Congress recently approved a plan that will amend the federal student loan interest rates from a fixed percentage to a rate that fluctuates with the market.

The approved plan, the Bipartisan Student Loan Certainty Act of 2013, took effect on July 1. This came after Congress failed to reach an agreement to extend the 3.4 percent interest rate previously instated. As a result, the rates doubled from 3.4 to 6.8 percent before the new bipartisan deal was approved.

The compromised deal will change the way federal student loans have worked in the past. For those who took out loans on or after July 1, 2013, there will be a fixed 3.86 percent interest rate for life. Students who take out loans during the 2015 academic year are facing an interest rate that will vary depending on the current market and be reassessed every 10 years.

Sophia Zaman, the president of the United States Student Association, said new legislation does not benefit students as much as it benefits the government.

“We had a lot of concerns about the deal. We feel like it is a little bit of a bait and switch,” Zaman said. “We felt like the 3.4 percent [interest rates] should have been extended.”

Despite fluctuating interest rates with the new bill, they will not exceed 8.25 percent for undergraduate loans and 9.5 percent for graduate loans.

In a press letter, California State Senator Barbara Boxer said the temporary lower interest rate for this school year is essential.

“If we do not have a cap on student loan interest rates, we are facing a real problem in the future,” Boxer said. “I have read stories of young people who were putting off marriage and having families because of the crush of student loan debt.”

This bill only applies to federal student loans such as the subsidized, unsubsidized and parent PLUS loans. Subsidized stafford loans are only available to students in financial need, while unsubsidized loans are available to all students. PLUS loans are available for parents of students.

CSUN student Alana Gallardo, a deaf studies major, has three semesters left before she graduates and is relieved that the new bill has passed.

“The temporary lower interest rate works great for me because I will be finished with school before the rates go up again,” Gallardo said.

However, Gallardo also said that the change in federal student loans will have a negative impact on students graduating after her.

“If the interest rates go up too high, students will never be able to pay off their debt,” Gallardo said.

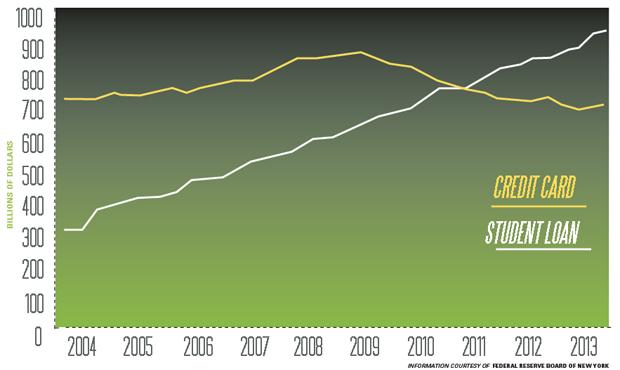

In 2003, the national student loan debt was close to $250 billion. In the last 10 years, this number has increased to nearly $1 trillion.

According to a 2013 report by the Federal Reserve, the national student loan debt is the second largest debt in the nation, surpassing both credit card and auto loan debt.

Shirley Svorny, CSUN economics professor, said the real issue is the accessibility of loans and grants, which will hinder students in the long run.

“Excess spending [in college] occurs because the pressure to limit spending is not there and so many students get financial aid and wealthier students’ parents just pay the bill,” Svorny said.

The average cost per year for a four-year college has increased from about $16,000 in 2000 to $21,000 in 2010. Meanwhile, enrollment has increased by nearly 40 percent between 2000 and 2010, from 15.3 million to 21 million.

More than 60 percent of students take out loans annually to pay for college. The American Student Association lists the current student loan statistics, showing that nearly 14 percent of graduates default on their loans within three years of graduating.

Professor Svorny predicts a possible drop in enrollment due to the interest rate change.

“Market interest rates force borrowers to consider what it really costs. People don’t spend money on things that are not very valuable,” Svorny said. “A college education is not valuable to many students because their interests are elsewhere, but the low cost draws them in for a few years before they drop out, sadly wasting their own money and the government’s.”