In the newsroom at the Daily Sundial we often talk about the concepts of balance and objectivity. Reporters and editors have always shared opposing arguments. Our stories are an extension of this discourse. But it’s not our fault.

We are conditioned

We are all conditioned, and we are taught that we are not conditioned. Especially journalists.

Those of us that have decided to pursue journalism as a discipline are conditioned to seek a readily-available truth. We are told to give opposing viewpoints equal time, that is, to be balanced.

Professors tell us we have to keep our opinions out of the story. It’s news, they say. God forbid you use any pronouns referring to you as the reporter. It’s only he, she, him, her, they. It’s never us, we, you, I. Just state the facts, and move on. Don’t take a side.

We are conditioned to give equal time to opposing viewpoints.

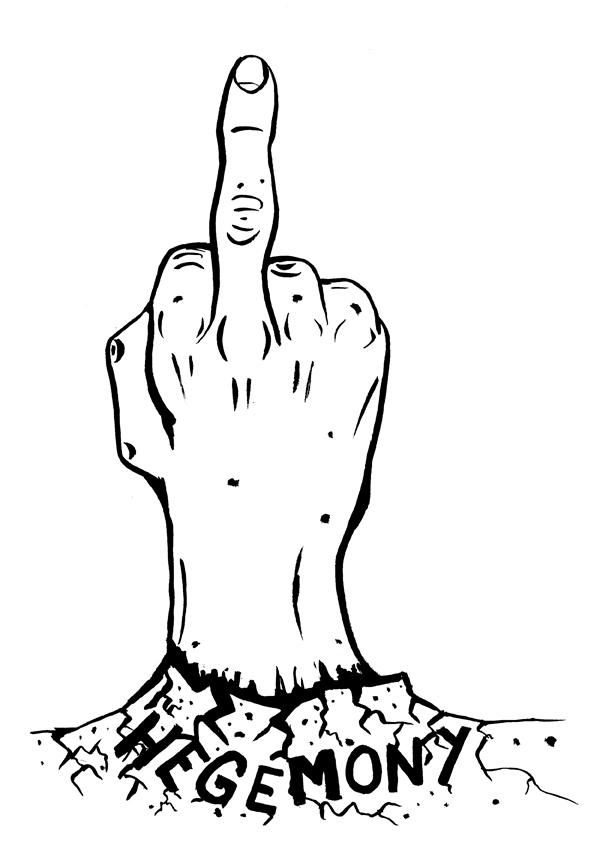

But if your position in society is at the losing end of oppression, the oppressor’s viewpoint has been given enough time and coverage. Six corporations control 90 percent of the media, according to research published in the Business Insider. The status quo remains the status quo because of the nature of their position in power: it’s comfortable, and they only let friends and family in. Like a hegemonic dynasty.

The nature of hegemony

The balance of power is against radical criticism. Hegemony doesn’t stop at the barriers of a supposedly free press. Hegemony goes into the very fiber of our way of thinking.

So, then, it should be no surprise that when you decide to major in journalism, you are inundated with the concept of objectivity. But who do we serve, directly or indirectly, by not questioning the structure of our society?

Injustices by large are not solely determined by individuals so punishing individuals does very little to remedy larger-scale problems.

For African-American males in their 30s, one out of 10 are currently in prison or jail on any given day, according to the criminal justice reform advocate The Sentencing Project.

Federal laws that differentiate between crack and powder cocaine are another example of structural injustice. In 2006, 82 percent of people convicted under federal crack cocaine laws were African-Americans, and including Latinos, the percentage is 96 percent, according to the NAACP.

Instead of questioning why people abuse drugs, why there is a federal differentiation between crack and powder cocaine, how black and brown communities are affected, we don’t question this. We don’t question the prison, criminal justice system or the federal government. Instead, we blame individuals.

Challenging the status quo

Ulrike Meinhof, late journalist-turned-revolutionary, used journalism to expose injustices. She left the journalism profession to join the West German urban guerilla the Red Army Faction, putting into practice what she was writing about, exposing Western imperialism, the Vietnam War and denouncing capitalism that indoctrinates us into catatonic consumers.

