Every Tuesday evening Luis Antonio Pichardo hosts the Conchas y Café workshop at the Chicano Resource Center in East Los Angeles, open for adults interested in developing skills through the arts. During a recent meeting, the evening workshop began with discussing a quote by German playwright Bertolt Brecht: “In times of disorder, of organized confusion, of inhumane humanity, nothing should appear natural.” The group shared their thoughts casually like friends having breakfast with conchas and coffee, but the gossip was focused on their experience living in “times of disorder.”

This type of discussions is usually held in a university setting, but Pichardo’s audience had a diverse age range and knew that not all of them had access to higher education. The quote reminded Fabiola, an elder regular attendee, of the inhumane death of journalist and civil rights activist Ruben Salazar in 1970. Abraham Jaramillo, a younger attendee, was reminded of government dictatorships. Radu, sitting with his toddler daughter, was reminded of his experience during the Romanian Revolution of 1989.

“It needed disorder but organized to disrupt the natural things so that something would change,” he said. “Somebody was creating that dissipation. Disorder doesn’t come unless it’s provoked by something.”

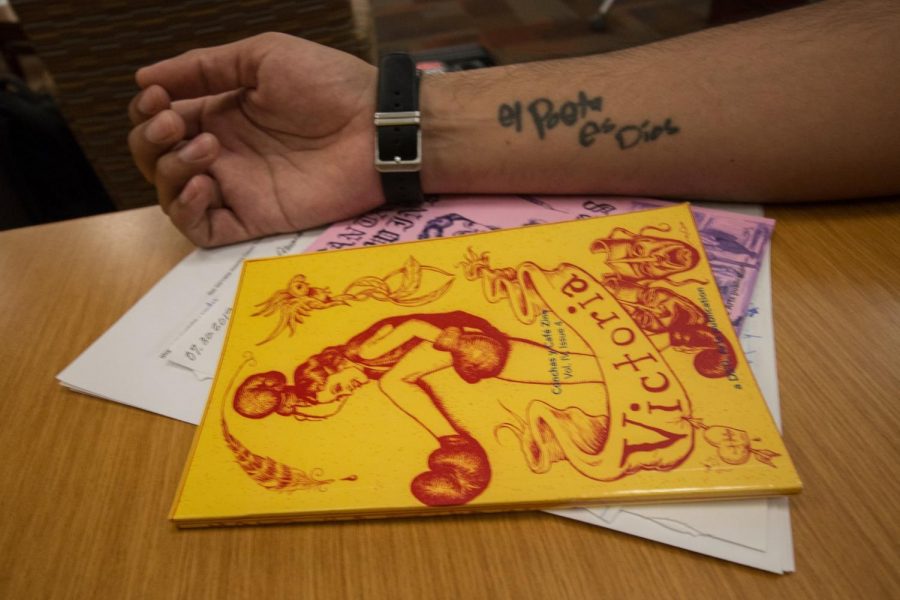

More attendees kept arriving, many wearing clothes from their workplace. One of them was Radu’s wife; while they learned about art, the couple’s toddler would wander through the aisles filled with rich literature, accessible to her just by stretching out her arms. That need for accessibility is what drove Pichardo to create workshops through his non-profit organization, DSTL Arts. Many of the recently-written works engaged in a form of activism with sociopolitical statements and a protest-art approach.

Pichardo finished the discussion by stating that “a lot of the times calls to action use symbols to push us to do something,” recognizing the timeless activist nature within the quote and writing itself. The upcoming artists from the community take what they learn from the workshops and apply it to their visuals and writing, which can eventually be published in the zines DSTL releases throughout the year.

One of the writers taking this direction is Jeremy Arias.

“Like other people (I am also) concerned about the current political climate and it just seems we have a voice. We write down what we think and people can see they’re not alone on this,” he said.

Arias, from Boyle Heights, first got involved through the mentorship program and had a chapbook published. He now oversees submissions from the Art Block Zine for upcoming artists between the ages of 16 and 21.

Even though the zines are not always politically charged, a lot of them end up having a sociopolitical statement to them. One of the zines created by DSTL is NoBias, which mostly consists of protest poetry. The artist residency workshops are usually social justice-based, the most recent one being the No Fake News series in response to this idea of the media in the current administration of the White House.

