>>Some names have been changed to protect identities.

For Rich Foster, life was not something to be happy about. Thoughts of self-contempt and guilt were ever-present companions in his daily life.

Though he managed to get up every morning and face the day ahead, a repeated discontentment with his life took a toll, and his depression became integral to his being; the norm. The chance of overcoming it seemed more unlikely every day.

Foster, a 22-year-old former CSUN student, battled with depression and thought there was no way out.

“Typically, depression involves feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, worthlessness and guilt,” Foster said. “The last two — feeling worthless and guilty — are the feelings I battled most.”

He viewed his depression as being stuck in a negative circle. The feelings were so intense, he just figured it was part of his personality.

“It wasn’t often that I was so depressed that I couldn’t get out of bed. I just wasn’t happy with my life, and couldn’t find my way out of the rut that I was in,” Foster said.

The fear of being labeled and perceived differently kept him from talking about it and from seeking help and treatment. Entrapped with his depression and no means of managing it, thoughts of suicide began to invade his mind.

“I have contemplated suicide and have even gone as far to have planned it out,” Foster said. “Not being afraid to talk about it is a big step for me.”

Studies have shown that Hatoonian is far from alone.

The battle against depression is a struggle. A struggle an estimated 1-in-10 Americans deal with, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. An American Psychological Association (APA) study shows that 53 percent of college students have experienced some form of depression.

But many suffer in silence.

Over two-thirds of young people do not talk about or seek help for mental health problems, according to Psych Central.

Foster never viewed his condition as an illness until his sophomore year in college, when he saw a Blues Project presentation. It was not until then he realized that his depression could be overcome, and that help was available.

Seeking help is crucial, as depression can lead to thoughts of suicide. Nine percent of those participating in the APA’s study revealed that they contemplated suicide at least once since beginning college.

An American College Health Association report found that 1.5 percent of 16,000 students have attempted suicide.

Marshall Bloom, University Counseling Services (USC) psychologist and head of the Blues Project, a group that conducts presentations on depression to classes on campus, is concerned with the lack of discussion about the subject.

“I’m surprised with how accurate the numbers are,” Bloom said. “Fifteen to 20 percent of students suffer from depression, and one percent will attempt suicide.”

In 2008, suicide accounted for about 36,000 deaths, making it the 10th-leading cause of death in the U.S., according to the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. It was ranked third among those age 15 to 24.

“Over the years, I have seen anxiety and depression rise in prominence, as well as the levels of psychological distress,” Bloom said. “Depression is treatable, and suicide is preventable.”

