Cal State Northridge student Malek al-Marayati was in fourth grade on Sept. 11, 2001.

He remembers the day filled with chaos.

“It was all pretty abstract to me at the time just because I wasn’t able to understand it completely,” he said.

He especially remembers his father, Al Salam al-Marayati, current president of the Los Angeles-based Muslim Public Affairs Council, worrying that, as word spread that the attacks on Washington, D.C., and New York City were the work of radical Muslims, Muslim-Americans would “be demonized,” he said.

The younger al-Marayati described the days following the initial attacks.

“The transition period was so gradual between life before and after 9/11. It was such a momentous point of time for the Muslim-American identity, especially,” he said.

Al-Marayati, 21, a senior marine biology major and president of CSUN’s Muslim Student Association, remembers seeing footage of the attacks everywhere.

“I got to witness what everybody else was witnessing,” he said. “But I could not comprehend it completely until later on in my life.”

He remembers the stereotype of the Muslim terrorist flourishing in the weeks and months following the attacks. The attacks, al-Marayat heard at the time, were thought by Americans to be part of the “hidden agenda of Muslims around the world.”

Al-Marayat would experience the Muslim terrorist stereotype firsthand when he and his family were detained at the airport after disembarking from their return flight to the United States following a family vacation to Cancun about two years after the 9/11 attacks.

The authorities, al-Marayati said, never gave a reason for the detainment.

“My mom was freaking out,” al-Marayati recalls. “They had us detained for three hours.”

His family would be detained yet again several years later.

“That was probably one of the most dehumanizing things to be a part of,” al-Marayati said. “That was really an emotional part of my life when it happened.”

Although al-Marayati did not directly experience the demonization, racism and hate crimes some Muslims were subjected to at the time, he remembers learning about those acts through conversations with friends. Stories circulated among them about Muslim women who were given nervous glances when they ventured outdoors wearing the traditional hijab head covering.

Most of the rhetoric al-Marayati heard against Muslims in 2001 centered around television news broadcasts that used words such as jihadist and Islam in the same breath, although in reality, al-Marayati said, people did not buy much into that rhetoric, especially in Los Angeles.

He is grateful for that.

Past CSUN Muslim American Assn. President Mayid Charif, 21, claims Arabic and Syrian roots. His grandfather is from Damascus, Syria. Born in Colombia, Charif is a recent convert to Islam from Catholicism.

As a boy, Charif immediately understood the impact the attacks had on the world. It was something that nobody should come across, he said.

“I pray for the people who were killed,” Charif said. “I also pray for the people who committed this atrocity, for them to be guided to the right path.”

His family formerly resided in the Syrian capital of Damascus — aunts and uncles, mostly. Because of their Colombian nationality, however, Charif’s family was able to exit the country, although countless other families remain, unable to leave.

The dynamics of the Syrian crisis and war against terror in Afghanistan differ, Charif said, but the Syrian crisis nevertheless echoes the uncertainty the United States went through as it stood on the precipice of war with a foreign terrorist enemy in 2001.

“The United States is actually more isolated than they were before they declared the way against the Taliban, or before they invaded Iraq,” Charif said of the possibility of military intervention by the U.S. in Syria. “The United States is acting on its own. Even Britain, and now France, backed out.”

Twelve years after 9/11, al-Marayati said, the demonization of and stereotypes against Muslims have waned, although some instances of Islamophobia still exist. People no longer see Muslims as terrorists but as human beings. The attacks were carried out by a group of Muslims who committed terrorism in the name of Islam, but even other Muslims don’t consider the terrorists true adherents of the faith, al-Marayat said.

“They are not considered Muslims by other Muslims around the world,” al-Marayat said. “There are extremists in every religion who commit crimes against humanity, but that doesn’t mean that their religion is to be blamed.”

As president of the Muslim Student Assn., al-Marayat said it is important that people educate themselves about faiths they do not understand. His organization strives to inform people about what Islam is and is not.

“After the 9/11 attacks, people actually begin to inquire more about what Islam is,” Charif said.

According to Charif, conversion to Islam quadrupled because people began to look into Islam and discovered that the terms Islam, at its root, means peace.

“There are still a lot of people in America who still haven’t been convinced, who are still ignorant to what the truth is,” al-Marayat said. “There is still a lot of work to be done.”

A campus reacts

Archived Daily Sundial newspapers from the Wednesday, Sept. 12, 2001, issue describe a subdued, frightened, shocked, and mourning campus. Classes came to a halt as students listened to the former President George W. Bush, speaking from Booker Elementary School in Florida, declaring to the nation that a terrorist attack had been committed against the United States earlier that morning.

The Wednesday issue contrasted sharply with the issue published one day earlier, which featured Monday reports of heavy rain affecting the campus, conclusion of construction to rebuild the campus after the Northridge Earthquake, the end of the women’s volleyball team’s five-game winning streak, and an op-ed piece encouraging students to ride their bikes to school.

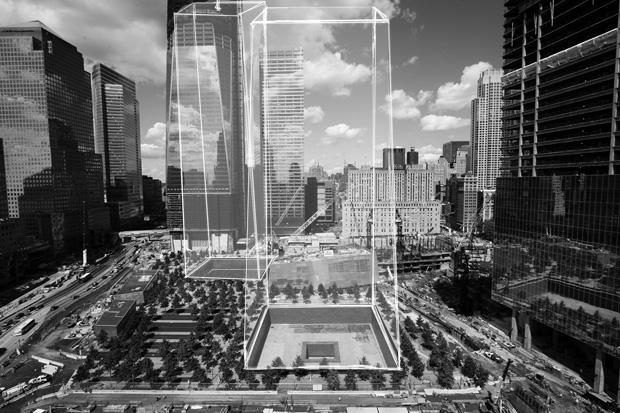

“The last vestiges of America’s innocence was stripped away from it as the Pentagon and the World Trade Center lay smoking in ruin,” read an op-ed piece written and published by the Daily Sundial staff in the Wednesday paper.

CSUN professor of music therapy and music department Chair Ronald M. Borczon was on campus the day of the attack. Borczon and a group of students organized a 60-strong community drum circle on the lawn of Cypress Hall. The name of each Californian killed as a result of the attacks, were given their own unique beat. Each of his students received the name of a victim, and they were encouraged to find out more about them.

“In essence, the rhythm of their name was given life through the beat,” Borczon said.

Borczon designed a beat for Melissa Rose Barnes, a 27-year-old U.S. Navy second class yeoman killed when American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon.

Borczon still remembers Barnes’s beat: “Melissa Rose Barnes, Melissa Rose Barnes — pa-pa-pa, pum-pum.”

“We just kind of unified everybody and given everyone a chance to be together and express their sadness and sense of camaraderie,” Borczon said. “Music can take the emotion and put it out.”

Over time, and as images of the attacks began to fade from constant rotation on television, life on campus returned to normal.

As a psychologist in University Counseling Services, Dr. Mark Stevens encourages people living in a time of crisis to continue following their normal routine and share their story. Sharing is the best way to encourage healing.

“Of course, there was just a tremendous amount of sadness,” he said. “The healing process is not either/or. You never ever completely heal, but you also don’t hold onto the pain in the way that you did at one point.”

The 9/11 attacks changed the country forever and are part of our collective consciousness, even after 12 years.