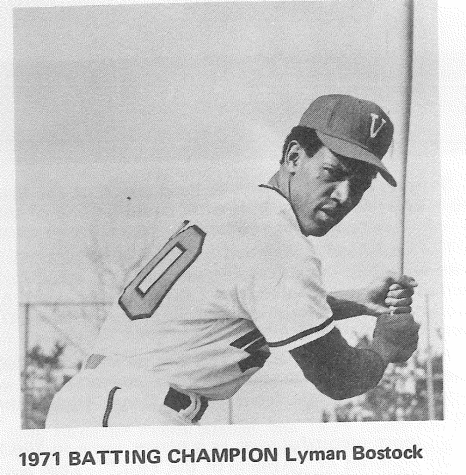

Lyman Bostock: Remembering a Matadors legend

Photo courtesy of CSUN Athletic Communications.

April 6, 2023

CSUN has produced a plethora of notable baseball players throughout its history and with the baseball season in full swing, it is a good time to reflect on some of these athletes. Lyman Bostock stands out as one of the most memorable baseball players the school has produced, both on and off the diamond.

Bostock was born on Nov. 22, 1950 in Birmingham, Alabama. Coming from a family already involved in major league baseball, Bostock’s future seemed destined to include the great American sport. According to ESPN, his father, Lyman Bostock Sr., played first base in the Negro Leagues in the early 1940s. Bostock Jr. had little use of his father’s knowledge, however. His parents separated, and his dad walked out on the family when Bostock was only two years old. At the age of eight, he and his mother relocated to Los Angeles.

The Alabama native played baseball at Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles before attending CSUN, or San Fernando Valley State College, as it was called then. According to ESPN, it was there that he met his future wife, Youvene Brooks. He did not play baseball during his first two years in college, instead focusing much of his time on student activism, according to CSUN Athletics.

Bostock became involved with the civil rights movement at CSUN, joining the Black Student Union in their student takeover of the Administration Building. According to CSUN Athletics, the protest saw him hold staff members hostage in an effort to convince the university to pass educational reforms meant to improve life for Black students on campus. CSUN Athletics reported that he was arrested and jailed for his participation in what was the “first mass felony conviction of student demonstrators in United States history.”

Bostock was selected by the St. Louis Cardinals directly following high school in 1968, according to CSUN Athletics. Deciding not to sign, he began playing under coach Bob Hiegert at CSUN in 1971. After his turbulent first years at the college, Bostock asked for another chance to play baseball, and was granted that opportunity after agreeing to a list of strict rules.

“What you saw is what you got from Lyman,” Hiegert told the Los Angeles Times in 2008. “There was nothing hidden about Lyman. He wore his heart on his sleeve.”

On one occasion, Bostock gave a bag of the CSUN team’s baseballs to school-aged children, Hiegert told the Los Angeles Daily News. “That’s pretty much the way the guy was,” the former coach said.

Bostock was revered by the Northridge community, often returning to play in the school’s alumni game, which, according to the Los Angeles Daily News, was later renamed the Lyman Bostock Memorial Game. Whenever the CSUN alum visited campus, coach Hiegert would cancel his practice and let Bostock run the show.

Before his death, Bostock wanted to start a scholarship at CSUN. According to the Los Angeles Daily News, he first touted the idea in 1978 during a conversation with Hiegert and California Angels announcer Dick Enberg. With some help, the two decided to honor Bostock’s wish after he passed away. The Lyman Bostock Scholarship Endowment is awarded annually to baseball prospects.

According to the Society for American Baseball Research, Bostock was an all-conference player in the California Collegiate Athletic Association during both of his seasons as a Matador. As a junior and a senior, he earned .289 and .344 batting averages, respectively, according to CSUN Athletics. In 1972, he led the Matadors to a second-place finish at the Division II College World Series. Drafted by the Minnesota Twins 596th overall in the 26th round of the 1972 amateur draft, he left school 15 credits short of his bachelor’s degree, as reported by ESPN.

For more than three years, he bounced between different minor league teams associated with the Minnesota Twins. Finally, in 1975, he received a call from the majors after hitting .391 in 22 games and 92 at-bats.

In his first MLB start on Apr. 8, Bostock went 1-for-4 but earned two walks and scored three runs in an 11-4 victory over the Texas Rangers. He finished the season with a .282 batting average in 98 games.

At the conclusion of the 1977 season, Bostock had the second highest batting average in the league, and became a free agent. During the offseason, the California Angels approached him with a five-year deal worth $2.3 million, according to SABR. Bostock was headed back to Southern California. Tragically, he never finished another season.

His character shined brightly during his final season when, according to the LA Times, he proposed to give his month of April’s salary back to the Angels because of a poor performance at the plate. He only managed a .147 batting average, and felt undeserving of the money. According to the LA Times, the Angels didn’t accept the offer, so Bostock instead donated it to charity.

On Sept. 23, 1978, Bostock was shot and killed following a game against the Chicago White Sox, SABR reported. According to The Sentinel Echo, he and his uncle were visiting Joan Hawkins, a woman he tutored when she was a teenager. Her sister, Barbara Smith, was also present, and at the end of the night, Bostock’s uncle agreed to give Smith a ride. In another car, Smith’s husband, Leonard Smith, pulled up next to them at a stop sign and shot Bostock in the temple. According to The Sentinel Echo, Smith later confessed that his wife was the intended target. Bostock’s grave is located at the Inglewood Park Cemetery in Inglewood.