Kim Jong-il Was Not My Homie & WTF Is Gangnam Style?

By Jake Fredericks

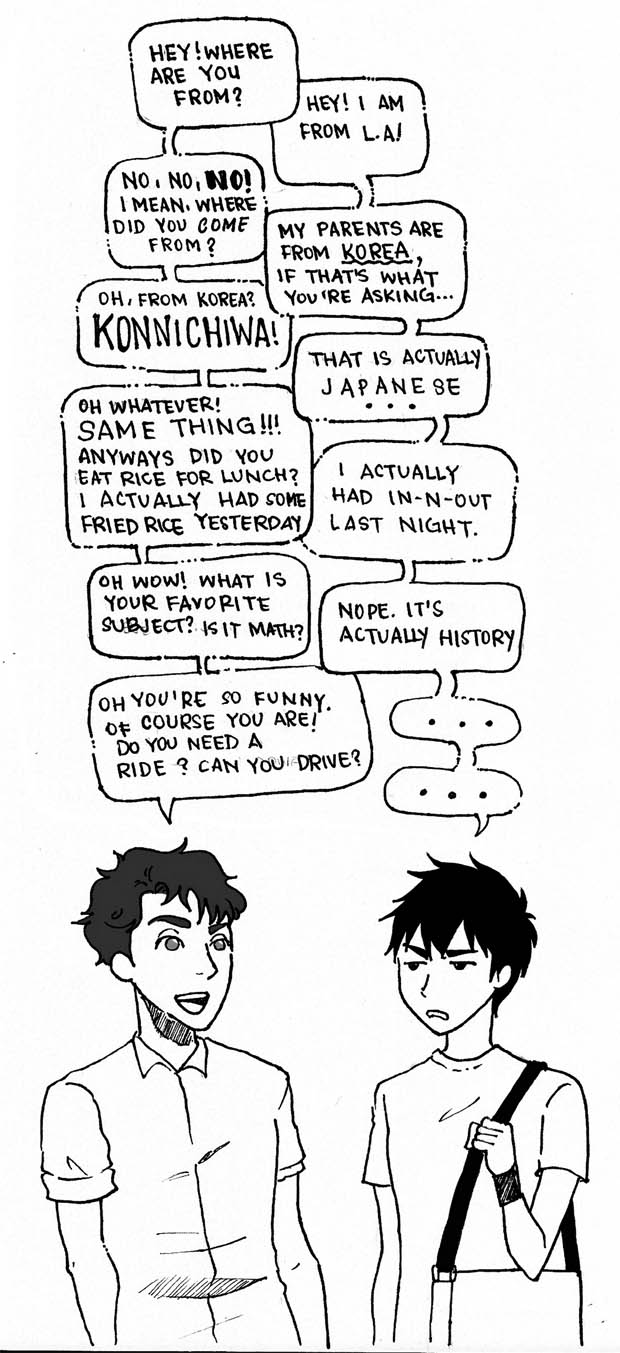

First, let’s get a few things straight. I am not good at math. I do not drive my car 10 miles per hour under the posted speed limit and I do not know any form of martial arts.

Yes, I can use chopsticks, but I’d be willing to argue that equal amounts of people are able to wield a fork and knife. You don’t see me asking white people if they’re all cowboys.

The point I am trying to make here is that Asian-Americans, and minorities as a whole, are constantly discriminated based on [our] appearance. This predilection for accepting and proliferating racial stereotypes and cultural roles is damaging to a nation comprised mainly of the so-called minorities.

Additionally, the term “Asian” itself, is a social discrimination concocted to oust an even more bigoted term, “Oriental,” meant to encompass all Asiatic races. But, for the sake of continuity, I will henceforth refer to myself– the Asian minority– as Asian-American.

In an April report from the Pew Research Center, immigration data compiled from 2000-2012 showed Asiatic races leading immigration into the United States.

“Asian-Americans are the highest-income, best-educated and fastest-growing racial group…they place more value than other Americans do on marriage, parenthood, hard work and career success,” reported Pew Research experts.

However, not all Asian subcultures share a uniform success rate in education and economic wealth. A report from Asian-Americans Advancing Justice- Los Angeles found that a mere 58 percent of Cambodian residents in LA have an education (diploma) equivalent to a high school level. The skewed educational data due in part to the fact that over half of all 1 million Asian-Americans in Los Angeles cannot speak English proficiently.

By definition, a minority is the group that is the smaller number of a larger group. Typically, this way of categorizing minority groups is factored by the ratio of white to non-white. However, the minority group within a city such as Chicago may be different to that in Eureka, CA.

