In the wake of the #MeToo movement, artists and professors of the CSUN campus join the conversation on whether it’s possible to separate an artist’s work from their controversial biographies.

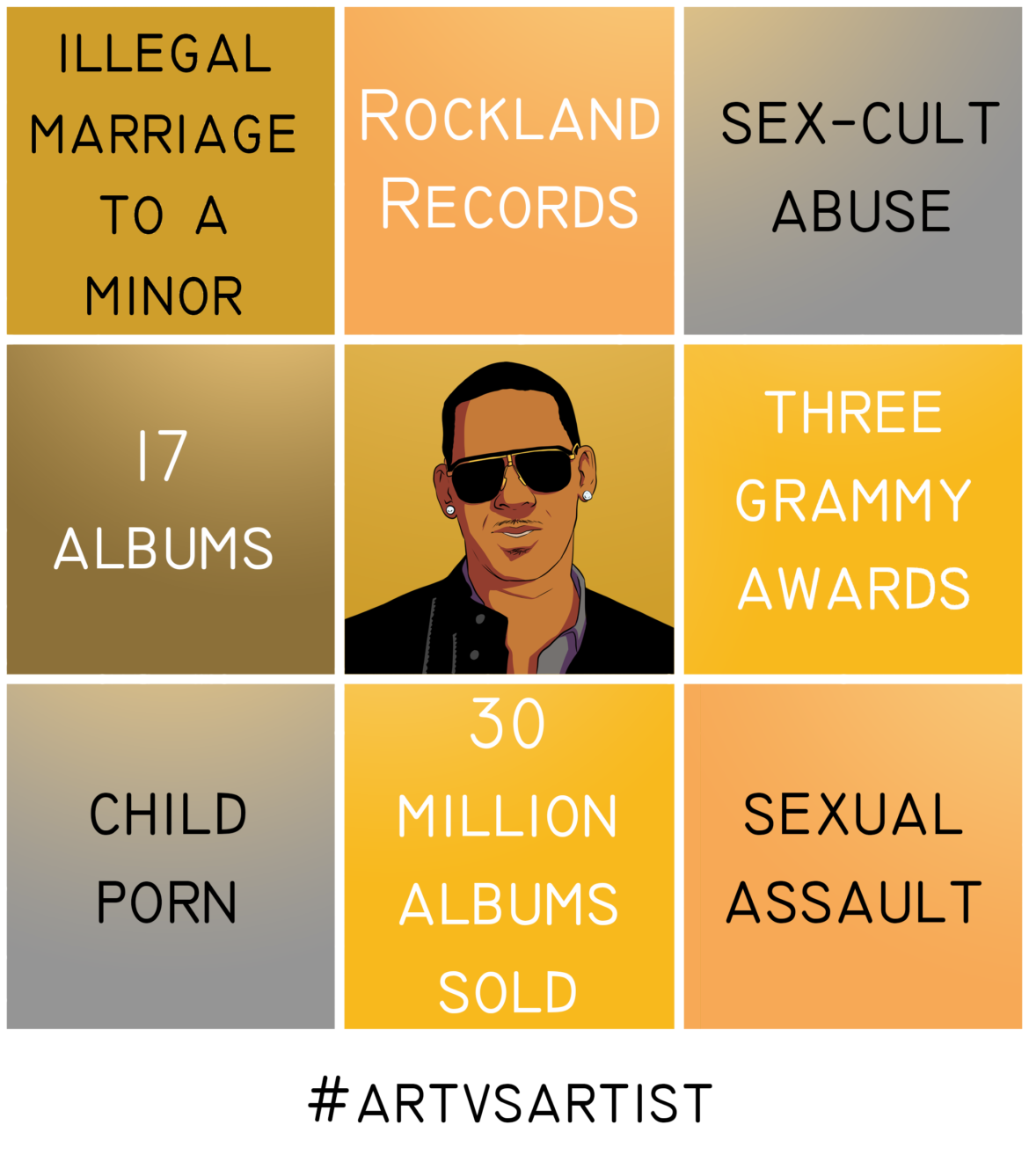

During the past few years, sexual abuse allegations against many artists and entertainers have been exposed by news outlets and social media. The most recent notable allegations were aimed at R. Kelly in a six-part Lifetime documentary series titled “Surviving R. Kelly.”

