Denied from four different CSU schools including Northridge, a low-income and first-generation art student relied on his acceptance in the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP) to attend CSUN.

Denied from four different CSU schools including Northridge, a low-income and first-generation art student relied on his acceptance in the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP) to attend CSUN.

Each year EOP accepts special admits – students that are judged as unqualified by CSU admissions, but exhibit high academic potential. Thomas Kollie is one of the special admits accepted in 2010.

“(Being part of EOP is) probably the greatest experience of my life. The different areas I grew up in – there were people that wouldn’t tell me I could go to college or people who wouldn’t influence me to go to college,” Kollie said.

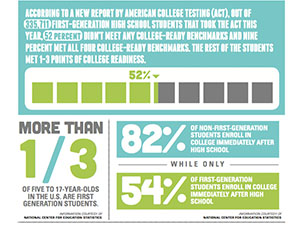

According to a new report by American College Testing (ACT), out of 335,711 first-generation high school students that took the ACT this year, 52 percent didn’t meet any college-ready benchmarks and nine percent met all four college-ready benchmarks. The rest of the students met 1-3 points of college readiness. The four college-ready benchmarks tested were English composition, social sciences, college algebra, and biology.

A part of EOP services creates intensive summer courses and workshops for incoming low- income and first-generation freshman designed to prepare them for college. The students who tested into courses below college level, like Math 92 or Writing 113A, receive an opportunity to complete some developmental courses through EOP transitional programs such as Bridge programs. Students who tested into college level courses attend the Fresh Start Program.

“The support services go all the way from mentoring programs to tutoring to advising. Everything that students need to make their way through college,” said Glenn Omatsu, coordinator for the EOP Faculty Mentor Program and Asian-American studies professor. “This is essential for first-generation students because somebody who comes to college who has (family members that are college graduates) already get informal advice.”

Prior to World War II enrollment in U.S. colleges, by and large, was not inclusive to poor, working class and people of color. However, the GI Bill and the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s changed the student population. Within the Civil Rights movement, there were student movements that created EOP and ethnic studies on campus.

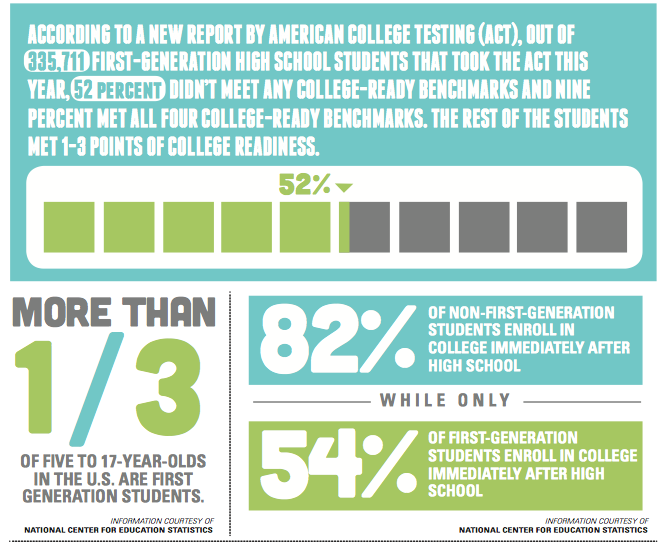

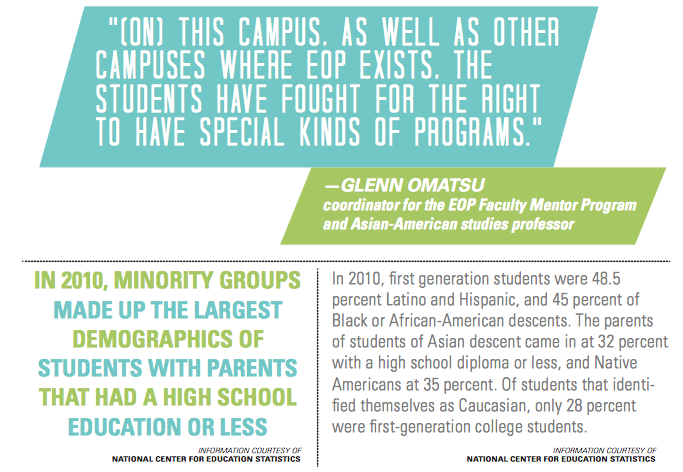

“If we take a group who doesn’t have parents that went to college, as a result how would they find out about college?” Omatsu said. “(On) this campus, as well as other campuses where EOP exists, the students have fought for the right to have special kinds of programs.”