In “Occupy: Class War, Rebellion and Solidarity,” a book written by critically acclaimed political commentator Noam Chomsky, he examines mainstream media’s uncritical commitment to objectivity.

“If you go beyond that and you ask a question about the bounds, then you’re biased, subjective, emotional, maybe anti-American, whatever the usual curse words are. So that’s a task and, you know, you can understand it from the point of view of established power,” Chomsky said.

But don’t just leave it to the radicals.

Internationally renowned mainstream journalist Christiane Amanpour, who I disagree with on most political issues, once famously said, “There are some situations one simply cannot be neutral about, because when you are neutral you are an accomplice. Objectivity doesn’t mean treating all sides equally. It means giving each side a hearing.”

The crime and immorality of objectivity

To side with objectivity can actually mean to be complicit. The reporter who refuses to question the rising incarceration of black and brown youth in urban communities while acknowledging influence of policy in the criminal justice system by the Corrections Corporations of America is guilty of complicity.

And although Pennsylvania Luzerne County Judge Mark Ciavarella Jr. was sentenced to 28 years for sending boys and girls to juvenile detention centers in exchange for bribes from these same companies, it is not an isolated incident. The entire U.S. political economy, from its courts to its institutions, is corrupt.

In fact, the only reason stories of corruption such as these are made public by a supposedly investigative and critical media is to perpetuate the idea that we live in a functioning democracy. In other words, the system is fine; Judge Mark Ciavarella or AIG, Lehman Brothers, Chase and other financial institutions guilty of mishandling money and other crimes are only examples of bad apples.

But in reality, no, the entire apple orchard is rotten.

Famous late journalist, Rubén Salazar, a hero of mine but not a radical by any means, was once quoted as saying, “Objectivity is impossible.”

In journalism, objectivity is fetishized. It is made into something that is desired and erroneously attainable.

When photojournalist Kevin Carter documented the 1993 famine in Sudan, he came across a starving child struggling to get to a feeding center over a hill.

Far off into the background of the child settled a vulture, like a patient guest waiting for his meal. Carter snapped this iconic photo, which later won the Pulitzer Prize.

The photo and photographer came under much controversy. Many critics said that Carter should have picked up the child, but that ultimately due to his journalistic duty, he did not. There are many accounts of the story. But what remains is this: the fate of the child is unknown, the journalist community was by and large passive when it came to calling for their readers to get involved, to question the origin of the famine, the parties involved and those that remained silent.

Carter, shortly after winning his Pulitzer Prize, committed suicide. I would venture to guess that when he thought of the concept of objectivity and the role of journalism, he didn’t like the answer he came up with and, so, to save his soul he took his life.

But I’m not Carter, nor do I want to be.

Why major in journalism?

Why am I here?

Why did I major in journalism? Why did I abandon my comfortable full-time salary to go back to school, living on a fixed income slightly over $900 per month, only to discover that I fundamentally disagree with nearly the entire discipline of contemporary journalism?

Stephanie McMillan, former journalist and radical activist, visited CSUN this past October showcasing her political cartoons and spoke out against capitalism and imperialism. When I spoke to her, it was clear she understood the role of the media and our role as activists.

“If you live in a class society, there is no such thing as objectivity,” she said. “Because most of what’s promoted and talked about and put out in the media is serving the ruling class. If we’re actually going to promote balance, then we have to decide who we are serving. And I believe, like you do, in serving the oppressed.”

I decided years ago that life isn’t worth living if it isn’t adding significantly to a movement to better the lives of the people most afflicted and oppressed, locally and globally, and that my ultimate happiness is directly tied to the well-being of the most affected by the cruel political economy of capitalism.

And I’ve been told I have a knack for writing. Naturally, I am trying to merge my talent with my calling. Come what may, I’ve made my peace. I will never be hired as an objective journalist. I don’t want to be, and that’s OK. Surely, this article will come up with a simple Google search of my name by prospective employers. That’s fine. We should be honest and transparent. I do not want to perpetuate U.S. capitalist and cultural hegemony. Frankly, I want to contribute to its destruction.

So, journalists and non-journalists, do what you will, but understand the true role of the media. We are not here to protect you. We are here to distract you.

But I am here for something else.