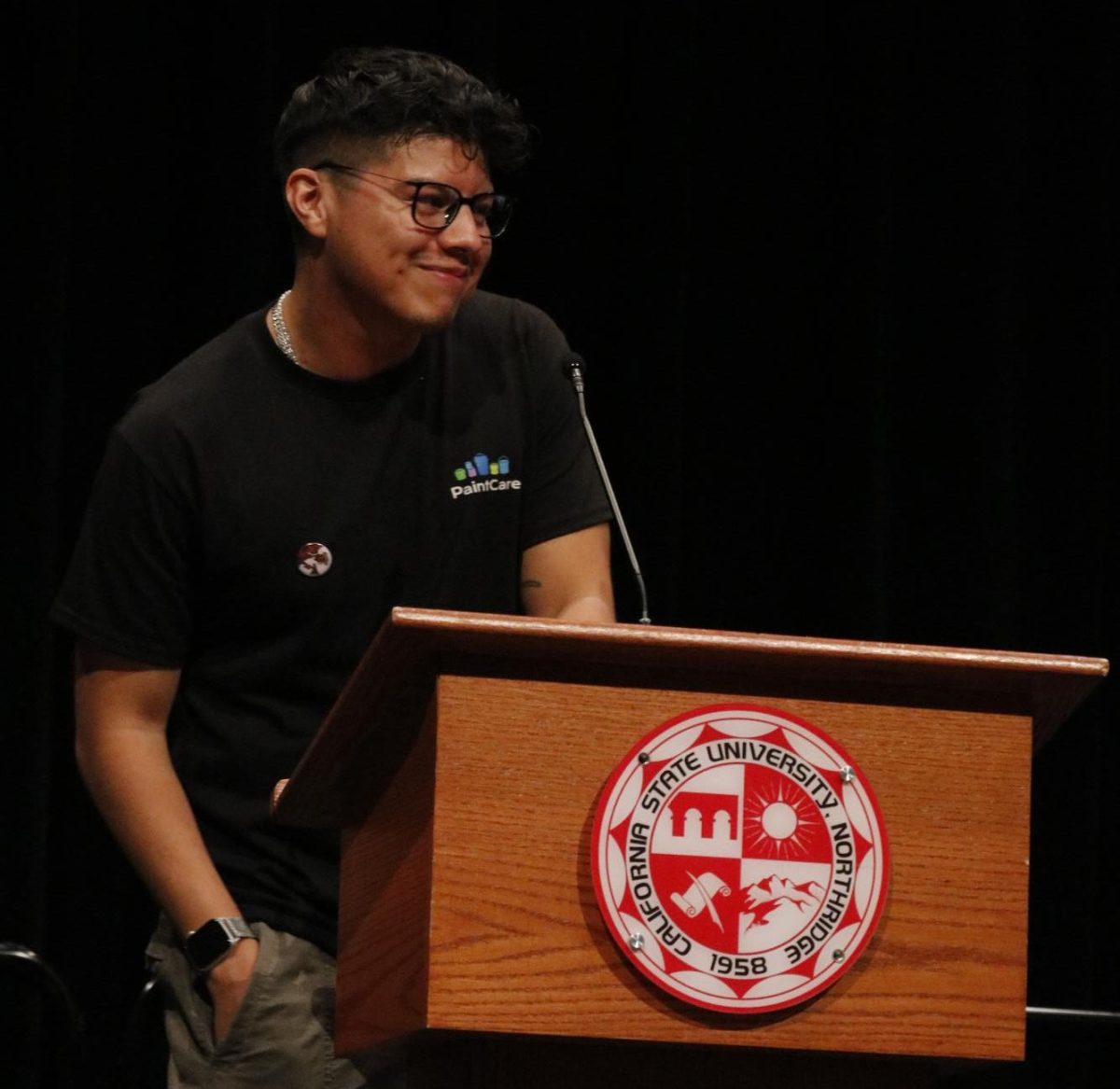

Members of the Blues Project Ashley McCort, 22, Luis Canton, 20, and Emily Shigenaga, 19, had encounters with depression before they joined the project and became mentors.

McCort joined in her fourth semester at CSUN to understand more about the subject.

“Some of my family members were depressed, and I could not help at the time,” she said. “The information was empowering, and I like giving it to others.”

Canton wants to help overcome the stigma of being depressed and seeking help.

“This is a topic I hold very dear to my heart because I personally suffer from depression. It is a problem, and has the potential to get worse,” said Canton, who lost a close cousin to depression last year and has friends who have contemplated suicide.

Shigenaga learned about the Blues Project her freshman year, and instantly connected with the message. She lost a relative to depression in 2009.

“At the time, I was unaware of her depression, and did not see any warning signs of suicide,” she said. “I was struggling to understand why she (her relative) took her life. I would hate for any of my peers to lose a loved one to suicide and carry the same guilt I did because they weren’t able to provide an ounce of help.”

Shigenaga believes that there is nothing to lose in going to a counseling session at the UCS.

The counseling service is free and confidential; the UCS website notes that its records are kept separate from academic records.

Currently enrolled students can take up to eight free counseling sessions at the UCS per academic year, with a one-to-two week wait for the first appointment, according to the UCS website.

If students need additional counseling the UCS then makes referrals to nearby counselors and clinics, said Mark Stevens, director and psychologist of UCS.

“We see about 50 new students per week for the free service,” said Stevens in an e-mail interview.

Foster said he understands that the leap to seek help can be daunting, as many factors contribute to depression.

Culture has a lot to do with it, he said, as many Latino, white and black cultures see counseling as negative.

He said regardless of culture, students’ lack of understanding of what counseling is keeps them from going. After abandoning his fears and apprehensions, he made an appointment for his first session.

“I was really surprised by the sessions I went to. I did most of the talking in those first few sessions,” he said. “There was hardly any mention of the term depression. The sessions were more about my problems, and what practical solutions we could come up with to solve those problems.”

Foster remembers the sense of relief by venting during his first sessions. There were hardly any questions at first, and the questions asked were general. He could answer as freely as he wanted to, no longer nervous after being told everything was confidential.

“We eventually got to a point where (the psychologist) was helping me notice certain patterns in my life that really contributed to depression,” Foster said. “I got to address those problems in my life, and I would go back to my counselor every so often to check in what worked and what didn’t. It was all surprisingly straightforward.”

The fear of being labeled prevents people form seeking help, he said. He suggested students not ready to seek professional counseling should talk to someone they trust.

“I don’t want to make it seem like counselors and therapists have all the answers. In fact, my counselor and I would often joke about that, because they really don’t have the answers,” Foster said. “What matters most is that they talk to someone.”