, but never succumbed.

“Every time I wanted to commit suicide, our creator, God, would send me an awesome dream, a dream of happier times, a dream of my childhood, a dream of hope — hope that one day I would be free,” he said.

On May 2, 1984, Melendez was arrested by the FBI for the 1983 murder of Delbert Baker, a man Melendez claimed he had never met. Even though Melendez was scared, he thought that everything was just a mistake and he would soon go back to his life as a migrant farmer.

But it took the Florida court one week to sentence Melendez to death for first-degree murder and armed robbery. During his interrogation and trial, Melendez never received an interpreter.

At the time, he only spoke Spanish and could neither read nor write in English.

“I was naïve to the language and I was naïve to the law,” Melendez said.

In 2002, Melendez was exonerated from Florida’s death row after a taped confession by the real killer was discovered. After three appeals, more than 13 attorneys and faith, Melendez was finally a free man.

Upon his release, he received $100 compensation from the state of Florida for transportation and food. Florida’s ‘Victims of Wrongful Incarceration Act’ states that wrongfully incarcerated people are not eligible for compensation if the defendant had a prior record, which Melendez had.

But Melendez’ story is not unique.

A 2012 report by Death Penalty Information Center said 141 death row inmates nationwide have been exonerated since 1973. In California, three people have proven their innocence.

“We can always release an innocent man from prison, but we can never release an innocent man from the grave,” Melendez said.

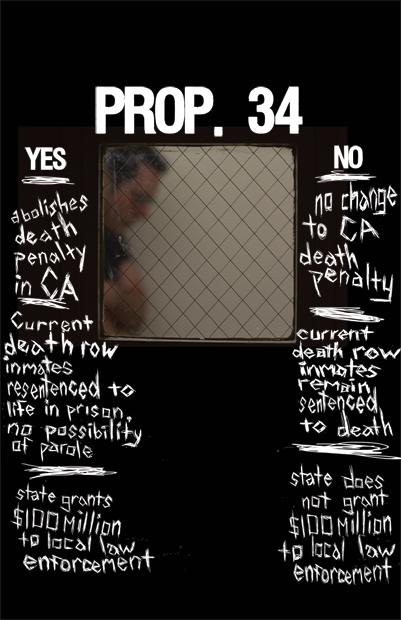

In November, California voters will be asked if they want to abolish the death penalty, which currently affects 724 inmates — the highest in the nation.

If voters say yes to Proposition 34, the initiative will abolish capital punishment and impose a new sentence of life in prison without the possibility of parole for previously condemned inmates.

Opponents of Proposition 34 say Californians should not throw away a useful tool, but should fix and improve the death penalty. They believe that the state should modify and limit the time for filings certain types of appeals and house death row inmates in other prisoners.

Jonny Bridge, a sociology major at CSUN, attended one of Melendez’ lectures when he shared his story. After the lecture, Bridge changed his view of the death penalty.

“Unless there is 100 percent DNA evidence, there shouldn’t be death penalty,” Bridge said.

Bridge still believes that the death penalty should exist, but said California needs to either redraft their system or abolish it.

However, supporters of the measure argue that the death penalty is not only broken, but it is also expensive.

In 2011, a judge and Loyola Law School professor conducted research showing that California taxpayers spend more than $170 million per year confining death row inmates—the costliest death penalty system in the country — compared to inmates that serve life without possibility of parole.

But as the research illustrates, the tax money has not been financing the execution itself.

Only 13 death row prisoners have been executed since 1978 in California. But while the state has spent $4 billion trying to enforce capital punishment, $3 billion has been spent on trial costs and petitions.

Proposition 34 would also reinvest $100 million that will be saved from abolishing the death penalty to fund law enforcement agencies and require inmates to work while in prison so their wages can be applied to any victim restitution fines.

Kevin Riggs, spokesman for the No on 34 campaign, said that the cost-saving numbers for abolishing death penalty are greatly exaggerated and biased.

“They are going to have continuing court costs no matter what kind of case it is,” Riggs said. “Because the judge and lawyers are still going to the courthouse whether it is a death penalty or not.”

But it is not only the cost of the death penalty that is raising questions — eliminating it could save $183 million for Californians.

Some also argue that death row prisoners are receiving two distinct punishments: the death sentence and years living in conditions equivalent to solitary confinement.

From 1978 until 2011, more than 78 death row inmates have died of natural causes or by suicide in California.The long wait for execution, which in this state can take more than 20 years, inspires some inmates to take their own life.

“You might be dead, but you will be free,” Melendez said, who had friends that committed suicide.

Opponents of Proposition 34 also believe that the death penalty gives family of the victims a sense of justice.

Melanie Shaw, 21, an English major at CSUN, said she supports the death penalty because of the “eye for an eye” concept.

“You took away all possibilities for that person to have a life so why should you deserve to live,” Shaw said.

But Karren Baird-Olson, a sociology professor at CSUN, disagrees. In spite of her 3-year-old granddaughter being murdered in 1985, Baird-Olson says that the “eye for an eye” concept eventually makes us all blind.

“Killing somebody doesn’t bring back the person you lost,” Baird-Olson said.

Baird-Olson said that revenge and retribution are not qualities a civilized society should advocate.

“Why should I want the defendants’ family to go through what I went through,” Baird-Olson said.

Carl Adams, president of the California District Attorneys Association, said people should not oppose Proposition 34 for philosophical or moral reason.

“The existence of death penalty is a political factor that keeps the public safe and deters crime,” Adams said.

However, a 2011 report by the U.S. Census Bureau shows that the murder rate is usually higher in states with the death penalty compared to states without it.

In 2009, California’s murder rate was 5.9 per 100,000 populations. This was more than two times higher than Vermont—a state without death penalty—that had 1.3-per-100,000 populations.

But Melendez said that death penalty should not only be abolished because of deterrence or the cost of maintaining it, but also because it is a cruel system that legitimizes killing of another human being.

“The United States is the only country in the Western industrialized world that has the death penalty,” said Melendez. “California has an opportunity now to be on right side of history.”