The documentary series averaged more than 2.1 million viewers in the U.S. As a result many artists, including Lady Gaga, have distanced themselves from Kelly and have expressed remorse for working with him.

Music streaming services such as Pandora, Spotify and Apple Music have stopped promoting his music, and many artist collaborations have been removed at the discretion of the artist. Kelly has suffered financially from these actions, as his record label, Sony Music, has also canceled his recording contract.

Kelly is just one of the many mainstream celebrities who has been accused of sexual abuse. The New York Times exposé on Harvey Weinstein’s sexual abuse allegations, published in October 2017, propelled the #MeToo movement. The movement went viral, and more women came out to share their accusations using the same hashtag.

A few others include Bill Cosby, who was accused by 60 women of sexual abuse, and Kevin Spacey, who was accused of sexually assaulting underage boys. As a direct result, Spacey was removed from the hit Netflix show “House of Cards,” and Cosby was sentenced to state prison.

In the music industry, the late XXXTentacion was accused of domestic violence and the alleged battery of a pregnant woman. Tekashi 6ix9ine is another musician who was accused of sexual crimes. 6ix9ine, however, pleaded guilty to three felony counts of using a child in a sexual performance. XXXTentacion’s music was no longer being promoted, and 6ix9ine was sentenced to four years of probation and 1,000 hours of community service.

Despite all the allegations and consequences, artists who have been accused of sexual violence are continuing to make art flourish. The question then arises: Is it possible to separate the art from the artist?

Cassandra Koukourikos, 20, has been singing since her exposure to traditional Byzantine chants through her Greek Orthodox church at a very young age. Now Koukourikos has an associate degree in theatre arts from Antelope Valley College and is at CSUN majoring in theatre, with a minor in musical theatre.

“Even though someone may have grown up listening or watching an artist, finding out that the same person has committed crimes that are so egregious … it detracts from the art itself, and it loses some of the previous value it had,” said Koukourikos. “I personally wouldn’t want to value any of their art myself or to hold them on any platform knowing the things they did.”

Jeffrey Izzo, the chair of music industry studies and an assistant professor at CSUN, has an opposing belief. Prior to joining CSUN, Izzo spent over 20 years as a lawyer representing different songwriters, musicians and entertainers. Izzo and Koukourikos both agree that separating the art from the artist is a personal issue.

“It depends on the context of the art, whether someone you know has personally been a victim of similar abuse, or even whether any good can come from that art,” explained Izzo about the different factors that may affect one’s perspective on the issue.

Izzo, however, is against censoring the art altogether, as he said, “I try to look at the art on its own, I don’t want to deprive myself of the art itself.”

Izzo described the problem of sexual abuse as a societal problem, not just one prevalent in the art and entertainment industry, but in almost all male-dominated fields.

The spotlight remains on the entertainment industry because of how transparent it is. To combat these acts of misogyny, Izzo said, “As a society, we must become more sensitive and empathetic, and to believe women when they talk about the abuse they have endured instead of ridiculing or questioning them.”

“If you sweep these things under the rug and act like they never happened, you rob people of some of the greatest pieces of art,” said Izzo.

He does not, however, think we should ignore the acts these entertainers have done.

“It’s important to recognize that these men are scoundrels and even if we cannot look to them for inspiration, their works should not lose any merit, as some of these artists were groundbreaking,” said Izzo. “Just because you champion the good, doesn’t mean you ratify the bad. ‘The Cosby Show’ was the first African American, middle-class show on television, and it was needed. That’s why to me, I don’t think you should minimize that.”

Not separating the art from the artist allows the audience to watch a great entertainer make it to great heights, and then witness them throw it all away at the top, due to abuse. By censoring or sweeping the artist under the rug, it does not allow a person to see the full picture of the artist, and omits valuable lessons from the audience, on how not to behave.

“Freedom of speech and expression can’t only be things we like,” Izzo said. “It has to be stuff we don’t like, too.”