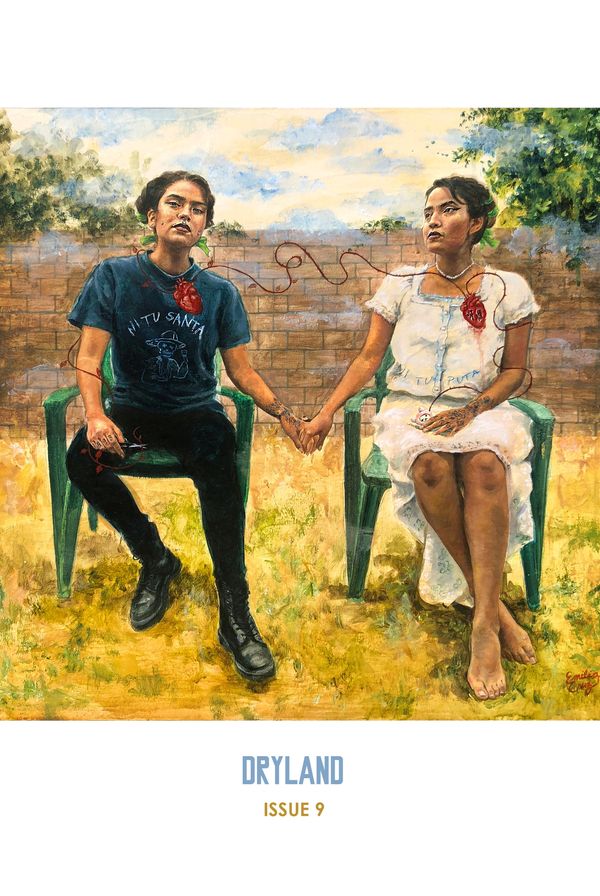

Karo Ska has seen her poetry published in the Conchas y Café zine Vol. 4. One of her most recently-published pieces was featured in the 2019 edition of the literary magazine, Dryland, another community-based platform in South Central Los Angeles. Ska’s poem “Lava-scorched veins > eyeliner” had the following lines: “I don’t show / my regulars the Molotov Cocktail tattoo on my arm. I don’t / tell them I want the world / to smolder. I don’t say in 2014 we blockaded / the 110 freeway for Mike / Brown.” Ska turns to art as a way to heal and as a way to talk about what’s happening in the hopes of inspiring future generations to continue the work if they don’t want to live in a society that’s as messed up as it is now.

Dryland is overseen by founding editor Viva Padilla, who was interested in starting the Dryland series as a platform to express what people feel now. It is not so coincidental, however, that writers choose to write about Trump or other political subjects; the intention to create these kinds of works is there.

“I’m glad people are talking about these things,” she said, “but it should come from a genuine point of view of the writer, it shouldn’t be forced.”

Poet Brian J. Andrade, CSUN alumni, was featured in Dryland, and he engages in activism through writing.

“I write a lot about what it’s like to be working class,” Andrade said. “To this day writing doesn’t prioritize class. It does prioritize race and sexuality but it never integrates that with class and that bothers me. Class affects people’s survival and accessibility to the most basic human needs, even the ability to think in a recreational matter. If somebody has to work all the time they don’t have time to think about fucking Plato.”

Andrade was also a mentee at DSTL Arts during his time at CSUN, where he said he was reading poetry he couldn’t relate to. But at DSTL he found a community around people of similar class with the same aim to be a working writer.

“It showed me that writing could be something sustainable. I could incorporate it in my everyday life and something I can prioritize living in a capitalist society,” he said.

For writers living in underserved communities, Pichardo recognizes that art is not as valued nor supported since it is seen as a hobby rather than a form of employment. According to the 2019 Otis Report on the Creative Economy, 2.6 million jobs were generated within the creative industry, including fine arts and performing arts, fashion, and digital media, among others.

Pichardo, as well as Padilla, have aimed to legitimize the writers’ voices by including an ISBN number on their zines and publications in order to be accepted into branches of the LA public library and local bookstores.

“Zines are typically handmade,” Pichardo clarified regarding the ISBN number. “We’ve been conditioned to believe that’s what makes something valuable. It came more from necessity. The more people started submitting, the thicker it got. Perfect bound books are professionally made but what keeps our publications as zines is the fact that you get to design your page. Every single page in the Conchas y Café zines looks different.”

Similarly, Padilla’s platform is not backed up by an institution nor does she have an academic background. She added, “I’m doing something to counterculture the elitist super-hyper-educated literary scene that’s boring and bland. I’m interested in new ideas, in revolution, Chicano dreams, tearing down the government. I’m interested in freedom.”

Historically, artists have been attacked for critiquing the status quo. According to Chicano artist Harry Gamboa Jr., whose political satire piece is also featured in Dryland, “Art has the potential to affect subjective judgment thereby altering perception, belief in reality, and can also affect language usage thereby determining what will be discussed and what will be ignored. Art has the ability to generate empathy or antipathy in a viewer.”

Altering someone’s perception is powerful for writers, which is why they’re a target in times of oppression. Pichardo and Padilla have seen the positive effect on communities as more upcoming artists continue submitting and attending workshops.

“When I think of other writers that had to be exiled out of the country, someone like James Baldwin comes to mind,” Pichardo said. “He couldn’t (critique the U.S.), his home country. Going to France was a way to feel freer and be critical of the government. (Pablo) Neruda had to go through it as a Chilean writer and journalist, he was very critical.”

Nevertheless, upcoming artists on these platforms feel the sense of importance to continue expressing the political status quo of the country. On that note, Gamboa added, “In the United States, the official support for guns outweighs the valuation of human lives. Art accentuates life. Guns might kill artists where creativity and individuality are not welcome but the art will live beyond the lifetime of mass killers.”

At the end of the Conchas y Café workshop, Pichardo concluded it with a homework assignment: writing a poem about what they considered to be their symbol of power. Soon after, the room emptied out as the attendees went home thinking of the next poem they will disseminate.

“For writers is the dissemination of their work, that is their way of being activists,” Pichardo concluded. “That is how I see our zines functioning. Everything DSTL publishes is all about giving a platform and allowing the community to disseminate their message. That’s the power of publishing.”