In an effort to support those affected by President Trump’s Muslim Ban, the Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies hosted a discussion panel Monday in the Oviatt Library.

Executive order 13769, known by many as the “Muslim Ban,” barred people from seven predominantly Muslim countries from entering the U.S. for 90 days and suspended the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program for 120 days. The countries impacted are Syria, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Somalia, Yemen, and Iraq, according to panelists.

Nayereh Tohidi, director of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, said the event was organized because it is a timely issue.

“We wanted to bring community experts so that they could speak directly to students,” Tohidi said. “This is a timely event that will hopefully address concerns and questions that students may have.”

The four panelists have different backgrounds but shared similar stories.

Nisrin Abdelrahman, Stanford University graduate student, is originally from Sudan and was one of the many people detained at John F. Kennedy International Airport.

“In the chaos that followed, I was detained, handcuffed, I was body searched including in my groin area and questioned extensively before being released,” Abdelrahman said.

She explained the order was vague and it allowed the officers to interpret it.

“In my case, it was up to the officer in charge to decide whether or not I’d be released,” Abdelrahman said. “The language of the order is quite vague which then leaves much up for the interpretation by the officers who have their own biases and prejudices.”

Abdelrahman said she landed at the airport about 20 minutes after immigration officers found out about the order.

“The officer who questioned me was apologetic, but he also said ‘we have to do this to keep America safe,’” Abdelrahman said. “In my head, I keep thinking safe for who? Who does and doesn’t have right to feel safe and secure?”

According to Abdelrahman, the order that many others were also detained under, although, currently suspended, legalized discrimination based on the assumption that people from those nations posed a threat to national security even after going through an intensive vetting process.

The panelists explained that the executive order is impacting students and forcing many to deal with fear and uncertainty in their everyday lives.

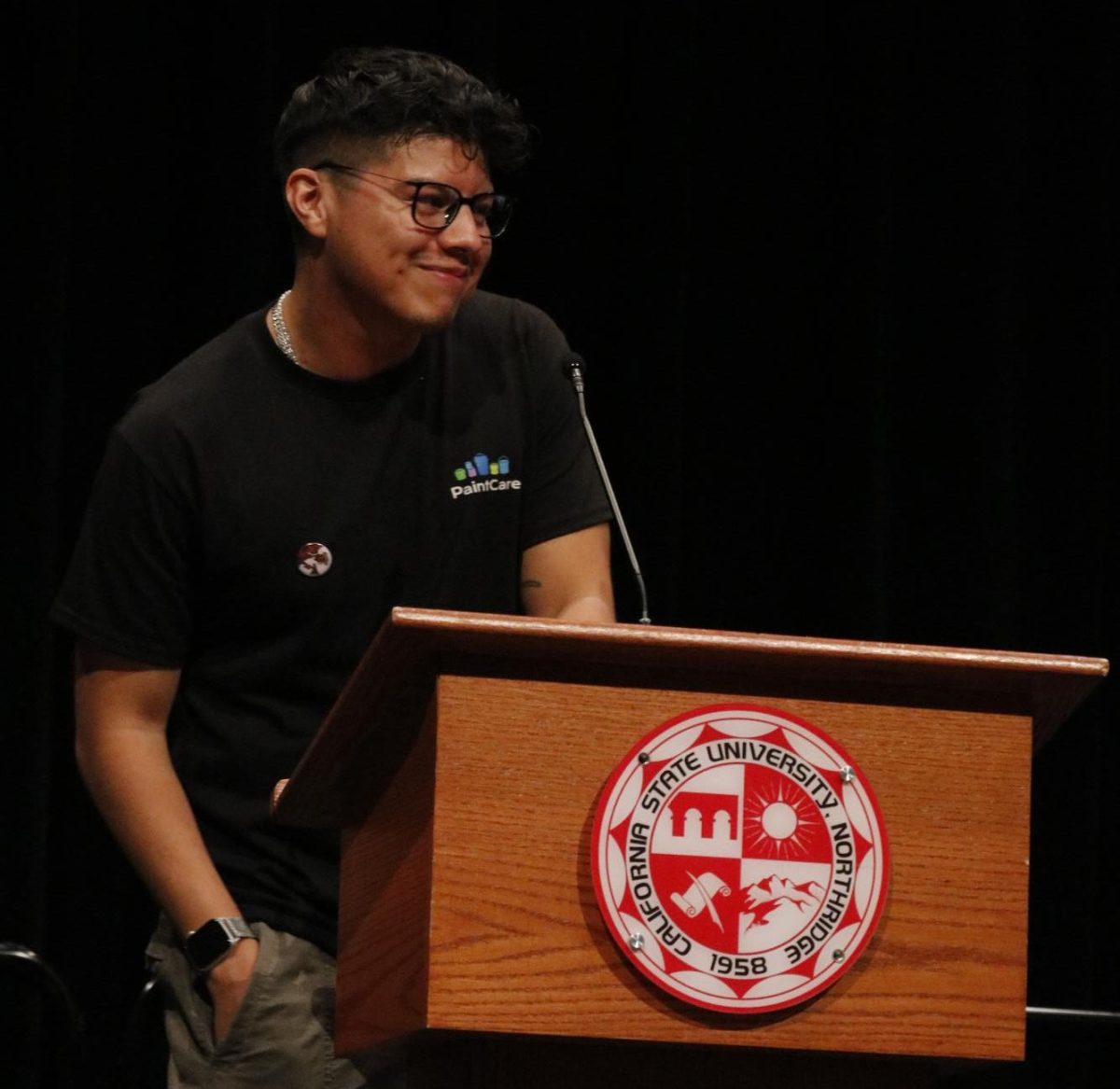

Obaida Albaroudi, president of Muslim Students Association (MSA) West, said he personally meets many Muslim students whose parents tell them not to protest.

“I know people whose parents tell them not to be active, loud, or political because they’re scared that they might bring attention and have the government focus in on them,” Albaroudi said. “The effect on college students is detrimental and not only for Muslims but the community at large.”

He also said the media portrays Muslims as terrorists with identifiers that could apply to many.

“I grew up as a Muslim that’s all I know,” Albaroudi said. “So when I’m hearing this as a college student who is already struggling with his identity, what am I supposed to think when I’m being told that my religion is pushing forward this idea of radicalization.”

Syed Hussaini, Outreach Coordinator for the Council of American Islamic Relations, said it was interesting to see that the order that was supposed to divide America achieved the opposite.

“We’re seeing collaborations between different communities,” Hussaini said. “The ban sparked chaos throughout airports across the U.S. and what was meant to divide is uniting us.”

Trump’s revised travel ban is expected to have the same basic policy outcome, but avoid confusion unlike the first one, according to panelists.

Eliana Kaya, CSUN alumni, became emotional while asking the panel a question.

“I stand strongly in solidarity with the Muslim community,” Kaya said. “As a Jewish person, I am not going to be silent when another community is being attacked.

Kaya said she became emotional because she can personally relate to being marginalized.

“This is a very important issue that we’ve seen before and we have to learn from history to progress,” Kaya said.