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, more than one-third of five to 17-year-olds in the U.S. are first generation students. While 82 percent of non-first-generation students enroll in college immediately after high school, only 54 percent of first-generation students do the same.

The TRIO programs housed in the Student Outreach and Recruitment Services office is a federally funded college opportunity program that focuses on first-generation students in middle schools and high schools in the San Fernando Valley. The programs were part of Lyndon B. Johnson’s war on poverty legislation.

Upward Bound TRIO provides instructions on various academic subjects after school, weekends and during the summer. They offer a six-week program where high school students take courses and remain in the dorms for three weeks. Talent Search helps sixth to 12th grade students in the San Fernando Valley get information about financial aid, scholarships, and college admissions to public, private, two-year and four-year postsecondary institutions.

“Since a lot of these families don’t know how to navigate the education system it may be totally different than their own countries. With these programs we are here to be that support system and guidance towards that information,” said Evelyn Torres-Garcia, director of TRIO programs.

From the students in two of the TRIO programs, Torres-Garcia notices a common self-doubt..

“Those self-doubts of whether you will be able to make it if you go to a four-year, that’s one of the things that we try to talk to them about as well. It’s that fear of ‘what if I don’t know anybody and what if I can’t do well,’” Torres-Garcia said.

Veronica Sullivan, psychologist for University Counseling Services, agrees that first-generation students are less confident in a classroom setting.

“Academically, first-generation students often come into college feeling less confident and less prepared academically. In particular, they may avoid certain majors, such as science and math and may have lower academic aspirations,” Sullivan said. “They may have received different messages growing up about the importance of college and of a degree.”

As a first-generation undergraduate who didn’t belong to EOP because it didn’t exist yet, Omatsu feels fortunate that he attended a community college.

“That probably saved me because if I had gone to a four-year institution I probably wouldn’t have made it because even though I had fairly good grades during high school I had no idea what college was about,” Omatsu said.

Although not all first-generation students are part of EOP or TRIO programs, courses—like University 100—focus on skills and resources needed to succeed in college and are available for any student.

In addition to academics, Sullivan said first-generation students face cultural, social and financial problems as well.

Omatsu comes across students who don’t have money to purchase textbooks, food, or pay rent because they feel an obligation to share their financial aid with family member that are affected by the economic recession.

“When you think about it, financial aid isn’t a lot that the students receive. It’s just barely enough to cover things. When you think about somebody that is also taking half their financial aid and giving it to their families, then you understand the special kind of hardship that the student faces on campus,” Omatsu said.

Programs for first-generation students aren’t distributed evenly throughout all universities. Although state legislature mandated CSUs and UCs to establish EOP, the program is non-existent or differs from campus to campus.

“Because of internal conflicts, differences in each college campus, and state politics—for example California had in 1996 the end of affirmative action. With the end of affirmative action some UCs used that to eliminate EOP programs on the grounds that EOP was seen as more of a race based program even though it isn’t,” Omatsu said. “They were able to use that to eliminate or reorganize EOP. In the CSUs, it has to do with the strength of the student movement on each campus. Also, how well EOP has been able to defend its mission.”

TRIO experienced a 5.23 percent budget cut for the fiscal year. Lack of funds resulted in the loss of two out of the six programs: McNair Scholars and Upward Bound Math and Science.

Omatsu sees problems with kindergarten to 12th grade education but he disagrees with those that don’t believe a four-year university should take the responsibility of dealing with that problem.

“I disagree with those who say it’s not our role to do that. I think that we have an opportunity to unleash potential in a lot of people to help them move forward. These are going to be our future leaders. These are going to be the people in positions of power,” Omatsu said.