Furthermore, racial stereotypes are commonly drawn from previous generations of afflicted minority groups. In the same way biological twins may appear identical but act different, specific races do not share a universal mindset.

If I had a dollar for every time a person gave me a shocked look when I told them I have adoptive Anglo parents, I’d be a millionaire. As if I was only expected– allowed– to have Asian parents.

I was raised in a predominantly white neighborhood where Asian could be classified as a minority group. As a result, the majority of my friends were Anglo-looking or non-Asian individuals. However, just because I had white parents, and lived in a white community, and had mostly white friends, it didn’t lessen the blows of an Asian stereotype thrown at me from time to time.

I was (I am) still Asian. Race is not an attitude– you can’t roll out of bed in the morning and tell yourself to be someone else for the day.

As I got older, I began to embrace my identity as an Asian-American, and I realized that it made me a more accepting and less judgmental person. Being raised by Caucasian parents has given me a unique perspective on how minorities within different social circles are represented, and accepted.

I strongly believe that nurture comes before nature. My unique upbringing is translated into everything I am and everything that I do when it concerns my personal identification. I prefer to consider myself an American-Asian more than Asian-American, because I choose to identify myself more in the context of my social setting, than I do with my biological composition.

I am an American. I am Asian. I am a brother. I am a son. I am a student. I am an employee. I have good days and I have bad ones, too. I cry. I bleed. I laugh and I dream.

I am, and I do, all of these things.

In short, I am just like you.

There is no universal Asian-American identity

By Calvin Ratana

“Arigato,” said a customer at the restaurant I work for. “Is that correct? Is that how you say it?”

Every time I go to work, I never fail to hear those lines. To be fair, I do work as a sushi chef at a Japanese restaurant. However, I still cringe a little whenever a customer pulls those lines on me.

When broken down, my story speaks volumes about the general attitude Americans have toward Asian-Americans. All Asians are the same. We all share the same culture, language and lifestyle. Oh and that we all look the same.

However, all these assumptions are wrong.

To the media and entertainment industry, we are all the same. For example, in the movie “Hangover 2,” Jamie Chung and Mason Lee, a Korean-American and Taiwanese-American respectively, plays the role of Thai characters. Because to the media Thai and Korean are just the same thing: Asian. I mean we all look alike so it doesn’t make a difference if another Asian portrayed another Asian, right?

Wrong. Furthermore, Chung and Lee’s characters get very little screen time. To top it off, Chung’s character is the submissive Asian woman stereotype while Lee’s character is the stereotypical nerd, innocent Stanford student. Because to the media, Asian-Americans are placed in two roles: the hypersexualized female and the desexualized male.

So why this overgeneralization of Asian-Americans? Simple: the model minority myth. This myth emerged back in the 1960s with Asian-Americans gaining high test scores and grades in school as well as having a high university attendance rate. The myth displayed Asian-Americans as successful, obedient, quiet individuals who are pulling themselves up by their bootstraps.

However the myth collapses on itself. No, not all Asian-Americans are good at math and science. And no, not every Asian-American is successful in America.

There are dangers in the generalization of Asian-Americans. Because of the myth and the media, achievements of more successful individuals often overshadow the problems that other individual Asian-American & Pacific Islanders (AAPI) face.

So no, not all of us are “smart.” According to a recent report that Asian Americans Advancing Justice-LA (AAAJLA) released, only 58 percent of Cambodian-Americans in the LA County have a high school degree. Only 13 percent of Cambodians have at least a bachelor’s degree. And still to this day, AAPIs ages 25 or older combined are still less likely to have a high school diploma or GED as compared to whites.

In short, AAAJLA’s report finds that on average AAPIs in LA County make about $28,000 a year while their white counterparts make about $47,000 a year on average. According to AAAJLA’s report, in LA County, the three ethnicities with the lowest incomes are Tongans, Cambodians and Samoans. Tongans average roughly $8,100 a year while Cambodians average about $14,200 a year. Samoans aren’t far behind with an average income of $15,350 a year.

In fact, AAAJLA’s report finds that 78 percent of Tongans are low income while 51 percent live in poverty. The report also finds that 23 percent of Korean, 19 percent of Cambodian and 17 percent of Chinese-American seniors in the LA County are all living below the poverty line. According to AAAJLA, that is “a proportion greater than all other racial groups.”

And from 2007 to 2011, the number of Asian-Americans living in poverty in the LA County grew by 20 percent. Pacific Islanders living in poverty increased by 84 percent.

The AAPI population is not one autonomous unit bent on being obedient to the white hegemonic structure. We are a diverse group of people with different lives and stories. It is wrong to group all AAPIs together. It is not only just flat out racist, but will only continue to overshadow the problems that many Asian-American and Pacific Islander groups face in America.