“Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire, it has the power to unite people in a way that little else does. It speaks to youth in a language they understand. Sport can create hope where once there was only despair.”

The words of Nelson Mandela have never hit closer to home for the residents of Northridge, California than on the morning of January 17, 1994, when they were woken up by the violent shaking of a magnitude 6.7 quake that ravaged the city.

“It was unbelievable, I lived here in Chatsworth. The house looked like it was just jumping off the foundation,” said Larry Baca, who was then a coach at Northridge City Little League. “I went out front and my swimming pool had water coming from both sides of the house down the street.”

The aftermath of the earthquake was nothing short of devastation. Freeway overpasses collapsed, CSUN was decimated and had to delay the start of the spring semester, and over 8,700 people were injured and 57 dead.

In addition to schools and businesses closing, many residents in the area — including some of Baca’s little league players — lost their homes, forcing them to move and start over. For these kids, baseball suddenly became the only thing that truly felt normal to them.

“A number of these kids had to actually move out of their house because it was damaged so bad,” Baca said. “They had to repair it and it probably took about a year, so a lot of the kids, when they got to the baseball field, they were pretty comfortable.”

As the months passed and the regular season came to a close, the All-Star team was selected, with Baca being named manager of the team.

“A friend of mine … he was telling me, ‘If you guys have any success at all, people are going to be all over you because of this earthquake thing out here,’” Baca said. “And I knew the team was going to be really good.”

The expectations were high for Northridge, who had their sights set on a trip to Williamsport, Pennsylvania for the Little League World Series after they lost in the Western Regionals to Long Beach just two years prior. This team had returned several key players from the 1992 team and they were not going to be denied in 1994.

Northridge tore the cover off the ball all summer, averaging 13 runs per game through the regional round, punching their ticket to the Little League World Series.

“We beat everybody,” Baca said. “We won district, which was Woodland Hills, Encino, and all those places. Then we started getting teams from El Monte and Whittier, and we beat all of them. We went undefeated all the way through. I think we won about 20 or 27 games before we got beat.”

Northridge, representing California and the western United States, lost their first game in Williamsport to Brooklyn Central, Minnesota by a score of 2-4. Baca attributed the loss to the team having jet lag and the game being played late at night in a different time zone.

The team did not have time to dwell on the loss, however, as they played their second game the very next morning.

If Northridge was still tired from having played less than 12 hours earlier, they did not show it in their second game. The offense reminded everybody how dangerous they could be en route to a 6-4 win over Middleborough, Massachusetts.

Northridge shut down their third opponent, Springfield, Virginia, 2-0 to advance to the United States Championship, capturing the hearts of a national audience who had followed their journey as the tournament played out on networks such as ESPN and ABC.

“We started out at Northridge Little League and there were just the families out there,” Baca said. “Pretty soon, there were more people in the stands. By the time we got to San Bernardino, there were like 20,000 people or something out there. We got to Williamsport, they had a lot more.”

The “earthquake kids,” as they came to be known, were now celebrities. With a national championship so close within reach, Baca let the boys have their glory, but he also made sure they did not lose sight of the goal.

“The boys started signing autographs, people were asking them for their autographs,” Baca recalled with a slight chuckle. “And like I told them, I said, ‘Hey, you guys lose, you’re yesterday’s news so you got to keep focused.’”

The U.S. Championship ended up being a rematch between Northridge and Springfield. By chance, Baca had overheard Springfield’s coach talking on the phone about how confident he was they would advance to the world championship, proclaiming, “They’re gonna be throwing fastballs, but we can hit those.”

Baca took a mental note of those words and had his pitchers throw nothing but breaking balls the entire game. Springfield’s bats were silenced as they did not have a hit until the sixth inning.

In the final at-bat of the game, Baca heard the Springfield coach telling his batter “watch the curve.” He signaled for his pitcher to throw a fastball.

Strike one.

“Watch the curve,” the Springfield coach repeated as Baca called for another fastball.

Strike two.

“Watch the curve.” Another fastball.

Strike three.

