The discussion of police brutality against black americans, in the wake of the high-profile deaths of Freddie Gray, Mike Brown and Trayvon Martin, continues to affect the public discourse through the Black Lives Matter movement and its social media manifestation, #blacklivesmatter.

On Thursday evening, several members of the CSUN student and faculty community came together to bring that discussion to the local public and openly discuss police brutality with members of the Los Angeles and campus police departments.

Organized by the CSUN Black Male Initiative, the event was a continuation of open discussions begun last year, according to BMI staff adviser Sam Prater.

“Last fall we had a conversation about race in the dorms and about 300 students came,” said Prater in an interview after Thursday’s event. “It was cathartic for students. It was informative because we had some dedicated faculty that stayed until 10 p.m. for a three-hour program talking about it. So this in a way is a follow-up to that conversation.”

One of the event’s featured speakers was Roy P. Crocker Professor of Law at USC Jody David Armour, who has written and studied issues pertaining to police brutality and racial profiling. Armour also screened a short, biographical film documenting his experiences and thoughts on being profiled for his physical appearance as a black man – most notably for his ostentatious hair style.

At the core of Armour’s remarks was the discussion of the Black Lives Matter movement as a united response to the failure of the criminal justice system.

“The Black Lives Matter hashtag shot up when the state, through the criminal justice system, through a trial, acquitted Trayvon Martin’s killer [George Zimmerman],” said Armour. “It was just like in LA when Rodney King was beat down.”

“But they did not take to the streets,” he added. “What did they do? They waited for justice. And they only took to the streets after the acquittal of officers seen on the tape.”

But during the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and hashtag, reactionary movements such as #AllLivesMatter entered the picture. Some CSUN students in attendance expressed their exasperation and annoyance over how such reactionary actions shifted the Black Lives Matter discussion.

“I’m tired of seeing all these people die, I’m tired of seeing these hashtags [and] I’m tired of seeing all these different situations where we have to have these discussions,” said CSUN student Josh Briggs to members of the discussion. “And the concept of ‘all lives matter,’ yes it’s true, but the only reason we’re having this discussion is because black lives are being affected.”

Others vocalized their aversion to the inclusion of the hashtag #AllLivesMatter on posters and graphics used to advertise the event.

Assistant Commanding Officer for the LAPD Valley Bureau Regina A. Scott echoed similar comments.

“I think all lives do matter, but I do think if you’re going to make a point and you’re trying to address a cause, and the cause is black lives that are being treated disparately or being harassed by the police, then you have to understand where you’re going with it…with all lives [matter],” said Scott after the event. “But I do think there is a distinct difference because you are talking about issues that are happening…in the nation today.”

Prater later apologized on behalf of the BMI for the decision to include this hashtag, though it was not made clear who had collectively made that choice.

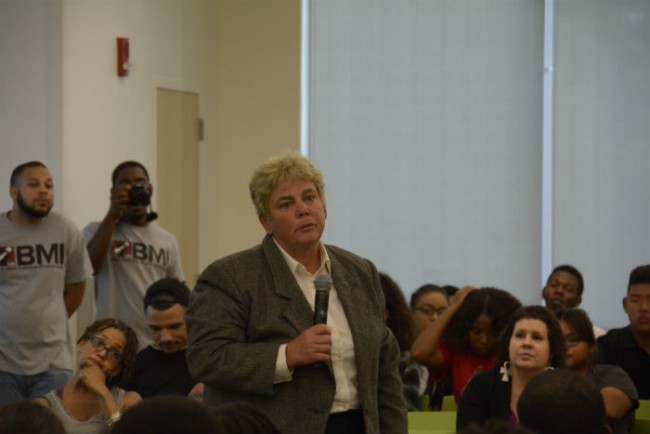

CSUN police chief Anne Glavin spoke on behalf of CSUN’s law enforcement presence.

“I’m really sad and embarrassed for my profession,” Glavin said to the crowd. “Let me tell you however, these types of situations give us the opportunity to look inward…and say what are we doing? How are we doing it? What is the difference between what is legally right and correct?”

Glavin also explained how recent, high-profile deaths of black americans were a result of bad cops and that the majority of police across the U.S. were among the ones who wanted to do some good.

But this point was made in contention to an idea made by Armour – that many people, including the police, were subject to making decisions through “unconscious bias.”

There’s a lot of research that talks about, at the cognitive unconscious level, how you can have subjects look at two people engaging in the exact same thing and if one of those people are from the outlier – black for example – they will systematically interpret their behavior as more hostile, violent and wrong than similarly situated whites that are making the same behavior,” said Armour.

“And it’s all happening at the unconscious level,” he added.

Regardless of conscious or unconscious bias, the end result was the same for many black CSUN students who related personal experiences of being stopped by police for the way they look.

“Everyday, growing up as a youth, going to high school, I got stopped by the police because of a profile I fit. I graduated with a 3.8 GPA…I’ve never got in trouble [and] I have a clean record,” said BMI president and CSUN student Wesley Williams. “But I was getting harassed everyday by police because of what I look like, because they’ve seen somebody who looks like me, dresses like me [and] do bad things before.”

Despite those experiences, Williams believes more engagement between police and the black community is necessary.

“We have to stop this notion of ‘F— the police,’ that disengagement from the police,” added Williams. “Policies need to get changed from a level way higher than where we stand, but at the lowest level is the police and they’re the people enforcing the law. So more people who look like us are enforcing the law, we might feel more comfortable, we might feel less threatened and the statistics might drop.”