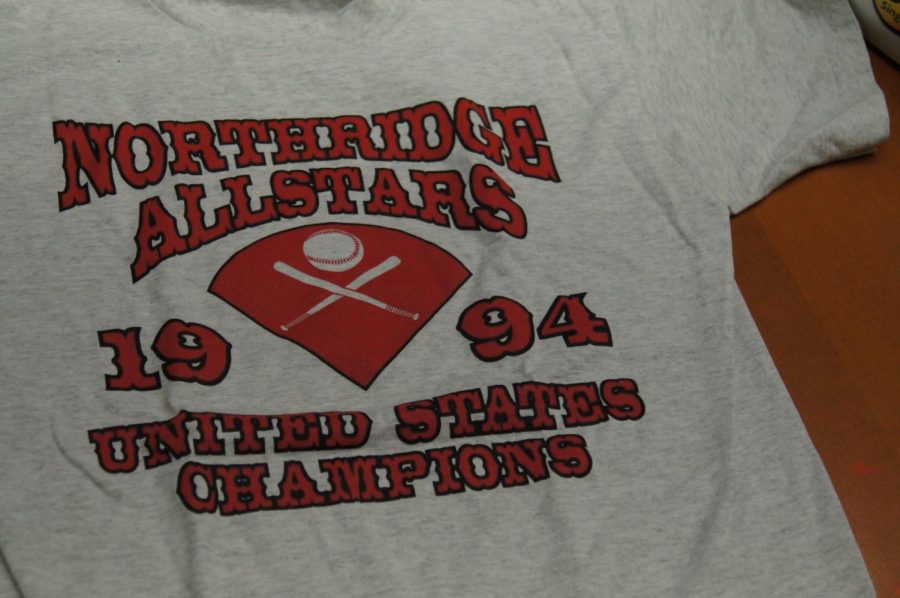

The Northridge All-Stars were the 1994 U.S. champions, shutting out Springfield for the second game in a row, 3-0 to advance to the Little League World Series Championship. Their attention now turned to Venezuela as even more attention had turned to the earthquake kids.

“Initially, I kept thinking, ‘This team is really good, why do they keep talking about the earthquake?’” Baca said. “But then as time went on, I started thinking these guys were so comfortable out there playing baseball. (The earthquake) was so traumatic that it probably did contribute a lot to going out there, playing, and forgetting about it.”

Just eight months prior, the team’s world was turned upside down. Many of them had to leave their hometown after their home was destroyed. If they weren’t thinking about the earthquake while they were on a national or worldwide stage, their community back home was definitely thinking of them.

“I was just a Northridge resident at the time,” said Audrey Ritter, current president of Northridge City Little League. “I didn’t know anybody on the team, wasn’t involved in the league, but it was a very exciting time for the community. I do remember that, not just the earthquake, just the fact that they went and they came back as the (U.S.) champs was phenomenal.”

The earthquake kids narrowly lost the championship to Venezuela, 3-4. Despite a noticeable size difference between teams and facing a pitcher that threw over 70 mph (equivalent to 100 mph in regards to 12-year-olds), Northridge was still able to make the game interesting. They returned home with their heads held high, knowing they made their mark on people watching.

“To me, they were like rock stars,” Ritter said. “I know all of our coaches and managers are just in awe of what they did because our coaches and managers, they have their own kids playing. And this is their dream, the Little League World Series.”

There was no shortage of love shown to the team after returning home. From trips to Disneyland, to having a parade thrown on Devonshire and Reseda and a street sign put up in their honor, to meeting then-Los Angeles mayor Richard Riordan, to meeting Presidents Bill Clinton and Ronald Reagan, to making an instructional video for other little league teams, to even having a role in the film “Three Wishes” alongside Patrick Swayze and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, the earthquake kids kept up with their rock star status.

It has been 25 years since that little league team from Northridge took the world by storm, and though they are now well into adulthood, the earthquake kids have been immortalized for how they rallied the community together and gave them something to cheer for in a year that was filled with so much adversity.

Although it happens less often now, Baca, now 74 years old, still gets recognized by people in the community from time to time.

“It used to be, walking down the street and somebody would come, ‘Hey! You coached that little league team,’ because it was so much on TV,” Baca, said. “The mailman would see me, ‘Hey, you guys should’ve won the game.’ And now, probably about a month ago I was at a car show, and a guy says, ‘Hey, weren’t you a coach in 94?’ That’s weird how a guy would remember that long ago, you know? It’s 25 years man, it’s gone by fast.”